Photographer Darek Fortas’ most recent project, Coal Story, is a personal response to the history and aftermath of the Solidarity movement in Poland. The movement — led by human-rights activist Lech Wałęsa — was paramount for Poland’s labor parties and trade unions and their rise to independence throughout the 1980s. In approaching the subject photographically, Mr. Fortas — who is now based in Ireland, but originally from Poland — culled images from photographic archives dating back to the 1960s. Using these historic images of Polish coal miners in addition to his own large-format photographs of the present day, Fortas’ Coal Story takes place before, during, and after the uprising of Solidarity. Read a recent interview about the project between Fortas and Daylight below.

---

Interview by Trent Davis Bailey

Photographs by Darek Fortas

Daylight: As a Polish image-maker living abroad, how did you realize your Coal Story project?

Darek Fortas: I think it is quite common that places we are originally from gain much more significance when we move somewhere else. After spending more than seven years in Ireland, I realized the importance of going back and making a photographic body of work about Silesian identity and how the mining industry manifests itself thought the photographic lens. At the same time, I’m interested in how photography touches on the communist resistance movement and the conflict between the individual and the state.

D: For your project, you acted as both a photographer and a researcher. Can you explain your process that led to you discovering the archival photographs?

DF: Each coalmine I worked in had an archive section. In most cases it is a room — roughly 25 square meters in size — dedicated to preserving the most important artifacts from the mine’s past. When I went there for the first time, most of the stuff was covered with dust. It was quite a surreal experience.

Such communist propaganda was pretty much about the celebration of so-called “progress,” so all of the new industrial developments and celebrations inside the mine had to be well documented. They were aware that images convey power and wanted to show coal miners as a very happy, fulfilled social class.

I also came across another source of archival material by accident. I was finishing shooting one day and I met a guy who was sticking a sewing machine repair service ad on a noticeboard. I decided to talk to him and he turned out to know a photographer named Joseph Zak, who used to document everyday life in Silesia. This is how I obtained images from outside of the mines — taken by Mr. Zak — which depict strikes and protests.

D: If these sorts of pictures had been discovered prior to the movements’ succession, would there have been repercussions?

DF: You could certainly face imprisonment. There are many cases I heard of where people were disappearing in unknown circumstances because they were openly manifesting themselves against the Communist Party.

For the majority of people, communism was about standing in line with others. If you stepped out of the line by trying to do different things than the others, you were automatically putting yourself at risk.

D: Out of all of the photographs you found, which surprised you the most?

DF: The photographs I found in a museum beside the Wujek coal mine. The 35mm film was shot on December 16, 1981, then processed a few days after. Because the photographer who took these images was afraid of militia and the secret service, he decided to bury the processed film under the ground in a safe place. It was not until 1991 that the first prints were made from it. I think this works as a great illustration of what life under communism was like if you were openly against the regime. It is a miracle that the guys from the museum could recover some of the frames.

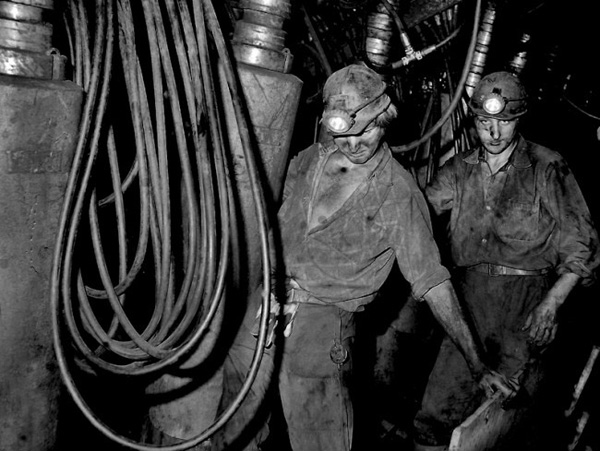

D: Many of the images you found show an underground society—both literally and politically. What were the factors that influenced the making of the photographs from the mines and how does this relate with your own photographic approach?

DF: Well, why do we make images? The act of making the images in the 1980s confirmed the importance of those events to these people.

Images cannot function in a vacuum, without an audience. This is where their power comes from, but at the same time, much risk is attached. Interestingly, quite a big number of archival images I appropriated for this proejct, through a depiction of ‘dissensual activities’ around the mines, played a crucial role in disrupting the monopoly of power distribution of the communist state.

My contemporary photography in the project examines the conditions of the labor inside the mines, articulates disillusion by the new order, and contests the values of capitalism. Ultimately, Coal Story is about providing a visual form, or anesthetization for the political capacity of the masses, representing the socio-political transformation in Poland and other Eastern and Central European countries.

D: Going back to the photos that you found. What is happening is this picture?

DF: This picture titled "Archival Image VI (National Miners’ Day Celebration, 1986)" was appropriated from one of the mine’s archives. It was taken during Miners’ Day (also known as St. Barbara’s Day), which is celebrated on the fourth of December each year.

A miner’s profession in Silesia was and still is well respected, and this is a big day for most of the families. This picture shows a group of miners at one of the games pulling the line. Wearing facemasks is a form of punishment from others at the party. This suggests that all of the people in this picture are heavily intoxicated. Each mask gives a signal to other colleagues at the party that they are not supposed to drink anymore until they sober up. It also obscures each person’s identity should they misbehave. Wearing masks is still practiced during St Barbara’s Day.

D: Did the historical photographs you found change what you previously had known about the Solidarity movement?

DF: Working with archive did mean I could consult many different people that provided me with many different accounts, which eventually made me disillusioned about the movement, especially after the political transformation of 1989.

I think if you work closely with in topic like that, at some stage, you become aware that what is taught in schools — or can be accessed in history books — about the movement is oversimplified. I have to add here that photography has one extra power: people always bring their own agenda to the images. This plays a huge role in deciphering the medium.

Solidarity, which used to be the liberation mass movement, turned into one of the official trade unions and got very corrupted after 1989. The fact is, it played a very important role in mobilizing the masses in communist Poland and brought people hope for a social betterment. It was very important for me to imbed this knowledge into my images when I was making the project.

D: Did these archival photographs change your own photographic approach to what you were looking for when photographing the coalmine?

DF: They significantly enriched the project. For me, looking at and editing the archive was the most diversified visual journey I have had to date. I work very slowly while photographing — things are carefully considered and arranged — while these archive pictures are more “off-the-hip.”

Also, I did not want to fall into a photojournalistic aesthetic routine that is quite rigid. I believe if you are an image-maker it is extremely important to constantly push the limits of what is visible and thinkable, otherwise everything is going to be homogenous. And if it is, why bother to make images?

D: This picture raises a lot of questions. What’s the story behind it?

DF: This image shows a miners’ changing room. When this particular coalmine was opened in 1964, they invented a very efficient air conditioning system that also was perfect for drying clothes overnight, so miners could wear fresh clothes the next working day.

Each miner has a key to a lock. In the large print of this image, you can see these on the left and right. Each mine has around three thousand similar locks, which would make up around twenty rooms like this one. When the miners finish work they open the lock, bring their clothes and other belongings with them, go for a shower, get changed, hang their fresh clothes, pull them up on the chain and leave it overnight until the following day.

This system has not been changed for nearly fifty years despite the fact that coal companies in the region are extremely wealthy from producing high quality coal for steel production and export worldwide.

D: What is life like for a coalminer in present-day Poland as compared to life before Solidarity?

DF: Quite different, but some aspects have remained unchanged. Of course, labor conditions have improved significantly. Everything is regularly monitored to maintain the very best safety inside the mines.

I learned that the tax rate in the 1960s was 95 percent. This meant that even the smallest rise in food prices profoundly affected most of state’s citizens. Also, if you were a miner you had only one day off per month. The main reason for making Coal Story is the fact that in 1981 prices of basic food products were raised to such a high level that it was unaffordable for the working class; therefore, they went on strike. The core of the communist doctrine had a focus on developing the military potential of the USSR and the coalmines from Silesia were used for their steel production. Mining had become the most important branch of the economy. Having control over coalmines became crucial, and miners who refused to work simply had the power to paralyze the entire economy.

What remains the same today are the miners’ celebrations on the fourth of December.

D: Obviously access played a huge role in both finding the archived images as well as gaining entry to the mine. What would you say was your largest obstacle in the project?

DF: Negotiating the access to such a huge industrial complex proved difficult. I had to wait five months for my proposal to be granted.

When making images inside the mines I always had a supervisor assigned to me. We had quite an interesting relationship. At the very beginning of the project each supervisor felt obliged to tell me which part of the mine would make an interesting story. They were walking me around the mines, pointing things out that should be photographed, which were based on what other photographers had found interesting in the past. I had to maintain a friendly relationship with them and I could not just say I am not interested in being an advocate for their way of seeing. Sometimes, to remain friendly, I was pretending I was making images. When they heard sound of the shutter (with film slides or my camera’s back closed) they were instantly convinced I captured what they wanted. Generally after twenty to thirty minutes they let everything go and I was free to photograph what I wanted.

Also, making images of miners straight after they finished their shift proved quite difficult. Silesian people are generally notorious for their attitude. I waited for some of the opportunities to make portraits for nearly ten months.

---

For more information about Darek and his work, visit: http://www.darekfortas.com