Recent Articles

-

'Photographs Not Taken' Book Signing and Panel Discussion at Photoville

-

The Alphabet of Light, #3, by Kirsten Rian (Dennis Witmer)

-

The Alphabet of Light, #2, by Kirsten Rian

-

Photo Awards Recipient Shane Lavalette's Picturing the South and Kickstarter Campaign

-

Monika Merva discusses her publication, City of Children

Categories

- #SANDY

- 2016

- 27th International Festival of Photojournalism

- Aaron Vincent Ekraim

- Africa

- AIPAD

- Almond Garden

- American Photo

- Anna Beeke

- Aperture

- Art Desks

- Artist Events

- Artist talk

- Award

- Awards

- Barmaid

- Barney Kulok

- Behold

- Best of 2015

- Book Launch

- Book release party

- book signing

- Book signings

- Book-signing

- Bryan Schutmaat

- Call for applicants

- call for entries

- Cara Phillips

- CDS

- Chicago

- ClampArt

- Closing Exhibition

- Competition

- Conservation photography

- Contests

- Cowgirl

- Critical Mass

- Cyril Christo

- Daily Mail

- Daylight

- Daylight Books

- Daylight Digital

- Daylight Digital Feature

- Daylight Photo Awards

- Daylight Project Space

- dj spooky

- Documentary Photo

- DPA

- Dread and Dreams

- E. Brady Robinson

- Eirik Johnson

- Elaine Mayes

- Elinor Carucci

- Events

- Every Breath We Drew

- exhibit

- Exhibition

- Exhibitions

- Fall 2015 Pre-launch

- Festivals

- Film Screening

- Film screenings

- Fine Art

- Flanders Gallery

- Fotobook Festival Kassel

- Françoise Callier

- From Darkroom to Daylight

- Frontline Club

- Gabriela Maj

- Gays in the Military

- george lawson gallery

- GuatePhoto

- Guatephoto Festival

- Hariban Award

- Harvey Wang

- hochbaum

- Home Sweet Home

- Huffington Post

- Hurricane Sandy

- Interview

- J.T. Leonard

- J.W. Fisher

- Janet Mason

- Jess Dugan

- Jesse Burke

- John Arsenault

- Jon Cohen

- Jon Feinstein

- Katrin Koenning

- Kuala Lumpur Photo Awards

- Kwerfeldein

- L'Oeil de la Photographie

- LA

- Landmark

- Leica Gallery

- Lenscratch

- LensCulture

- Library Journal

- Lili Holzer-Glier

- Lori Vrba

- Lucas Blalock

- Malcolm Linton

- Marie Wilkinson

- Mariette Pathy Allen

- Michael Itkoff

- Month of Photography Los Angeles

- Mother

- Multimedia

- Nancy Davidson

- New York

- New York City

- News

- NYC

- ONWARD

- Opening

- Opportunities

- Ornithological Photographs

- Out

- Party

- Philadelphia

- Photo Book

- Photo Booth

- photo-book publishing

- PhotoAlliance

- Photobooks

- Photography

- Photography Festival

- photolucida

- Poland

- portal

- Pre-Launch

- Press

- Prize

- PSPF

- Public Program

- Raleigh

- Rayko Photo Center

- Recently

- Rencontres De Bamako

- Reviews

- Robert Shults

- Rockabye

- Rubi Lebovitch

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Seeing Things Apart

- SF Cameraworks

- silver screen

- Slate

- slideluck

- Sociological Record

- Soho House

- spring 15

- Spring 2016

- Stephen Daiter Gallery

- Sylvania

- Talk

- Tama Hochbaum

- The Guardian

- The Moth Wing Diaries

- The New Yorker

- The Photo Review

- The Solas Prize

- The Superlative Light

- The Telegraph

- TIME

- Timothy Briner

- Todd Forsgren

- Tomorrow Is A Long Time

- TransCuba

- Upcoming events

- USA Today

- VICE

- Vincent Cianni

- Visa Pour L'Image

- Vogue

- We Were Here

- Wild & Precious

- Wired

- Workshop

- Zalmai

- Zofia Rydet

News

'Photographs Not Taken' Book Signing and Panel Discussion at Photoville

Posted by Daylight Books on

Come out to Photoville NY for a panel discussion and book signing of 'Photographs Not Taken'. A photographic book, edited by Will Steacy, that shows no photographs but presents engaging and enveloping words that describe photographs.

This event is on Friday June 29th from 6:30-7:30PM, featuring Will Steacy, Elinor Carucci and Ed Kashi.

Information:

The Alphabet of Light, #3, by Kirsten Rian (Dennis Witmer)

Posted by Daylight Books on

Photograph by Dennis Witmer Wildflowers in clear-cut, Evans, Washington, June 11, 2012

Intention

“I know so little about photography, but when I was teaching first graders, I had them make a camera with two hands coming together in a frame - then the snapshot poem that came from it. It was so much fun to see all these little bodies running all over the lawn stopping, holding up their hands to capture what no one else was seeing,” poet and essayist, Melissa Madenski, tells me the other day.

This got me thinking. The same words, the same sky, all of us walking the same soil, and by and large maneuvering the same dog-eared page turns of life, death, and love. Yet none of us see exactly what the person next to us is seeing. Not a single one of us. Perhaps the fundamental core content is the same, but there’s so much more to contextualizing imagery--individual histories and memories spilling into every moment, color, and line the eyes intake. And from this perspective, everything held within every street corner, out any window, looking up from any pasture edge or out across any bluff, is infinite. Even when it’s quiet. Daily. Seemingly ordinary.

Kids get this. And the elation of running around with a finger frame held to their eyes is a vector of discovery, the kind of awake-ness that often gradually slumps as the architecture of daily grown-up life builds itself around us from year to lumbering year. How to visualize, accurately, the now of experience, is a feat I’ve yet to nail down, whether it be via camera, paintbrush, or pen.

Add interpretation to the mix and that’s another set of slippery syllables all together. It occurs to me that, as with the way a photographer looks and the decisions driving the fingerpress of the shutter, interpretation is an act of intention. An effective image inextricably links hands with a viewer and in that second, leaves the photographer. We take a picture, give it away, take, give, and this call and response cycles through every one of our pieces, like memory, like morning.

Recently, the inimitable photographer Dennis Witmer wrote to me: “More and more, I think of photography like poetry--a poet doesn't invent words, they just use the same words as everybody else, but they use them with a different intensity--they create patterns of words that are meant to be repeated and to carry meaning. Everybody writes, but very few people are poets. It seems to me that the meaning of photographs comes from exactly the same place as the meaning in poems--from the intentions of the artist...Learning to make photographs that say exactly what one intends to say takes just as long as learning to write poetry--I want to make pictures that are worth looking at again and again, that carry beauty and meaning.”

Dennis takes big photos of big land. And I don’t mean scale, not the trendy mural-size deals, I mean his images are rich. Vast. He looks out across the Alaskan Brooks Range and recognizes wholeness in the emptiness, found in the forgetting. He looks out and lets himself see. And happens to include his camera in this process.

In a recent collaborative book, Robert Adams said, “When I study Witmer’s pictures I think of pictures from the Hubble telescope. They document the same cold—nature’s apparent indifference—but also the same deep mystery, an unknown so impenetrable that only a fool would claim to know enough to write off hope, even hope for a caring and forgiving God.”

Measurement by sightline. Trust by peddling containment within a square. Reconciliation of truth caught in a moment before it changes and becomes someone else’s moment. Maybe we shoot to qualify the tone of voice in our head saying, here, look here, see what is here.

Some of Witmer’s images are at: http://denniswitmer.wordpress.com/

The Alphabet of Light, #2, by Kirsten Rian

Posted by Daylight Books on

Photograph by David Maisel

The Alphabet of Light

Conscientious, a response

I played in a band for 15 years with a brilliant guitarist nobody’s probably ever heard of. He used to say the best songs and best songwriters will never be heard. The world’s best guitarists are noodling around in their basements with some Fender amp tweaked up, bending notes through hot-wired distortion and wah pedals that would defy Hendrix.

I believed him then, and I believe him now. And I think this idea transcends mediums and extends to any and all creative fields, including photography. And while to some extent I don’t like this idea that the most singular and elevated translations of thoughts and interior space are most likely not gracing the eyes and ears of all the rest of us, I essentially choose to remain motivated and inspired by knowing at least they’re out there somewhere. The fully-realized, originally-conceived and soulfully executed photo projects exist whether or not I see them. The issue to me is one of trust.

And the thing is, maybe my life is just particularly graced by a lot of compelling artists, but I also actually see incredibly mindful work that keeps me believing in this medium. Photography is not in a crisis, for heaven's sake. There's no stasis any different than the kind of stasis in 1974, in 1988, in 1996, in 2012, or any other random year...every single creative medium is perpetually in a state of quasi-stasis--it is plum difficult finding creative thinkers capable of producing original songs, paintings, poems, essays, and certainly photography. It has been this way since the beginning of time. But original artists and lingering images do come along. And they resonate. This very ‘history’ that is criticized is in itself a tool of reference: has there ever been, say a decade period of time in the past 200 years, with an utter absence, a void, a complete mssing in action of growth in vision, without a handful of stand out photographers who’ve stretched the definition of photography and done so using whatever tools at hand at the time? The tool of the medium can’t be blamed, the digital realm and all the gadgets that come along with it. It's the brain behind the tool that's composing, reflexively selecting the moment to hit the shutter, and frankly those brains are hard to find. Thus, it feels stagnant sometimes. But we all must believe in something, intangible or otherwise, about this dang field otherwise we wouldn't keep producing images and writing about them.

Yes, this is an art conversation, not exclusive to photography. No period of time and no artistic medium is all at once static or all at once an eruption of brilliance. It’s both all the time. And that’s why we make art and that’s why we keep opening the books of the artists we appreciate and that’s why we value risk and expansiveness, because we realize how rare it is. But rarity is not the same as absence.

“...how can we turn around, to look at and move into the future?” was recently asked by the ever-thoughtful Jörg Colberg. By referencing history to trust that it’s there. Substantive. Present. Ready. At times even more complex and layered than it was 50 years ago. Better? In parts, and not in others. Will we still be needing to slough through images reflecting latest media trends and mfa regurgitations and forgive me, but please shoot me now if one more earnest photographer plops down their portfolio and tells me they’re exploring how the interior and exterior spaces interact? Yes. We will still be plowing through all that. But as always, the great work, the masterfully rendered photograph spilling story and multiplicity of thought and emotion will be there, too. It’s up to us to believe it’s there, to try to find it, or hell, make it, using whichever tools we choose to augment the box and glass and light contraption we call a camera.

Compelled and curious by this query at hand, I asked a few of my friends whose image-making I respect to respond to my question: What state do you feel photography is in right now? The responses I received were beautiful, at times riveting, heartened. Stay tuned, more artist responses and conversation around this subject to follow next week, but here are a few.

By Kirsten Rian, with the following byline, also a response to Colberg’s piece: painter; writer; photography curator who doesn’t often get paid for her work but who does it anyway; editor and sequencer because God bless ‘em but sometimes photographers are freaking hopeless at editing their work; and gulp, working jazz musician (and if you want to talk about conservatism try being on a three hour gig with non-improvising, music-reading-tethered people calling themselves jazz musicians. It’s so far past painful I have to stop here or this will turn into a rant of vast proportions).

“Last week I read "Black Box," a powerful, and haunting new story by Jennifer Egan published in The New Yorker . Since I am apparently somewhat of a luddite, and I relish the feeling of paper in my hands, I subscribe to the magazine in paper form, rather than reading it on a laptop or a sleek iPad. Later, I learned that Egan had written the 8500-word story to be released on Twitter, and it was indeed released one tweet at a time, with the 140-word limit imposed by this form. The story was brilliant not because of this limitation, and not in spite of it. It was integral to it, yet the story also stood alone, as a potent work of fiction.

When the typewriter or, decades later, the word processor was invented, did it negatively impact the work of essayists, fiction writers, playwrights? I doubt it. The constraints and possibilities placed on a medium contribute to what artists can do in a positive way.

In the past century, as film and lenses got faster and cameras got smaller, street photography and photojournalism were impacted and enabled. Likewise, perhaps the f64 group that preceded would not have existed had it not been for the limitations (or, simply, innate characteristics) of slower films and larger cameras.

The limits of photography have always existed in a changing, fluid dynamic form. Cameras, lenses, papers, films, and, yes, digital technologies come and go. They are the current on which photography rides, but not the substance of what makes a photograph a worthy work of art.”

--David Maisel

“I'm the wrong person to ask - I would much rather get out my Sudek or Strand or Renger-Patzsch books for the thousandth time, while grumpily yelling at modern/post-modern art and photography to get off my lawn...”

--Bruce Haley

(and here is a link to the Colberg posting I reference: http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2012/06/photography_after_photography_a_provocation/)

Photo Awards Recipient Shane Lavalette's Picturing the South and Kickstarter Campaign

Posted by Daylight Books on

Photo Awards Juror's Pick Shane Lavalette is just days away from the conclusion of his Kickstarter campaign for the publication of his body of work on the American South. This project grew out of a commission from the High Museum of Art in Atlanta as part of their Picturing the South series, which has included past artists, such as Sally Mann, Emmet Gowin, Richard Misrach, Dawoud Bey, Alex Webb and Alec Soth. This month, Lavalette exhibits new work along side Martin Parr and Kael Alford as part of the MoMA/High Museum partnership.

Kate Levy interviewed Lavalette about the recent work.

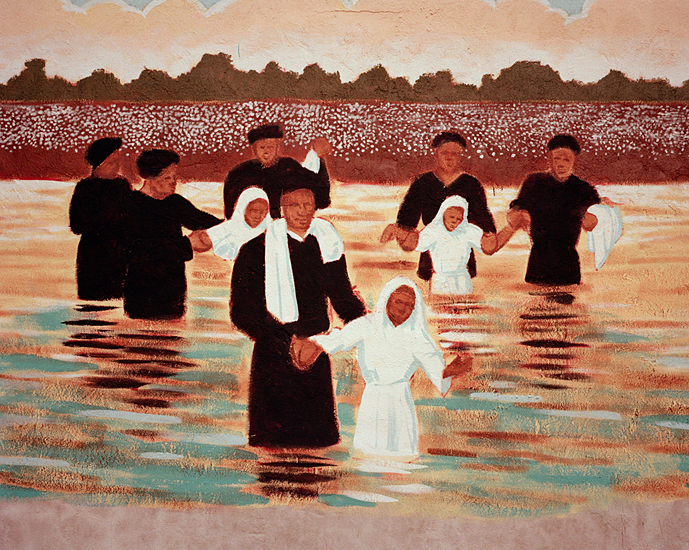

Kate Levy: In his essay, Tongue After Tongue, Tim Davis discusses your point of entry into the South as the vernacular music of the region. Your work employs a rhythm which seems informed by the rich history of oral tradition and musicality. What specifically have you been listening to, and what about this music calls out to you to transcribe it visually?

SL: Exactly. I've always had an interest but in recent years was really taken with blues, old time and gospel music - each of these genres have their particular style and lineage, but they all tend to touch on similar stories and themes about daily life, struggle, love, death, nature, religion, etc. I've been listening to the likes of Doc Watson, Roscoe Holcomb, Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, Leadbelly, Elizabeth Cotton, among others. When I began my project, which was a commission for the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (where the work is now on view), I set out not to create any documentary about Southern Music but something more distinctly lyrical, inspired by the music. In particular, I'm interested in how the music is shaped by the landscape of the region as well as how our understanding of the landscape is shaped by the music.

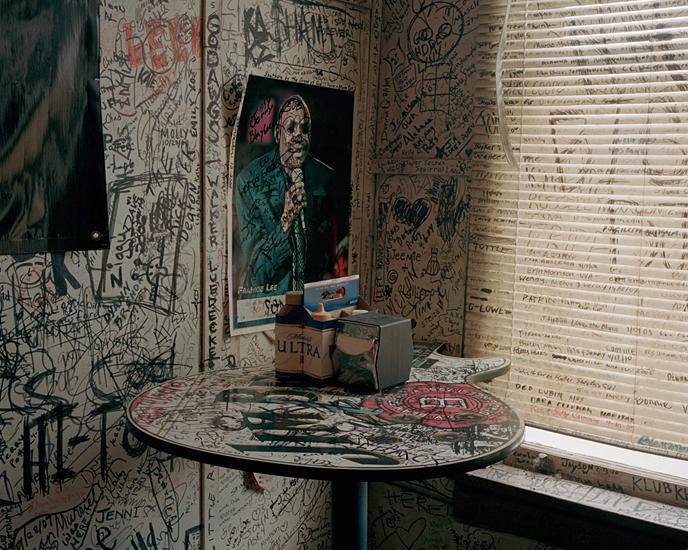

Copyright Shane Lavalette

Copyright Shane Lavalette

KL: You seem to adapt tactics gracefully employed by the likes of Peter Sekaer and Walker Evans in that much of your documentation is centered around sineage, markings and visual articulations, sometimes weathered by years. What specifically do you hope to translate about Southern history and livelihood by depicting these aged cultural signifiers?

SL: In the same way that some parts of the musical histories I am interested are slowly fading and changing, so too is the cultural landscape. It's weathered by the years. Some things are forgotten, others are cherished and carry on. Some of my photographs are in color, others are in black and white. I was interested in the idea of using (and mixing) both to talk about this aspect of time and in some instances timelessness.

Copyright Shane Lavalette

KL: What particular regions were you drawn to, and how did the course of your travels bring you to these places? How long were you traveling in the South?

SL: I was primarily drawn to the 'Deep South' and spent most of my time in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. Though I also spent time in Tennessee, Florida, the Carolinas, etc. I spent the whole of the Summer of 2010 living out my car, camping and staying with kind folks, much of the Summer of 2011, and then various shorter trips to specific places in between.

KL: You're from Vermont. Were there times you felt like a fish out of water? What were your most difficult points of entry?

SL: Certainly. In a sense, I am. Though, at this point it's something I've become accustomed to, having photographed in Ireland, India, and other distant places. I really fell in love with the South, so it wasn't hard for me to aclimate but there are always times where you're reminded you're just not a Southerner. The hardest points of entry tended to be into the personal lives of people. Fortunately I met a lot of kind strangers that became friends, welcomed me into their homes and shared their stories, recommendations, couches, etc. The way I travel is usually dictated by the people I meet and where or who they refer me to. These relationships are important to me personally but also to the pictures.

When I was in Natchez, Mississippi I met a man named Alvin who played organ and sang in his local church choir. Not only did he welcome me into his home, but he actually opened up and sang for me. The result is my first video piece I've ever shown, which is simply Alvin singing silhouetted against the window in the living room. This was a very memorable, and completely moving moment for me.

Copyright Shane Lavalette

Copyright Shane Lavalette

KL: What are you working on now?

SL: The project has always been moving towards a book, so I'm in the process of editing, designing and producing my first monograph which will have images from the exhibition at the High but also a number of others. The book form lends itself nicely to the musical nature of the work, so I'm thrilled to be making this happen. The project is currently being crowd-funded on Kickstarter until this Friday, June 22nd if any readers are interested in pre-ordering a copy or making a pledge to support the project in general.

To see more of Lavalette's work, visit www.shanelavalette.com

Monika Merva discusses her publication, City of Children

Posted by Daylight Books on

Kate Levy and Monika Merva met to discuss Merva's Publication, City of Children.

Kate Levy: Can you tell me more about your specific experience in this one institution where the photographs take place? How did you get the opportunity to take photographs there?

Monika Merva: It was kind of wonderful. I had always done black and white street photography. But while I was living in Hungary [Merva's Hungarian], I wanted to work with a community of people, and photograph something I could come back to over the years. I was talking with one of my cousins. She told me about this place called the City of Children, that I might love it. But then she told me I’d never get in there, and to scratch the idea.

KL: That’s a great way to motivate you.

MM: I took that in stride. A few days later, I had to deliver a package for this elderly woman who had a friend living in the States. She was the director of the Agricultural museum in Budapest. She said, “I hear you are a photographer, what do you want to do?” I told her that I really want to go to this place, the City of Children, but I hear I’m not going to get access. She told me she’s very good friends with the director and she’ll put a good word in for me, but that it would take time.

KL: No way...

MM: So a year later, I get a call. This was 2001, back in New York, July.

KL: Had you persisted?

MM: No, I just let it go. I sent one letter with an image and told her I was looking forward to hearing from her. So when they said I could come, I was getting ready to go to Sturgis, South Dakota, to photograph the motorcycle rally. So I asked if I could come the next May. She said yes, but that I could only come for a day to see how the kids responded to my photographing. When I finally arrived, I was assigned to one girl to follow around. I speak Hungarian, but I have an accent, so I sound a little funny. I was grateful about that. There was something about being awkward that made me more approachable. I had my camera with me. I use a medium format, no flash, no tripod. I tried to be unassuming as possible. At the end of lunch on my first day there, the director told me that I was more than welcome to stay and photograph. I was assigned to one group, because they are set up like houses. The adult guardians in that house are still some of my dear friends.

KL: How often did you go?

MM: I went every year, in May, for a week. A total of eight years. In the end I only spent 58 days with them.

KL: Was it hard to get back in?

MM: It was immediate. Every year I’d go back I’d bring 11”x14” prints. I made sure all the kids got a print. I gave them to administration received for their archives, as well.

KL: Did the administration or the youth have any opinions about the pictures?

MM: Yeah, the kids had ideas about what they wanted to do. They’d often goof off for the camera. But we collaborated also. We’d sit around and talk and make pictures.

KL: Did they ever approach you with their own ideas?

MM: I would go along with it, but I rarely used them, because it was so different from what I was trying to do.

KL: Are there any that you used?

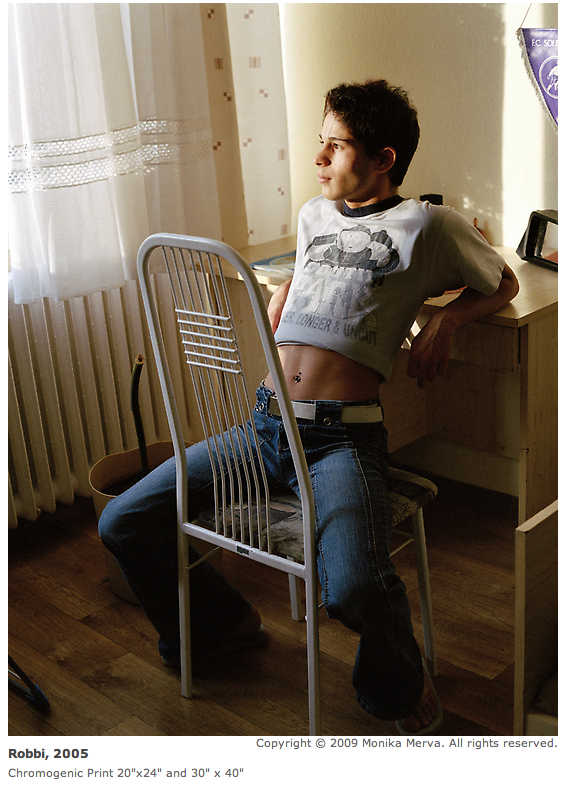

MM: The one of Robbi. He would always tell me these stories about his girlfriends. I would think to myself that these stories were just not true; he’s gay and not saying anything about it. That year, he finally came out and asked me to take a new portrait. So I said, let's go in your room and sit, and see what happens. This is what came out.

KL: There are several photographs where the kids clothing conveys a sort of semiotics, eluding to certain ideas, but ultimately nonsensical as childhood itself.

MM: None of the kids know what South Park is.

KL: How are their lives after they leave the home?

MM: They don’t have mentorship afterwards. I tried to explain it to some of the staff and the director, but they didn’t understand how a stranger would come in and take someone under their wing. So the kids go out into the “real world.” They either enroll in school, or they end up back on the streets. A lot of them start families with each other, or with those from outside of the home. They start their own families at 19 year old and move in with the other person’s extended family. One of the girls all ready has two children and lives with her husband’s mom.

KL: It seems like they have a pretty free reign.

MM: It’s very free. Of course they have a curfew and have to be on the grounds at specific times for meals.

KL: But is it regimented by laws? When I worked in a youth home, we were required to check on the kids while they were sleeping with a flashlight every fifteen minutes.

MM: No, its very loose. They have two adult guardians during the day, and in the evening, a different person would do the night shift. It wasn’t strict because they wanted the kids to self-regulate and maintain their daily schedules. They would basically just hang out. I just chalked it up to them not having enough people to keep a very close eye on them. They really spent a lot of time waiting for the next thing to happen.

KL: It seems like there is a lot of importance placed on them when they are children, but when they are adults, they are out the door.

MM: The country and the home don’t have enough resources. In the eight years I went there, they only had two men working there the entire time. The rest were retired school teachers.

KL: Can you go into a little bit more detail about the political climate in Hungary? What’s happened since communism, theres been a restructuring, right? How that’s effected the institutions set up for social welfare?

MM: When I started this project, I didn’t really pursue any contextualizing political issues, the fall of communism and the aftermath. I didn’t want them to feel I was coming in there and passing judgement on how the government was treating the children. I didn’t want to get into it in a political realm. Slowly I learned things on my own by hearing what people were discussing. This home started in the 1950s. Children were everything; they were held in such high regard. You do everything for the child. Even now that holds true. This place is government funded for them to live there. They really try and work with the kids with the limited resources they have. There’s definitely places like this that are closing down. There were 50-60 throughout Hungary, and they are closing one by one, relocating those children to homes that are still open.

KL: They are breaking up a lot of close bonds between kids.

MM: And between the kids and staff : A woman named Vera, an adult guardian, she was in her forties or fifties when I met her. She has a daughter herself. She grew up in the City of Children because her mom put her there. When she was 18, Vera left, trying to get her place in life situated. She says she felt terrible when she left, and she just wanted to go back. So she came back, and now she is there as an adult guardian.

KL: Did you photograph her at all?

MM: I did make a few portraits of her, but I chose not to include them, because I wanted to elaborate on how I felt there, the overwhelming feeling of being surrounded by kids. The adults are in the background.

KL: I think I get why you are thinking less about the social phenomenons surrounding institutions, the politics of it. This work is so much more about the strangeness that is childhood, the disorientation.

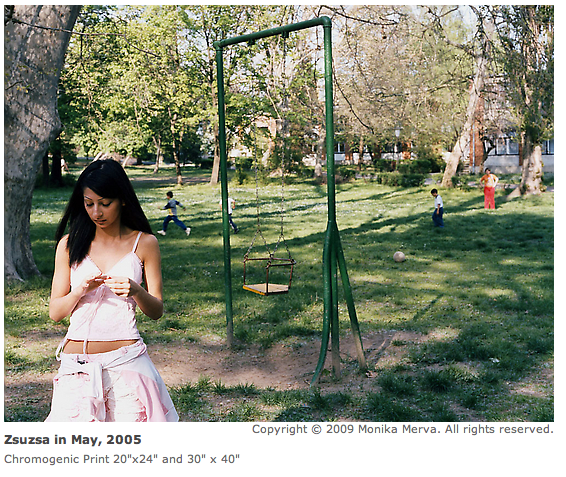

MM: I went in with no idea of what I was doing. I was very curious about this place. I’d never heard of anything like this in the US, and the home is located in a beautiful countryside. Every year that I went back I started to realize what I was photographing. The awkwardness of being a child, of being a teenager. I was photographing that waiting for something to happen, waiting to be an adult, yet on the flipside, the children have all ready been exposed to some major, adult issues. They’ve experienced so much, but they have no idea. The universality of being a child, it doesn’t matter what you have, where you are, who you have, whatever percent you are in. We are all humans, and we all experience this lonelineness of life, waiting for something to happen. We long, we love; everyone can understand that. I am very interested in trying to show the soul of a person, in finding something that will resonate with the viewer. I want to see what is not visible. I am looking for the pride and strength in anyone.

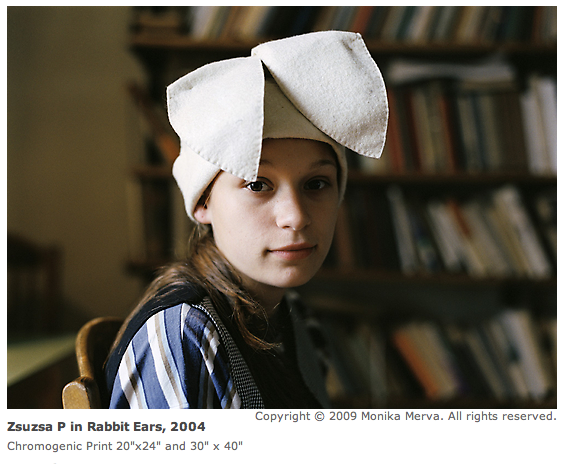

KL: Maybe that explains your interesting choice of the cover.

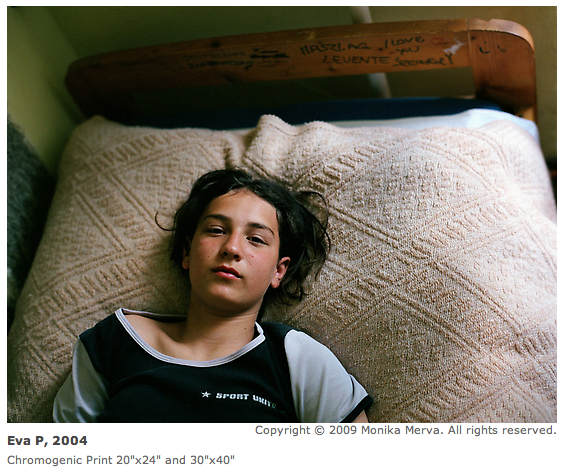

MM: We went through several options for the cover. Originally the cover photograph was going to be Eva, the androgynous looking girl lying on the bed. Its an engaging image, it gets picked for a lot of shows. But that image I would think would be deceiving for this body of work. I love the photograph we chose it because her eyes follow you. When its in the bookshop she’s looking at you all the time.

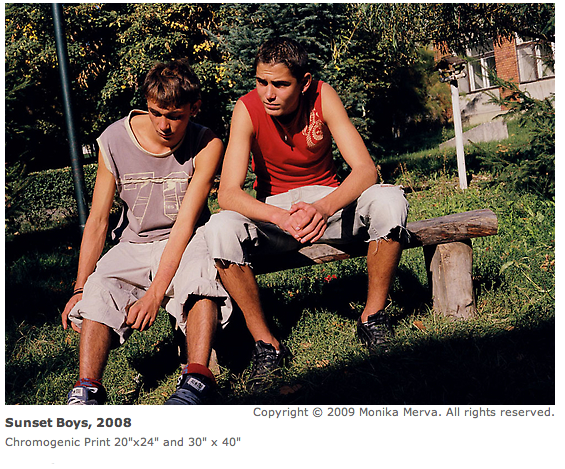

KL: I thought it was a strange choice at first. At first I was trying to find the political element in the photographs you made. The photograph of Zsuzsa P in Rabbit Ears doesn’t seem very specific--it could be anywhere. But then I look at it again, and she is there. Also, it makes sense that some of the more environmental images that you make that are so compelling wouldn’t make a good cover shot because there is no contact between the viewer and the subject. I think that photographers can easily write off this motive of looking for the soul while taking a photograph. With the evolution of the medium, and its interactions with other mediums, photography is not just about the essence of a subject. To state that as a goal, to want to do that, is now unexpected. It’s human, and gets at what you were saying about having a common denominator for the viewer to relate to. Perhaps helpful or therapeutic for the child to engage them in this type of looking as well.

MM: There are trends, I feel like many photographers are sort of mocking of everything right now. It just makes me sad. Is that work really healthy? Is that really a good thing to do?

KL: I think what is really great about your work is that you are not trying to make universal commentary about human beings, despite being universally relatable. A friend once said of my own work, "you really don't have a very positive projection for the fate of humanity, do you?" You are trying to tap into a place where we feel, by looking at and talking about a group of people. And I think the more photographers who do that, the more effective photography is as a social mechanism. There’s poignancy to different artists looking at similar phenomenons in different areas. This is not to say that there aren’t really some compelling things besides the gaze of your subjects. The objects you include in the frames are definitely along the lines of what we were talking about a bit earlier--this idea that the youth have seen so much. I think maybe many people experience childhood as incredibly violent, sensual, wanting, waiting, yearning, frustrating and then on the other hand, so utterly dopey, this state of...”whatever!” I was really struck by so much of the sensuality in the pictures, especially the photograph of Robbi. It wasn’t overt sexualization, but they aren’t the most socially harnessed photographs of children either. I was really struck by the primal energy in them.

MM: But it happened naturally.

KL: I think this is where you are scratching below the surface. I was talking about this last night with some friends-- ghost stories, horror stories are so important for children.

MM: The kids and I talked a lot about vampires

KL: The psychology of the child, he or she needs an outlet for morbidity.

MM: Fear is exciting. I think it’s groundwork for them. This morbidity is and exercise for later times, and for bigger issues.

KL: It’s ironic because at the same time the kids have all ready seen so much. I think its really think its important to continue to make work like that, to explore what it means to be a child and sensual, natural, alive, confounding the boundaries between everything adults have ordered into different places, because that helps us decompartmentalize our own worlds.

MM: Do you remember when Sally’s Mann’s Immediate Family came out. Virginia wrote that letter to the New York Times Magazine. “Why is this picture of me so bad? Why did they have to block my eyes out?”

KL: That’s even more violent. Yeah, now lets just show her body!

MM: And now she can’t even see you looking at her.

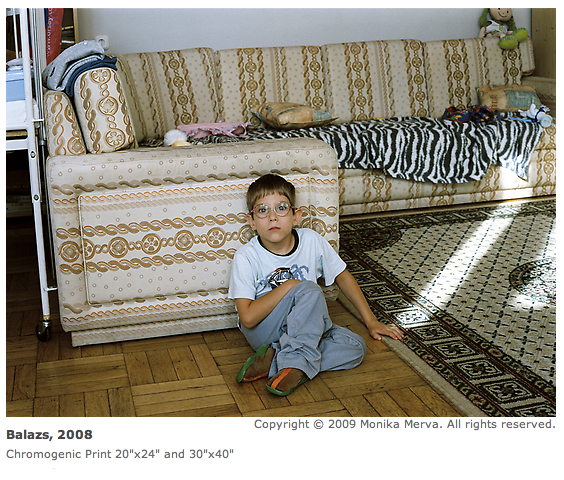

MM: This one, this boy cant walk, so he uses his arms to drag his body behind him.

He is so bright.

KL: I respect the choice to make the photograph of his eyes so prominent, then. What could have been a formal photograph of his motion, you chose to focus on his eyes.

MM: It’s who he is.

KL: Have these kids been photographed much before this, was it socialized to smile for the camera?

MM: A lot of times wed be hanging out, they’d forget the camera. Sometimes they’d, as I said, asked me to take their picture. After years of coming back, they’d understand how I make pictures.

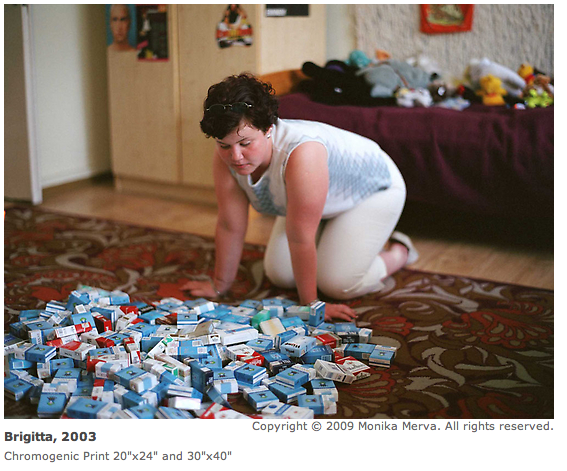

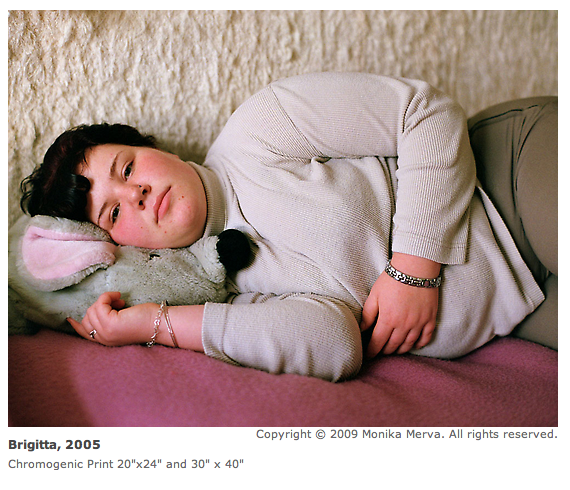

KL: Brigitta--I keep looking at this one. I can’t imagine what kind of person she must be.

MM: The first time I saw Brigitta she was counting her collected boxes of cigarettes. It’s very much an Eastern European thing to collect cigarette boxes and beer bottles. She was allowed to keep that collection. I think anyone from E. Europe knows that. After I met her, I went into the kitchen and talked with the adults, and I asked, “who is that new girl?” They’re like, “Ohhhh Brigita.” So, Brigita and I started hanging out. She wouldn’t go to school; she would sleep in late. I asked her why. She thought everything was so boring. She didn’t know what she wanted to do. She didn’t have any dreams. She said no to everything. The next year I came back, I asked if she had thought about her life. She said she was working in a pastry shop and really loved it. She was always such a hard nut, swearing, smoking her cigarettes, wearing tight clothes. She didn’t care and I loved her for everything. When she was 18, I met her boyfriend; he was 35 at the time. They are still together. She moved in with him. The following year, I came back, she had graduated and invited me to her house. She baked me cookies! That photograph of the kitten’s claws, those are her hands feeding the kitten. She had found it on the street.

KL: The hardest rocks have the softest centers and vice versa.

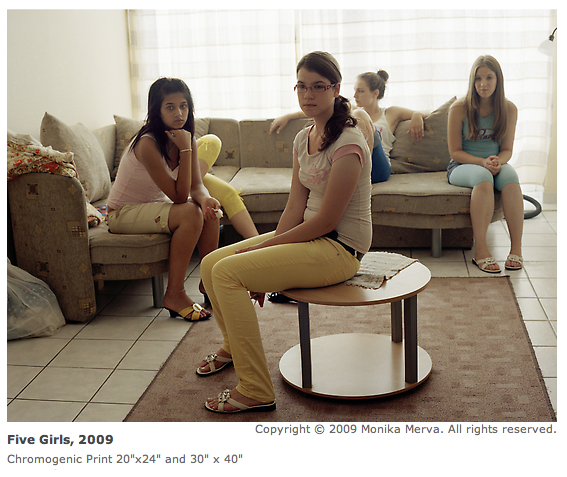

Did you ever have any altercations with the kids?

MM: Well, my last year, 2008, I knew it was going to be my last year. I knew I had to finish this book. I was going to say goodbye, and maybe get a few pictures. I walked in, and they were just like this, sitting. Eva was in the middle, with these two girls who are twins. This girl that you can’t see had always wanted me to photograph her, but I could never get a good picture of her, so its fitting that you don’t see her. So, I walked in, and I took this picture immediately before I said anything. I came in closer, put the camera down, I told them I was looking for all of them. I said, “Lets get some pictures for the last time.” And Eva says no. She said she didn’t have makeup on, didn’t like her outfit, had to do her hair. But she was always down for it.

KL: And they know how you photograph, so...

MM: Exactly. My eyes started welling up with tears because they were saying no. And the idea that this is the last time. I tried to sit and talk with them, but I was sobbing on the inside. So I left. Ava came after me, and said, “I’m sorry we didn’t let you take our picture, we just weren’t feeling it.” I told her I totally respected that, but that what made me sad, was her saying no has allowed me to really let it end. That it was a confirmation. No one had ever said no. But they are all on Facebook, so I look at their pages, and I can see how they are.

KL: I love that that is the first picture of the book. Also, your formal spatial shots are quite different.

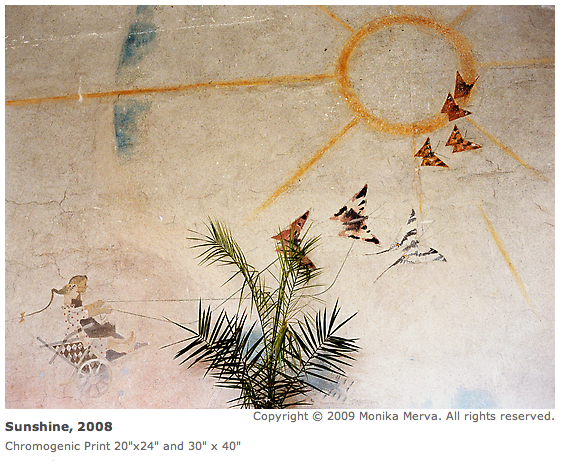

MM: While I was showing the book to people in its mid-stages, a couple of people told me that I had all the characters but I hadn’t set the stage yet. It is totally horrifying for me to take a picture without a person in it. Stilllife work scares me. When I went there I was really pushing myself to find a life behind inanimate objects. Get a soul or a presence. I wanted the objects to breathe.

KL: That makes a lot of sense given your technique in photographing people. You are successful in seeing a soul, but I’m not sure it describes anything about the space logistically. These seem to do something energetically similar to the way you make portraits of the children. There are no establishing shots.

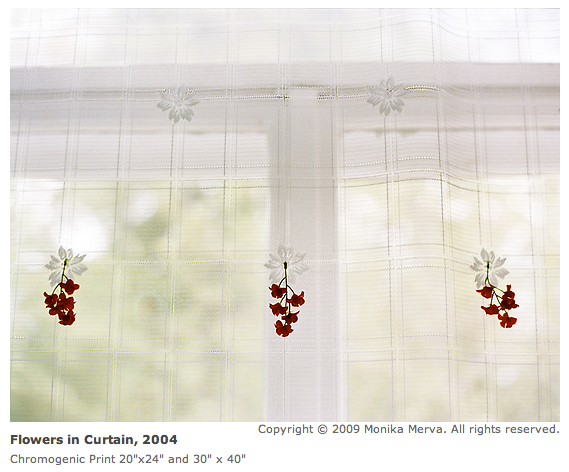

MM: For me, the buildings were irrelevant and nondescript. They decorate their curtains with plastic flowers. I had taken pictures of the building but it didn’t do anything. It didn’t explain anything.

KL: Why did you put this photograph first in the main sequence?

MM: Its the window leading you in.

KL: It also seems like you are unveiling something secret, veiled, confounding and, as you elluded, timeless. I really appreciate you withholding of a lot of circumstances, there is no editorial time lapse, no “this is the birthday party,” “this is them sleeping.” No “day in the life.” It’s day to day, but you don’t get the stigmatization that comes along with, the “look, they do all the things we do” or trying to show every part. It’s very much about the energy of endless kids everywhere, and the endlessness of childhood.

MM: It was important not to exploit their private lives. This is intimate information. It’s not going to help for my intentions with this work, using the information in an explicit way. It was about my experience there.

KL: I love that you are able to make very strong pictures and be as ethical as you want to be about it. It’s a very difficult thing to make people feel comfortable and make interesting pictures. Its inherently violent to flatten people, to use objects to describe situations. Because objects and people aren’t the same. I think that goes back to the cover, the gaze still penetrates.

MM: I’m also very aware of, when I’m composing, what’s around the photograph, controlling what there is in the frame. I don’t want anything in the picture to be misleading.

KL: It’s funny, because sometimes it takes a little more arranging to present the most accessible truths to the viewer.

MM: Where I put myself, or what couple of things I take out makes worlds of difference.

KL: Nayland Blake talks about leaving things in, not omitting things because you think that they don’t fit into a certain realm you are trying to talk about. Let the idiosyncratic mishaps happen. I appreciate that you are coming from the opposite place, because I think what you are saying is that something in a photograph can be really misleading that is, in reality, part of something. You framing it is going to take on different meaning so you do have to omit things for the sake of the subject. I think that is one of my favorite fallacies of photography, that making unaltered pictures is the best way not to mislead.

MM: You have to be conscious of your environment, not only when you are with the camera.

KL: It teaches you about how you judge people based on other things. it teaches you to take things with a grain of salt and take them seriously all at the same time.

To see more of Merva's work, visit www.monikamerva.com