Recent Articles

-

The Alphabet of Light, #17, by Kirsten Rian (Chris McCaw)

-

Alphabet of Light, #16, by Kirsten Rian (Robert Burley)

-

'Eyes Without a Face' Recent Works by Noel Rodo-Vankeulen

-

Jaime Lowe Interviews Theron Humphrey

-

An Interview with Darek Fortas

Categories

- #SANDY

- 2016

- 27th International Festival of Photojournalism

- Aaron Vincent Ekraim

- Africa

- AIPAD

- Almond Garden

- American Photo

- Anna Beeke

- Aperture

- Art Desks

- Artist Events

- Artist talk

- Award

- Awards

- Barmaid

- Barney Kulok

- Behold

- Best of 2015

- Book Launch

- Book release party

- book signing

- Book signings

- Book-signing

- Bryan Schutmaat

- Call for applicants

- call for entries

- Cara Phillips

- CDS

- Chicago

- ClampArt

- Closing Exhibition

- Competition

- Conservation photography

- Contests

- Cowgirl

- Critical Mass

- Cyril Christo

- Daily Mail

- Daylight

- Daylight Books

- Daylight Digital

- Daylight Digital Feature

- Daylight Photo Awards

- Daylight Project Space

- dj spooky

- Documentary Photo

- DPA

- Dread and Dreams

- E. Brady Robinson

- Eirik Johnson

- Elaine Mayes

- Elinor Carucci

- Events

- Every Breath We Drew

- exhibit

- Exhibition

- Exhibitions

- Fall 2015 Pre-launch

- Festivals

- Film Screening

- Film screenings

- Fine Art

- Flanders Gallery

- Fotobook Festival Kassel

- Françoise Callier

- From Darkroom to Daylight

- Frontline Club

- Gabriela Maj

- Gays in the Military

- george lawson gallery

- GuatePhoto

- Guatephoto Festival

- Hariban Award

- Harvey Wang

- hochbaum

- Home Sweet Home

- Huffington Post

- Hurricane Sandy

- Interview

- J.T. Leonard

- J.W. Fisher

- Janet Mason

- Jess Dugan

- Jesse Burke

- John Arsenault

- Jon Cohen

- Jon Feinstein

- Katrin Koenning

- Kuala Lumpur Photo Awards

- Kwerfeldein

- L'Oeil de la Photographie

- LA

- Landmark

- Leica Gallery

- Lenscratch

- LensCulture

- Library Journal

- Lili Holzer-Glier

- Lori Vrba

- Lucas Blalock

- Malcolm Linton

- Marie Wilkinson

- Mariette Pathy Allen

- Michael Itkoff

- Month of Photography Los Angeles

- Mother

- Multimedia

- Nancy Davidson

- New York

- New York City

- News

- NYC

- ONWARD

- Opening

- Opportunities

- Ornithological Photographs

- Out

- Party

- Philadelphia

- Photo Book

- Photo Booth

- photo-book publishing

- PhotoAlliance

- Photobooks

- Photography

- Photography Festival

- photolucida

- Poland

- portal

- Pre-Launch

- Press

- Prize

- PSPF

- Public Program

- Raleigh

- Rayko Photo Center

- Recently

- Rencontres De Bamako

- Reviews

- Robert Shults

- Rockabye

- Rubi Lebovitch

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Seeing Things Apart

- SF Cameraworks

- silver screen

- Slate

- slideluck

- Sociological Record

- Soho House

- spring 15

- Spring 2016

- Stephen Daiter Gallery

- Sylvania

- Talk

- Tama Hochbaum

- The Guardian

- The Moth Wing Diaries

- The New Yorker

- The Photo Review

- The Solas Prize

- The Superlative Light

- The Telegraph

- TIME

- Timothy Briner

- Todd Forsgren

- Tomorrow Is A Long Time

- TransCuba

- Upcoming events

- USA Today

- VICE

- Vincent Cianni

- Visa Pour L'Image

- Vogue

- We Were Here

- Wild & Precious

- Wired

- Workshop

- Zalmai

- Zofia Rydet

News

The Alphabet of Light, #17, by Kirsten Rian (Chris McCaw)

Posted by Daylight Books on

Photograph by Chris McCaw

What the Sun Says

In 1605 German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler presented his first ‘law’ of orbits, stating that all planets move in elliptical orbits, with the sun as center focus. Earning the title, founder of modern optics, Kepler was also the first to consider picture-making with the pinhole camera. But it was his theories on the sun’s rotation about its axis (derived without the use of a telescope) that revolutionized the consideration of time and space and our relative place within the sky.

“Discover the force of the heavens O Men: once recognised it can be put to use,” Kepler wrote in De Fundamentis, published in 1601.

And put to use, photographer Chris McCaw does, by looking up, looking outward, and 400 years following Kepler’s thoughts, catching the angle of the earth’s tilt and degree trajectory along its path, depicting that line of light in a literal way, and partnering with the sun to burn the evidence onto paper.

Using his own constructed view cameras (sometimes as large as 30 x 40 inches, built around garden wagons and converted wheelchairs, and outfitted with military aerial reconnaissance camera optics), McCaw solarizes directly onto silver gelatin paper for extended exposures. The sun at times cuts straight through, scorching the prints at its most intense spots.

The result of years of diligent experimenting and fine-tuning of process and materials, the Sunburn project had accidental beginnings.

“In 2003 an all night exposure of the stars made during a camping trip was lost due to the effects of whiskey. Unable to wake up to close the shutter before sunrise, all the information of the night’s exposure was destroyed. The intense light of the rising sun was so focused and powerful that it physically changed the film, creating a new way for me to think about photography.

In this process the sun burns its path onto the light sensitive negative. After hours of exposure, the sky, as a result of the extremely intense light exposure, reacts in an effect called solarization- a natural reversal of tonality through over exposure. The resulting negative literally has a burnt hole in it with the landscape in complete reversal. The subject of the photograph (the sun) has transcended the idea that a photograph is simple a representation of reality, and has physically come through the lens and put it’s hand onto the final piece. This is a process of creation and destruction, all happening within the the camera,” McCaw writes.

We discuss if this project is in part a statement on the photography industry and the medium itself, a look at where it’s been, where it’s heading. “I wouldn't say it is a study on the industry, but I would say it proves there is more potential beyond our traditional ideas of the medium,” McCaw says.

“I enjoy physically working with the medium,” he continues. “All forms of capturing and printing an image are valid. I just prefer to have more of a hand in the process.”

If a book can be soulful in its rendering of subject, then Gordon Stettinius and his team at Candela Books publishing did just that. Gorgeously and thoughtfully executed, McCaw’s new book, Sunburn, is an object unto itself. Gate folds, double page spreads, and facing images all combine with the quiet stature of single images anchoring a spread, composed in a sequence that feels paced and rendered in symphonic movements.

As the tone of the book reflects, and the imagery evidences, work that lingers, the projects that resonate, illuminate as much to the artist as to the viewer. “I have learned that life goes by fast and we tend to experience it in short bursts,” McCaw shares. “Before this project, an hour long exposure would have felt like forever. My sense of time has completely shifted. Now sitting in one spot from sunrise to sunset, a full day seems like a lunch break. It really does. And while I am there I watch a location be experienced by various people over a day. It is amazing how fast and furious we move through our days.”

These images measure the sun’s explanation for light and dark, as revealed in the axis points and angles of intersection between shadows and brightness. In the book’s afterword, entitled “Notes on Watching Shadows Move,” McCaw writes, “During all this, I’ve become attuned to the reality that we’re all running around on a spinning marble orbiting a fiery ball. It’s that simple and amazing, but we rarely give ourselves time to ponder this.”

Johannes Kepler composed an epitaph for himself a few months before he died that reads: I used to measure the heavens, now I measure the shadows of Earth. Although my mind was heaven-bound, the shadow of my body lies here.

Of McCaw’s inspired Sunburn project, photography great Linda Connor perhaps says it best, “It may have started that bright morning in the desert with happenstance, but every work that has followed has been the result of intelligence, diligence, patience, science, and an artistic heart, open to beauty and wonder. Chris McCaw has turned photography around and shown us the world anew.”

To learn more about the book or place an order, visit: https://candelabooks.com/our-books/sunburn/

Daylight was the first publisher to feature McCaw’s work. See for yourself in Issue #5.

To learn more about McCaw and his projects, visit: http://www.chrismccaw.com/Home.html

A show of McCaw's work opens at Yossi Milo Gallery on November 29. For more info see: http://www.yossimilo.com/exhibitions/2012-11-chris_mccaw/

Alphabet of Light, #16, by Kirsten Rian (Robert Burley)

Posted by Daylight Books on

Photograph by Robert Burley

Employee Darkroom Area, Building 9, Kodak Canada, Toronto 2009

Interplay

Ironically enough, it was way back in 1951, an era clearly immersed in film, that Berenice Abbott wrote, “In fact, the photographic medium is standing at its own crossroads of history, possibly at the end of its first major cycle. A decision as to which direction it shall take is necessary, and a new chapter in photography is being made...” She was referring of course to photography’s place amidst the rise of multiple visual mediums--television, film, magazines. But the points she addresses in her iconic “Photography at the Crossroads” article are as relevant as ever, today.

It’s not that Canadian photographer, Robert Burley, is any stranger to the digital realm of photography’s new voice. He recently completed an exhibition of digital prints from a comprehensive architectural survey project of Toronto’s first synagogues that also included a virtual exhibition in collaboration with the Ontario Jewish Archives. He has also manipulated imagery on a digital platform for other work. But his new book, “Disappearance of Darkness,” is an homage, a direct look, at the demise of the very thing that used to hold pictures: film.

“Over the last decade, the medium of photography, my life’s work, has been utterly transformed, radically and irrevocably...It is now clear that the dark, chemical, and physical photography that I knew in the first part of my life, will not survive into the next. My own experience with making photographs, one that involved not only seeing, but also touching, smelling, and navigating my way around dark rooms with trays of chemical baths and “safe” lights is all but gone,” Burley states.

“To chart a course, one must have a direction,” Abbott continued in her essay. The direction is clear, photography is, as Burley reflects in his book’s subtitle, ‘at the end of an analog era.’

The book is comprehensive, addressing many angles of the photography world as it once was--interiors of darkrooms, exteriors of photo studios, a suite of images documenting the demolition of the Kodak-Pathé building GL in Chalon-sur-Saône, parts of the Eastman Kodak campus in Rochester, New York, sites of significance to the industry such as Afga in Belgium, abandoned Polaroid buildings in Waltham, Massachusetts, a rusted out Ilford Paper cargo container outside the paper finishing building of the company headquarters in the UK--all iconic names, representing a once flourishing industry.

And staying conceptually consistent, Burley produced all the images in the book using traditional methods. The photographs were created with a Toyo 45A Field Camera using a 90mm Sinar Sinaron, f/4.5 lens, a 180mm Horseman Topcor, f/5.6 lens, and a 210mm Sinar Sinaron S, f/5.6 lens. Three different types of chromogenic negative 4" x 5" sheet film were used to make the images: Kodak Portra NC 160, Kodak Portra VC 160, and Fujicolor NPL 160. Polaroid Type 55 black and white positive/negative film was used as a test fim to determine proper exposure and focus. At the end of the project in 2011, only Kodak Portra 160 (a newer version of the Portra NC 160 and VC 160 films) remained on the market.

The project as a whole prompts another layer of questions around the more intangible, but arguably most important, components of image-making. If the tools have changed--considerably and irreconcilably--does that mean the images have, or have to, as well? How directly is process linked to content? How does technology dovetail, affect, and influence the art and story of photograph?

Burley weighs in on this. “I believe the intention (heart and mind) are always most important and ultimately what we see in any artist’s work regardless of technology they used to create it. However, just to play devil’s advocate, let’s look at another artist living at the turn of the last century who lived through a time of remarkable change – Edward Steichen.

Which images were the ones that truly expressed his heart and mind – was it the paintings he did while living in Paris (we’ll never know because he destroyed them), was it those heavily manipulated gum-bichromate prints (The Pond recently sold for almost $3 million), perhaps it was those Autochromes he did with Stieglitz – or the fashion work he did for Conde-Naste – maybe even some the aerial photographs he made as an officer in the war (some of those are in the collection of the Metropolitan)?

My answer would be all of the above and I would bet that his experience and/or idea of what photography was changed many times throughout his life.”

In his introductory essay, Burley writes, “All photography is about loss.”

Indeed, each day is about loss, each step taken, each hand held, peels away at some aspect of self or past or hope. Loss is a concept holding negative implications, and often it should because often it’s sad. But the necessary distinction is that it doesn’t have to, all of the time, in its entirety. As with most things both ordinary and splendid, effect and consequence rest in the crux of complexity arising from call and response, from dark running into light. The edges are where the truth rests and where loss and gain blur. And perhaps that is where we are right now in this time of transition from analog to digital.

“Regardless of what technology used to make photographs (analog or digital) I believe the next generation will make different kinds of imagery,” Burley says. “Both are being redefined by each other. In the world of light-sensitive materials artists have been freed from photography’s role as a multi-faceted societal application – it is now purely an art form and it will continue to flourish as such. In the digital world, still images will continue to be combined, embedded mixed and mashed-up with other forms of media. They will retain a connection to our idea of photography but become something else.”

To view more of Burley’s work visit: http://www.robertburley.com/

'Eyes Without a Face' Recent Works by Noel Rodo-Vankeulen

Posted by Daylight Books on

"The title, which references the mechanized and often detached character of the image, reflects Rodo-Vankeulen's interest in the nature of pictures as a realm for visual, poetic and conceptual possibility."

Photography is a medium like no other. With a simple tool called the camera, a person is able to freeze a fraction of a moment in time, record it, and cherish that moment forever. However, despite this engaging motif, many photographs that we see in our daily lives today, have become mundane and normal, no longer representing the capture of the fleeting moment. By opening up new ways of seeing and new contextual spaces, Noel Rodo-Vankeulen reveals the sophisticated visual dynamic that is embedded in all images.

Noel Rodo-Vankeulen will be having a reception for his new exhibition 'Eyes Without a Face' presented by O' Born Contemporary on Friday, November 16th from 6-9PM.

Information:

http://campaign.r20.constantcontact.com/render?llr=bmlpogdab=001_3wh4u...

Jaime Lowe Interviews Theron Humphrey

Posted by Daylight Books on

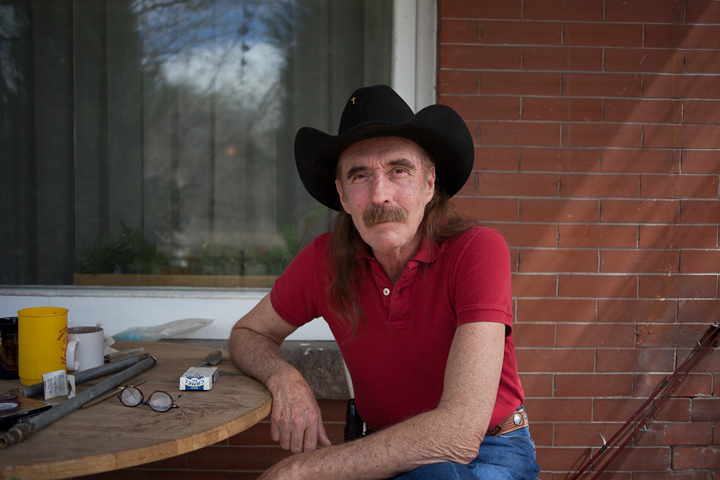

Have you ever heard a song, or read a book, or watched a movie that you wish you created? Well, to be honest, I wish I had come up with the premise behind Theron Humphrey’s This Wild Idea. In 2011, Humphrey set out on his goal: to meet and photograph one person a day for a year. He traversed 66,565 miles, and visited all 50 states. Not only did he photograph his subjects and the details of their lives, he gave each person an opportunity to tell his/her story through a recorded interview which he features alongside their portraits on thiswildidea.com. Humphrey’s earnest and classic storytelling approach, and compassionate, intimate photographs that span the entire country and its citizens have garnered international recognition and an impressive audience.

The other day, I had a chance to ask Theron a few questions about This Wild Idea, his coonhound Maddie, and the role the Internet has played in his work.

JL: So, first off: Where are you from?

TH: I was born and raised in coastal North Carolina. It’s the sort of place you’d still see tobacco growing. I spent my childhood on my grandparents' farm and the suburbs. I still like existing in that space between city ideals and country living.

JL: And when and how did you get into photography? (Was it during the age of film?) Where did you go to school?

TH: I went to undergrad in Eastern Tennessee, in the Appalachian Mountains at a small liberal arts college you’ve probably never heard of. I went to study computer science, but along the way I fell in love with photography. It’s easy to love photography, ya know? I like that it’s somewhere in between craft and science. Like most folks, I have fond memories of darkrooms and chemicals. But one thing that I remember about being in grad school is shooting with the Canon 20D. I remember feeling like the images were good.

JL: How did This Wild Idea come about?

TH: That’s a long story. I wish I could sit down with all the folks who are going to read this. I’m pretty sure I’m better at telling stories than writing them.

I have a long-winded version of the story, but 3 big things happened in my life that stirred me up to live a different story. Hopefully to live a life that looks funny to most of the world. I was burnt out on corporate life. My grandfather passed away. And I was broken hearted. Those all came together at the same time. I literally woke up one morning and said I was gonna go do something different, I wanted to create work that I could point at and say I loved.

JL: When did you start This Wild Idea and how many days were you on the road?

TH: I started August 1st, 2011 and finished August 1st, 2012. I was on the road for 365 days. Meeting folks everyday. I literally used my camera every single day. There was a lot of beauty in that. And discipline.

JL: And This Wild Idea was funded entirely by donations?

TH: Yep, it was. I raised $16,000 on Kickstarter. Sort of amazing, right? I’m grateful.

JL: You’ve been traveling with your adorable and super flexible coonhound Maddie, who is the subject of your book “Maddie On Things” which will be coming out in April 2013 under Chronicle Books. How is it traveling with her?

TH: When I first started this project some folks asked me how I’d travel and entire year with a dog. I was nervous. I don’t have kids yet, but I think this is a good way to explain it….I figure most folks are scared about how much their life will change when they have children. How nothing will be the same. They think about the sort of stuff they will have to sacrifice. But when their first child comes into the world they wouldn’t trade it for anything. It becomes they life they know and love.

Traveling with a dog is a tiny slice of that.

JL: What kind of gear are you shooting with?

TH: I shot This Wild Idea with a Canon 5D Mark II with a vintage Carl Zeiss 35mm f/2.8 and Zoom H4N recorder.

Images of Maddie were shot on my iPhone 4 and these days an iPhone 5.

JL: So all the images of Maddie in "Maddie on Things" were taken with an iPhone?

TH: Yep! Mobile photography is a big conversation, but I honestly felt a lot of whimsy using my iPhone this past year.

JL: How do you pick/find your subjects for This Wild Idea?

TH: About half the folks I photographed I just walked up to and said hi. I don’t know about ya’ll, but I have to swallow my gut every time I do that. I love it, but it also makes me nervous. It’s hard, at least for me. I didn’t want to travel America and just be a voyeur. I wanted to engage. I wanted to put myself out there. I found that’s how to you grow, you know, as a person and image maker.

The other half of the folks I photograph were people who ‘Change my route’. I wanted to have a project where everyone could follow along, to watch it grow, not just view it afterwards. Some of the best days were when someone changed my route go to meet their grandparents. I loved those days.

JL: One of my favorite parts about This Wild Idea is the humanitarian aspect – each person you photographed had the opportunity to tell his/her own story through their own words in their recorded interview. You literally gave a voice to these people. Was this one of your goals for this project?

TH: I flew in from Idaho to visit my grandfather in North Carolina in the winter of 2010. I never gave much thought to photography being a platform for story telling. Does that sound weird? I always looked at photography as a way to express some sort of intellectual idea. But there was a shift that winter. Point my camera towards my grandfather was this literal act of me loving him.

When I got back to Idaho he passed away. In a heartbeat those images became more valuable. You couldn’t go talk to him. You couldn’t take his portrait. It was a funny feeling because I loved him and I had this body of work to show my kids one day, but the world didn’t even know he existed. Does that make sense? Sort of hard to explain.

I wanted to go into the world and meet folks like my grandfather. Folks like my mom. I wanted to meet them, to celebrate their lives, their story. All of these everyday memories that make up a life.

JL: And everyone’s favorite question: do you have any influences/heroes, and if so, who are they?

TH: I bet most of mine are similar to ya’lls. Robert Frank, Stephen Shore, Steinbeck. I dig the fellas who traveled America.

But more personally the project was influenced by what I love in life, what I found valuable. Sitting around with folks, learning to love my neighbor, and hearing stories.

JL: Do you have any notable on-the-road funny stories/horror stories/anecdotes?

TH: I bet I visited over 200 McDonald's. Over time, I found a lot of comfort and ritual in stopping at ‘em. Not so much to eat there, but they all have Wi-Fi these days and decent coffee for $1. The other awesome things about McDonald's, regardless of which state you’re in, there are always World War II vets hanging out there in the morning.

JL: And do you have any more plans for This Wild Idea? (A book, an exhibit?)

TH: I’m content with This Wild Idea existing as a web project. It’s free to access. I like that there isn’t a cost for entry.

But I did apply for an artist residency at Light Work in Syracuse, NY to turn the project into a gallery exhibition and develop a new interactive audio experience. That would be a nice capstone. Maybe we can convince them to let me?

JL: You have quite the following on Instagram with 114K followers, and This Wild Idea is exhibited solely on the Internet (right now). Do you have any remarks or thoughts on the role of the Internet/social networking and photography today? How has it benefited you, and has it ever worked to your detriment?

TH: This is the biggest audience I’ve ever had. Most days it blows my mind. I have 114,000+ Instagram followers, 35,000+ Tumblr followers and 7,500 Facebook fans just for This Wild Idea. It’s amazing and troublesome and daunting. It’s all of those things.

Ultimately I’m grateful. It’s such a blessing to be able to share what I love with such a large audience. Well, a large audience for someone like me. These days I’m just trying to remember that it’s about the work we create, the story we leave behind, not the platform we share through. Intsagram and Twitter and Tumblr will come and go, but if we love each other in our communities. You know, your literal next door neighbor, then we’ll be successful.

JL: Are there any other projects coming up that we should know about?

TH: In the spring I’m hitting the road again to do a 48-state book tour with Maddie! It’s going just be a ton of fun. Literally. I’m looking forward to traveling again, but with more whimsy.

JL: And finally, what advice would you give young people (photographers) today?

TH: I woke up one morning and realized I’d just have to make way less money in life if I wanted to wake up each day and take images of what I loved. I found peace in it. You know, not making much money. It’s hard to explain how precious that is until you go through photo school and end up shooting product photography.

More of Theron's work can be found here:

With the exception of the first image of Theron by Cory Staudacher, all photos included by Theron Humphrey.

An Interview with Darek Fortas

Posted by Daylight Books on

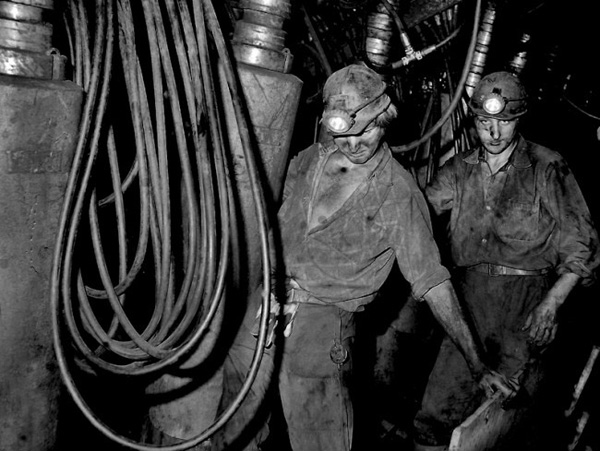

Photographer Darek Fortas’ most recent project, Coal Story, is a personal response to the history and aftermath of the Solidarity movement in Poland. The movement — led by human-rights activist Lech Wałęsa — was paramount for Poland’s labor parties and trade unions and their rise to independence throughout the 1980s. In approaching the subject photographically, Mr. Fortas — who is now based in Ireland, but originally from Poland — culled images from photographic archives dating back to the 1960s. Using these historic images of Polish coal miners in addition to his own large-format photographs of the present day, Fortas’ Coal Story takes place before, during, and after the uprising of Solidarity. Read a recent interview about the project between Fortas and Daylight below.

---

Interview by Trent Davis Bailey

Photographs by Darek Fortas

Daylight: As a Polish image-maker living abroad, how did you realize your Coal Story project?

Darek Fortas: I think it is quite common that places we are originally from gain much more significance when we move somewhere else. After spending more than seven years in Ireland, I realized the importance of going back and making a photographic body of work about Silesian identity and how the mining industry manifests itself thought the photographic lens. At the same time, I’m interested in how photography touches on the communist resistance movement and the conflict between the individual and the state.

D: For your project, you acted as both a photographer and a researcher. Can you explain your process that led to you discovering the archival photographs?

DF: Each coalmine I worked in had an archive section. In most cases it is a room — roughly 25 square meters in size — dedicated to preserving the most important artifacts from the mine’s past. When I went there for the first time, most of the stuff was covered with dust. It was quite a surreal experience.

Such communist propaganda was pretty much about the celebration of so-called “progress,” so all of the new industrial developments and celebrations inside the mine had to be well documented. They were aware that images convey power and wanted to show coal miners as a very happy, fulfilled social class.

I also came across another source of archival material by accident. I was finishing shooting one day and I met a guy who was sticking a sewing machine repair service ad on a noticeboard. I decided to talk to him and he turned out to know a photographer named Joseph Zak, who used to document everyday life in Silesia. This is how I obtained images from outside of the mines — taken by Mr. Zak — which depict strikes and protests.

D: If these sorts of pictures had been discovered prior to the movements’ succession, would there have been repercussions?

DF: You could certainly face imprisonment. There are many cases I heard of where people were disappearing in unknown circumstances because they were openly manifesting themselves against the Communist Party.

For the majority of people, communism was about standing in line with others. If you stepped out of the line by trying to do different things than the others, you were automatically putting yourself at risk.

D: Out of all of the photographs you found, which surprised you the most?

DF: The photographs I found in a museum beside the Wujek coal mine. The 35mm film was shot on December 16, 1981, then processed a few days after. Because the photographer who took these images was afraid of militia and the secret service, he decided to bury the processed film under the ground in a safe place. It was not until 1991 that the first prints were made from it. I think this works as a great illustration of what life under communism was like if you were openly against the regime. It is a miracle that the guys from the museum could recover some of the frames.

D: Many of the images you found show an underground society—both literally and politically. What were the factors that influenced the making of the photographs from the mines and how does this relate with your own photographic approach?

DF: Well, why do we make images? The act of making the images in the 1980s confirmed the importance of those events to these people.

Images cannot function in a vacuum, without an audience. This is where their power comes from, but at the same time, much risk is attached. Interestingly, quite a big number of archival images I appropriated for this proejct, through a depiction of ‘dissensual activities’ around the mines, played a crucial role in disrupting the monopoly of power distribution of the communist state.

My contemporary photography in the project examines the conditions of the labor inside the mines, articulates disillusion by the new order, and contests the values of capitalism. Ultimately, Coal Story is about providing a visual form, or anesthetization for the political capacity of the masses, representing the socio-political transformation in Poland and other Eastern and Central European countries.

D: Going back to the photos that you found. What is happening is this picture?

DF: This picture titled "Archival Image VI (National Miners’ Day Celebration, 1986)" was appropriated from one of the mine’s archives. It was taken during Miners’ Day (also known as St. Barbara’s Day), which is celebrated on the fourth of December each year.

A miner’s profession in Silesia was and still is well respected, and this is a big day for most of the families. This picture shows a group of miners at one of the games pulling the line. Wearing facemasks is a form of punishment from others at the party. This suggests that all of the people in this picture are heavily intoxicated. Each mask gives a signal to other colleagues at the party that they are not supposed to drink anymore until they sober up. It also obscures each person’s identity should they misbehave. Wearing masks is still practiced during St Barbara’s Day.

D: Did the historical photographs you found change what you previously had known about the Solidarity movement?

DF: Working with archive did mean I could consult many different people that provided me with many different accounts, which eventually made me disillusioned about the movement, especially after the political transformation of 1989.

I think if you work closely with in topic like that, at some stage, you become aware that what is taught in schools — or can be accessed in history books — about the movement is oversimplified. I have to add here that photography has one extra power: people always bring their own agenda to the images. This plays a huge role in deciphering the medium.

Solidarity, which used to be the liberation mass movement, turned into one of the official trade unions and got very corrupted after 1989. The fact is, it played a very important role in mobilizing the masses in communist Poland and brought people hope for a social betterment. It was very important for me to imbed this knowledge into my images when I was making the project.

D: Did these archival photographs change your own photographic approach to what you were looking for when photographing the coalmine?

DF: They significantly enriched the project. For me, looking at and editing the archive was the most diversified visual journey I have had to date. I work very slowly while photographing — things are carefully considered and arranged — while these archive pictures are more “off-the-hip.”

Also, I did not want to fall into a photojournalistic aesthetic routine that is quite rigid. I believe if you are an image-maker it is extremely important to constantly push the limits of what is visible and thinkable, otherwise everything is going to be homogenous. And if it is, why bother to make images?

D: This picture raises a lot of questions. What’s the story behind it?

DF: This image shows a miners’ changing room. When this particular coalmine was opened in 1964, they invented a very efficient air conditioning system that also was perfect for drying clothes overnight, so miners could wear fresh clothes the next working day.

Each miner has a key to a lock. In the large print of this image, you can see these on the left and right. Each mine has around three thousand similar locks, which would make up around twenty rooms like this one. When the miners finish work they open the lock, bring their clothes and other belongings with them, go for a shower, get changed, hang their fresh clothes, pull them up on the chain and leave it overnight until the following day.

This system has not been changed for nearly fifty years despite the fact that coal companies in the region are extremely wealthy from producing high quality coal for steel production and export worldwide.

D: What is life like for a coalminer in present-day Poland as compared to life before Solidarity?

DF: Quite different, but some aspects have remained unchanged. Of course, labor conditions have improved significantly. Everything is regularly monitored to maintain the very best safety inside the mines.

I learned that the tax rate in the 1960s was 95 percent. This meant that even the smallest rise in food prices profoundly affected most of state’s citizens. Also, if you were a miner you had only one day off per month. The main reason for making Coal Story is the fact that in 1981 prices of basic food products were raised to such a high level that it was unaffordable for the working class; therefore, they went on strike. The core of the communist doctrine had a focus on developing the military potential of the USSR and the coalmines from Silesia were used for their steel production. Mining had become the most important branch of the economy. Having control over coalmines became crucial, and miners who refused to work simply had the power to paralyze the entire economy.

What remains the same today are the miners’ celebrations on the fourth of December.

D: Obviously access played a huge role in both finding the archived images as well as gaining entry to the mine. What would you say was your largest obstacle in the project?

DF: Negotiating the access to such a huge industrial complex proved difficult. I had to wait five months for my proposal to be granted.

When making images inside the mines I always had a supervisor assigned to me. We had quite an interesting relationship. At the very beginning of the project each supervisor felt obliged to tell me which part of the mine would make an interesting story. They were walking me around the mines, pointing things out that should be photographed, which were based on what other photographers had found interesting in the past. I had to maintain a friendly relationship with them and I could not just say I am not interested in being an advocate for their way of seeing. Sometimes, to remain friendly, I was pretending I was making images. When they heard sound of the shutter (with film slides or my camera’s back closed) they were instantly convinced I captured what they wanted. Generally after twenty to thirty minutes they let everything go and I was free to photograph what I wanted.

Also, making images of miners straight after they finished their shift proved quite difficult. Silesian people are generally notorious for their attitude. I waited for some of the opportunities to make portraits for nearly ten months.

---

For more information about Darek and his work, visit: http://www.darekfortas.com