Kate Levy and Monika Merva met to discuss Merva's Publication, City of Children.

Kate Levy: Can you tell me more about your specific experience in this one institution where the photographs take place? How did you get the opportunity to take photographs there?

Monika Merva: It was kind of wonderful. I had always done black and white street photography. But while I was living in Hungary [Merva's Hungarian], I wanted to work with a community of people, and photograph something I could come back to over the years. I was talking with one of my cousins. She told me about this place called the City of Children, that I might love it. But then she told me I’d never get in there, and to scratch the idea.

KL: That’s a great way to motivate you.

MM: I took that in stride. A few days later, I had to deliver a package for this elderly woman who had a friend living in the States. She was the director of the Agricultural museum in Budapest. She said, “I hear you are a photographer, what do you want to do?” I told her that I really want to go to this place, the City of Children, but I hear I’m not going to get access. She told me she’s very good friends with the director and she’ll put a good word in for me, but that it would take time.

KL: No way...

MM: So a year later, I get a call. This was 2001, back in New York, July.

KL: Had you persisted?

MM: No, I just let it go. I sent one letter with an image and told her I was looking forward to hearing from her. So when they said I could come, I was getting ready to go to Sturgis, South Dakota, to photograph the motorcycle rally. So I asked if I could come the next May. She said yes, but that I could only come for a day to see how the kids responded to my photographing. When I finally arrived, I was assigned to one girl to follow around. I speak Hungarian, but I have an accent, so I sound a little funny. I was grateful about that. There was something about being awkward that made me more approachable. I had my camera with me. I use a medium format, no flash, no tripod. I tried to be unassuming as possible. At the end of lunch on my first day there, the director told me that I was more than welcome to stay and photograph. I was assigned to one group, because they are set up like houses. The adult guardians in that house are still some of my dear friends.

KL: How often did you go?

MM: I went every year, in May, for a week. A total of eight years. In the end I only spent 58 days with them.

KL: Was it hard to get back in?

MM: It was immediate. Every year I’d go back I’d bring 11”x14” prints. I made sure all the kids got a print. I gave them to administration received for their archives, as well.

KL: Did the administration or the youth have any opinions about the pictures?

MM: Yeah, the kids had ideas about what they wanted to do. They’d often goof off for the camera. But we collaborated also. We’d sit around and talk and make pictures.

KL: Did they ever approach you with their own ideas?

MM: I would go along with it, but I rarely used them, because it was so different from what I was trying to do.

KL: Are there any that you used?

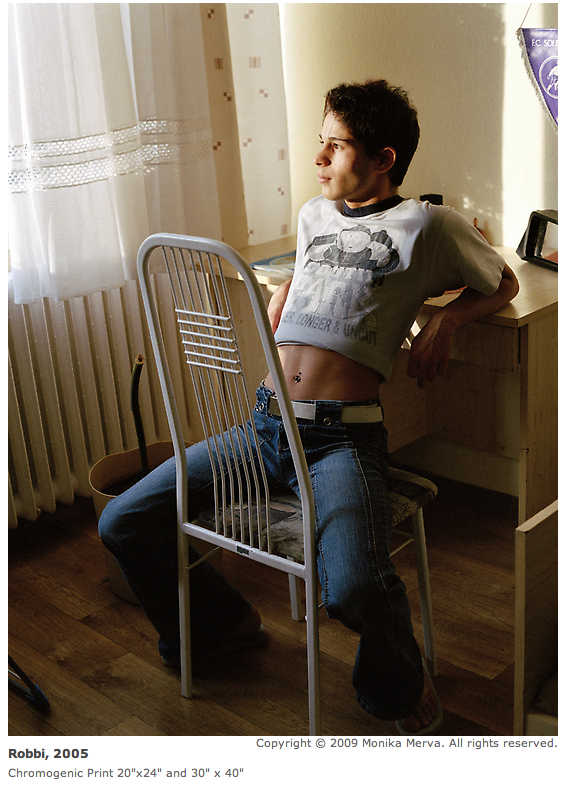

MM: The one of Robbi. He would always tell me these stories about his girlfriends. I would think to myself that these stories were just not true; he’s gay and not saying anything about it. That year, he finally came out and asked me to take a new portrait. So I said, let's go in your room and sit, and see what happens. This is what came out.

KL: There are several photographs where the kids clothing conveys a sort of semiotics, eluding to certain ideas, but ultimately nonsensical as childhood itself.

MM: None of the kids know what South Park is.

KL: How are their lives after they leave the home?

MM: They don’t have mentorship afterwards. I tried to explain it to some of the staff and the director, but they didn’t understand how a stranger would come in and take someone under their wing. So the kids go out into the “real world.” They either enroll in school, or they end up back on the streets. A lot of them start families with each other, or with those from outside of the home. They start their own families at 19 year old and move in with the other person’s extended family. One of the girls all ready has two children and lives with her husband’s mom.

KL: It seems like they have a pretty free reign.

MM: It’s very free. Of course they have a curfew and have to be on the grounds at specific times for meals.

KL: But is it regimented by laws? When I worked in a youth home, we were required to check on the kids while they were sleeping with a flashlight every fifteen minutes.

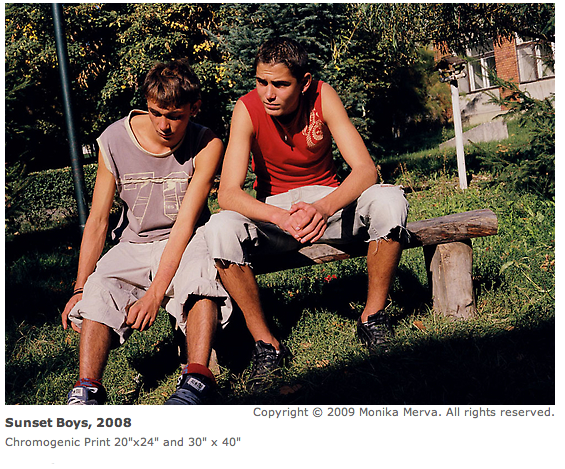

MM: No, its very loose. They have two adult guardians during the day, and in the evening, a different person would do the night shift. It wasn’t strict because they wanted the kids to self-regulate and maintain their daily schedules. They would basically just hang out. I just chalked it up to them not having enough people to keep a very close eye on them. They really spent a lot of time waiting for the next thing to happen.

KL: It seems like there is a lot of importance placed on them when they are children, but when they are adults, they are out the door.

MM: The country and the home don’t have enough resources. In the eight years I went there, they only had two men working there the entire time. The rest were retired school teachers.

KL: Can you go into a little bit more detail about the political climate in Hungary? What’s happened since communism, theres been a restructuring, right? How that’s effected the institutions set up for social welfare?

MM: When I started this project, I didn’t really pursue any contextualizing political issues, the fall of communism and the aftermath. I didn’t want them to feel I was coming in there and passing judgement on how the government was treating the children. I didn’t want to get into it in a political realm. Slowly I learned things on my own by hearing what people were discussing. This home started in the 1950s. Children were everything; they were held in such high regard. You do everything for the child. Even now that holds true. This place is government funded for them to live there. They really try and work with the kids with the limited resources they have. There’s definitely places like this that are closing down. There were 50-60 throughout Hungary, and they are closing one by one, relocating those children to homes that are still open.

KL: They are breaking up a lot of close bonds between kids.

MM: And between the kids and staff : A woman named Vera, an adult guardian, she was in her forties or fifties when I met her. She has a daughter herself. She grew up in the City of Children because her mom put her there. When she was 18, Vera left, trying to get her place in life situated. She says she felt terrible when she left, and she just wanted to go back. So she came back, and now she is there as an adult guardian.

KL: Did you photograph her at all?

MM: I did make a few portraits of her, but I chose not to include them, because I wanted to elaborate on how I felt there, the overwhelming feeling of being surrounded by kids. The adults are in the background.

KL: I think I get why you are thinking less about the social phenomenons surrounding institutions, the politics of it. This work is so much more about the strangeness that is childhood, the disorientation.

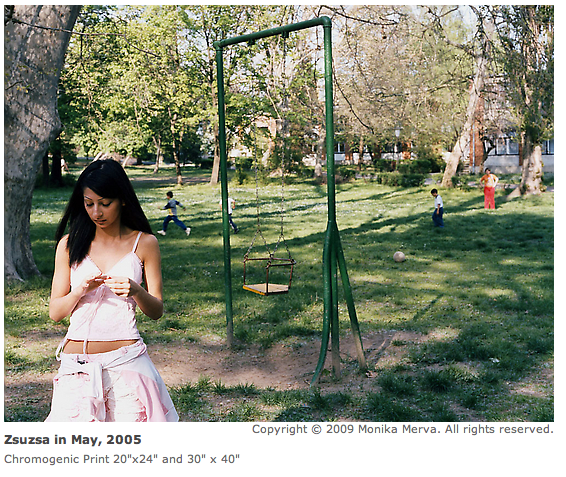

MM: I went in with no idea of what I was doing. I was very curious about this place. I’d never heard of anything like this in the US, and the home is located in a beautiful countryside. Every year that I went back I started to realize what I was photographing. The awkwardness of being a child, of being a teenager. I was photographing that waiting for something to happen, waiting to be an adult, yet on the flipside, the children have all ready been exposed to some major, adult issues. They’ve experienced so much, but they have no idea. The universality of being a child, it doesn’t matter what you have, where you are, who you have, whatever percent you are in. We are all humans, and we all experience this lonelineness of life, waiting for something to happen. We long, we love; everyone can understand that. I am very interested in trying to show the soul of a person, in finding something that will resonate with the viewer. I want to see what is not visible. I am looking for the pride and strength in anyone.

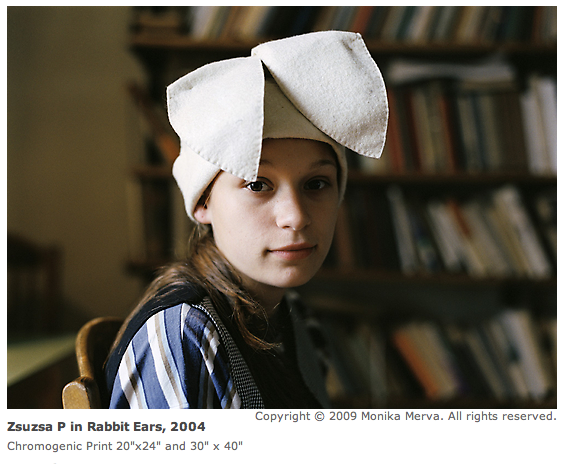

KL: Maybe that explains your interesting choice of the cover.

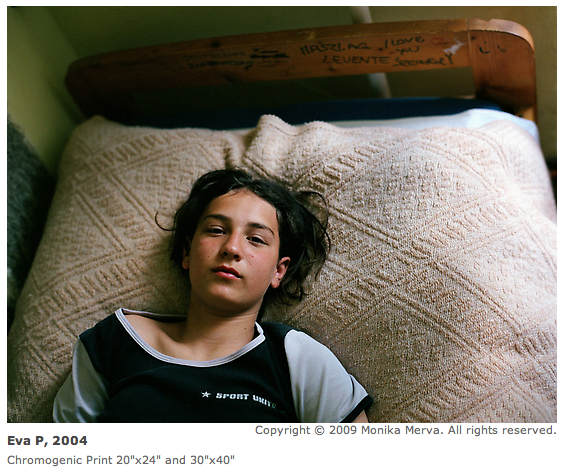

MM: We went through several options for the cover. Originally the cover photograph was going to be Eva, the androgynous looking girl lying on the bed. Its an engaging image, it gets picked for a lot of shows. But that image I would think would be deceiving for this body of work. I love the photograph we chose it because her eyes follow you. When its in the bookshop she’s looking at you all the time.

KL: I thought it was a strange choice at first. At first I was trying to find the political element in the photographs you made. The photograph of Zsuzsa P in Rabbit Ears doesn’t seem very specific--it could be anywhere. But then I look at it again, and she is there. Also, it makes sense that some of the more environmental images that you make that are so compelling wouldn’t make a good cover shot because there is no contact between the viewer and the subject. I think that photographers can easily write off this motive of looking for the soul while taking a photograph. With the evolution of the medium, and its interactions with other mediums, photography is not just about the essence of a subject. To state that as a goal, to want to do that, is now unexpected. It’s human, and gets at what you were saying about having a common denominator for the viewer to relate to. Perhaps helpful or therapeutic for the child to engage them in this type of looking as well.

MM: There are trends, I feel like many photographers are sort of mocking of everything right now. It just makes me sad. Is that work really healthy? Is that really a good thing to do?

KL: I think what is really great about your work is that you are not trying to make universal commentary about human beings, despite being universally relatable. A friend once said of my own work, "you really don't have a very positive projection for the fate of humanity, do you?" You are trying to tap into a place where we feel, by looking at and talking about a group of people. And I think the more photographers who do that, the more effective photography is as a social mechanism. There’s poignancy to different artists looking at similar phenomenons in different areas. This is not to say that there aren’t really some compelling things besides the gaze of your subjects. The objects you include in the frames are definitely along the lines of what we were talking about a bit earlier--this idea that the youth have seen so much. I think maybe many people experience childhood as incredibly violent, sensual, wanting, waiting, yearning, frustrating and then on the other hand, so utterly dopey, this state of...”whatever!” I was really struck by so much of the sensuality in the pictures, especially the photograph of Robbi. It wasn’t overt sexualization, but they aren’t the most socially harnessed photographs of children either. I was really struck by the primal energy in them.

MM: But it happened naturally.

KL: I think this is where you are scratching below the surface. I was talking about this last night with some friends-- ghost stories, horror stories are so important for children.

MM: The kids and I talked a lot about vampires

KL: The psychology of the child, he or she needs an outlet for morbidity.

MM: Fear is exciting. I think it’s groundwork for them. This morbidity is and exercise for later times, and for bigger issues.

KL: It’s ironic because at the same time the kids have all ready seen so much. I think its really think its important to continue to make work like that, to explore what it means to be a child and sensual, natural, alive, confounding the boundaries between everything adults have ordered into different places, because that helps us decompartmentalize our own worlds.

MM: Do you remember when Sally’s Mann’s Immediate Family came out. Virginia wrote that letter to the New York Times Magazine. “Why is this picture of me so bad? Why did they have to block my eyes out?”

KL: That’s even more violent. Yeah, now lets just show her body!

MM: And now she can’t even see you looking at her.

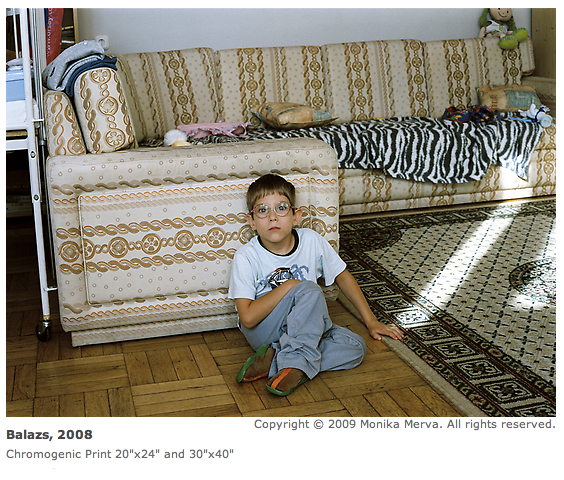

MM: This one, this boy cant walk, so he uses his arms to drag his body behind him.

He is so bright.

KL: I respect the choice to make the photograph of his eyes so prominent, then. What could have been a formal photograph of his motion, you chose to focus on his eyes.

MM: It’s who he is.

KL: Have these kids been photographed much before this, was it socialized to smile for the camera?

MM: A lot of times wed be hanging out, they’d forget the camera. Sometimes they’d, as I said, asked me to take their picture. After years of coming back, they’d understand how I make pictures.

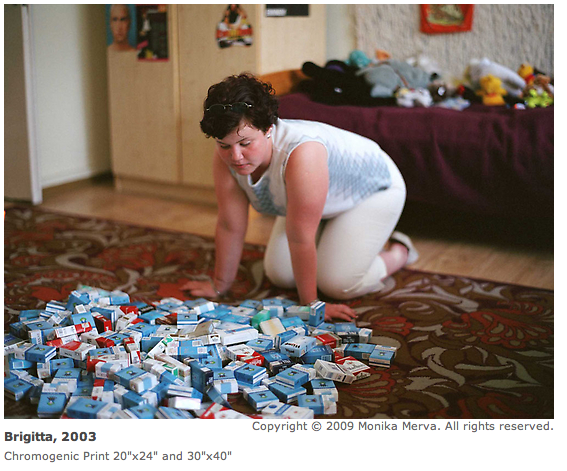

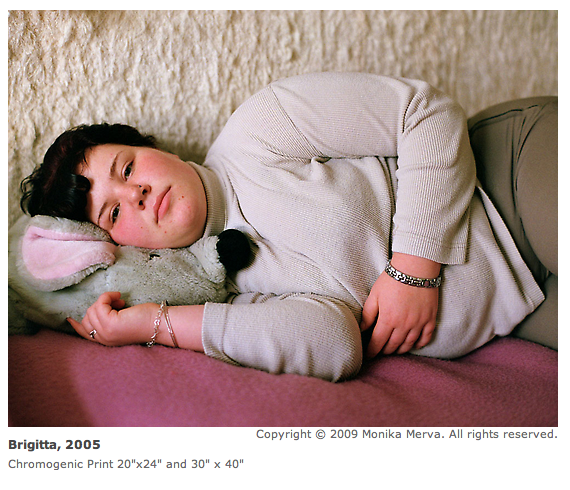

KL: Brigitta--I keep looking at this one. I can’t imagine what kind of person she must be.

MM: The first time I saw Brigitta she was counting her collected boxes of cigarettes. It’s very much an Eastern European thing to collect cigarette boxes and beer bottles. She was allowed to keep that collection. I think anyone from E. Europe knows that. After I met her, I went into the kitchen and talked with the adults, and I asked, “who is that new girl?” They’re like, “Ohhhh Brigita.” So, Brigita and I started hanging out. She wouldn’t go to school; she would sleep in late. I asked her why. She thought everything was so boring. She didn’t know what she wanted to do. She didn’t have any dreams. She said no to everything. The next year I came back, I asked if she had thought about her life. She said she was working in a pastry shop and really loved it. She was always such a hard nut, swearing, smoking her cigarettes, wearing tight clothes. She didn’t care and I loved her for everything. When she was 18, I met her boyfriend; he was 35 at the time. They are still together. She moved in with him. The following year, I came back, she had graduated and invited me to her house. She baked me cookies! That photograph of the kitten’s claws, those are her hands feeding the kitten. She had found it on the street.

KL: The hardest rocks have the softest centers and vice versa.

Did you ever have any altercations with the kids?

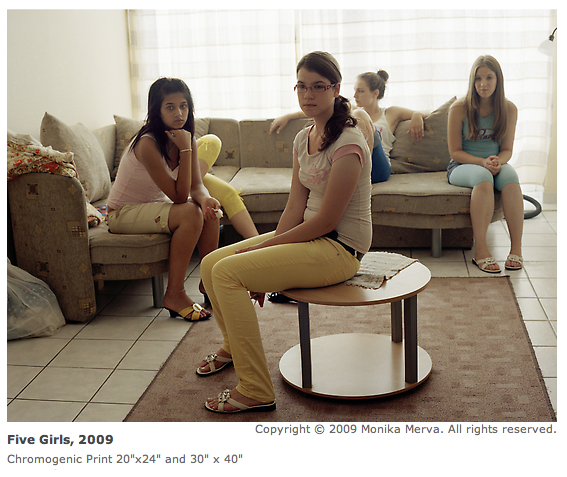

MM: Well, my last year, 2008, I knew it was going to be my last year. I knew I had to finish this book. I was going to say goodbye, and maybe get a few pictures. I walked in, and they were just like this, sitting. Eva was in the middle, with these two girls who are twins. This girl that you can’t see had always wanted me to photograph her, but I could never get a good picture of her, so its fitting that you don’t see her. So, I walked in, and I took this picture immediately before I said anything. I came in closer, put the camera down, I told them I was looking for all of them. I said, “Lets get some pictures for the last time.” And Eva says no. She said she didn’t have makeup on, didn’t like her outfit, had to do her hair. But she was always down for it.

KL: And they know how you photograph, so...

MM: Exactly. My eyes started welling up with tears because they were saying no. And the idea that this is the last time. I tried to sit and talk with them, but I was sobbing on the inside. So I left. Ava came after me, and said, “I’m sorry we didn’t let you take our picture, we just weren’t feeling it.” I told her I totally respected that, but that what made me sad, was her saying no has allowed me to really let it end. That it was a confirmation. No one had ever said no. But they are all on Facebook, so I look at their pages, and I can see how they are.

KL: I love that that is the first picture of the book. Also, your formal spatial shots are quite different.

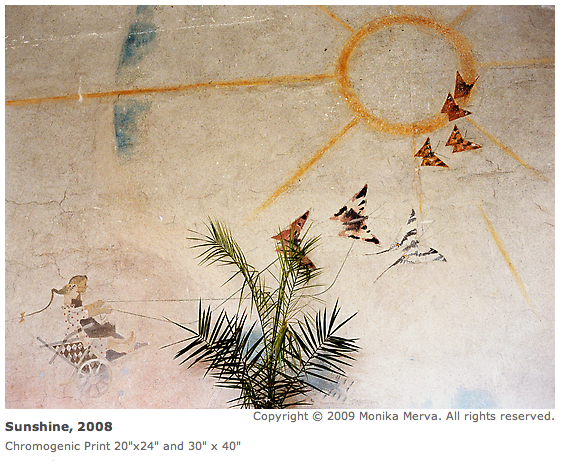

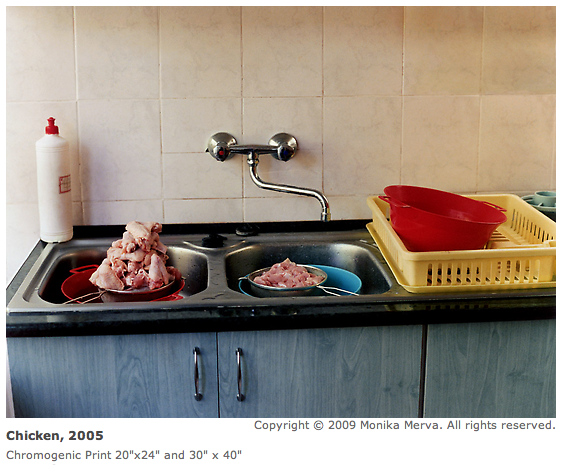

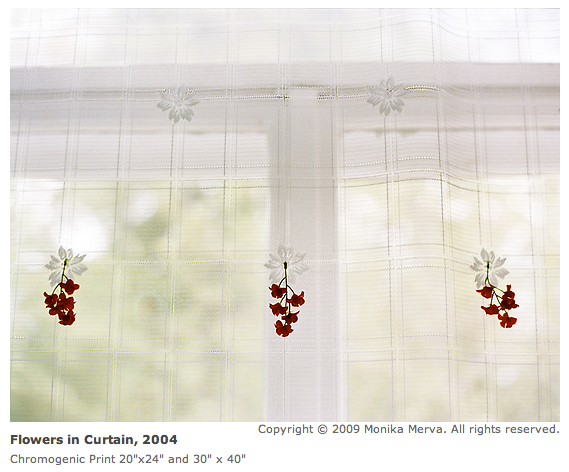

MM: While I was showing the book to people in its mid-stages, a couple of people told me that I had all the characters but I hadn’t set the stage yet. It is totally horrifying for me to take a picture without a person in it. Stilllife work scares me. When I went there I was really pushing myself to find a life behind inanimate objects. Get a soul or a presence. I wanted the objects to breathe.

KL: That makes a lot of sense given your technique in photographing people. You are successful in seeing a soul, but I’m not sure it describes anything about the space logistically. These seem to do something energetically similar to the way you make portraits of the children. There are no establishing shots.

MM: For me, the buildings were irrelevant and nondescript. They decorate their curtains with plastic flowers. I had taken pictures of the building but it didn’t do anything. It didn’t explain anything.

KL: Why did you put this photograph first in the main sequence?

MM: Its the window leading you in.

KL: It also seems like you are unveiling something secret, veiled, confounding and, as you elluded, timeless. I really appreciate you withholding of a lot of circumstances, there is no editorial time lapse, no “this is the birthday party,” “this is them sleeping.” No “day in the life.” It’s day to day, but you don’t get the stigmatization that comes along with, the “look, they do all the things we do” or trying to show every part. It’s very much about the energy of endless kids everywhere, and the endlessness of childhood.

MM: It was important not to exploit their private lives. This is intimate information. It’s not going to help for my intentions with this work, using the information in an explicit way. It was about my experience there.

KL: I love that you are able to make very strong pictures and be as ethical as you want to be about it. It’s a very difficult thing to make people feel comfortable and make interesting pictures. Its inherently violent to flatten people, to use objects to describe situations. Because objects and people aren’t the same. I think that goes back to the cover, the gaze still penetrates.

MM: I’m also very aware of, when I’m composing, what’s around the photograph, controlling what there is in the frame. I don’t want anything in the picture to be misleading.

KL: It’s funny, because sometimes it takes a little more arranging to present the most accessible truths to the viewer.

MM: Where I put myself, or what couple of things I take out makes worlds of difference.

KL: Nayland Blake talks about leaving things in, not omitting things because you think that they don’t fit into a certain realm you are trying to talk about. Let the idiosyncratic mishaps happen. I appreciate that you are coming from the opposite place, because I think what you are saying is that something in a photograph can be really misleading that is, in reality, part of something. You framing it is going to take on different meaning so you do have to omit things for the sake of the subject. I think that is one of my favorite fallacies of photography, that making unaltered pictures is the best way not to mislead.

MM: You have to be conscious of your environment, not only when you are with the camera.

KL: It teaches you about how you judge people based on other things. it teaches you to take things with a grain of salt and take them seriously all at the same time.

To see more of Merva's work, visit www.monikamerva.com