Recent Articles

-

Exhibition Review – Lothar Baumgarten at Marian Goodman Gallery

-

"The Constant Gaze" or the faith of photojournalism in Guatemala.

-

A Few Words About Me and My Work

-

Invites 1. Matt Siber

-

Invites First Post!

Categories

- #SANDY

- 2016

- 27th International Festival of Photojournalism

- Aaron Vincent Ekraim

- Africa

- AIPAD

- Almond Garden

- American Photo

- Anna Beeke

- Aperture

- Art Desks

- Artist Events

- Artist talk

- Award

- Awards

- Barmaid

- Barney Kulok

- Behold

- Best of 2015

- Book Launch

- Book release party

- book signing

- Book signings

- Book-signing

- Bryan Schutmaat

- Call for applicants

- call for entries

- Cara Phillips

- CDS

- Chicago

- ClampArt

- Closing Exhibition

- Competition

- Conservation photography

- Contests

- Cowgirl

- Critical Mass

- Cyril Christo

- Daily Mail

- Daylight

- Daylight Books

- Daylight Digital

- Daylight Digital Feature

- Daylight Photo Awards

- Daylight Project Space

- dj spooky

- Documentary Photo

- DPA

- Dread and Dreams

- E. Brady Robinson

- Eirik Johnson

- Elaine Mayes

- Elinor Carucci

- Events

- Every Breath We Drew

- exhibit

- Exhibition

- Exhibitions

- Fall 2015 Pre-launch

- Festivals

- Film Screening

- Film screenings

- Fine Art

- Flanders Gallery

- Fotobook Festival Kassel

- Françoise Callier

- From Darkroom to Daylight

- Frontline Club

- Gabriela Maj

- Gays in the Military

- george lawson gallery

- GuatePhoto

- Guatephoto Festival

- Hariban Award

- Harvey Wang

- hochbaum

- Home Sweet Home

- Huffington Post

- Hurricane Sandy

- Interview

- J.T. Leonard

- J.W. Fisher

- Janet Mason

- Jess Dugan

- Jesse Burke

- John Arsenault

- Jon Cohen

- Jon Feinstein

- Katrin Koenning

- Kuala Lumpur Photo Awards

- Kwerfeldein

- L'Oeil de la Photographie

- LA

- Landmark

- Leica Gallery

- Lenscratch

- LensCulture

- Library Journal

- Lili Holzer-Glier

- Lori Vrba

- Lucas Blalock

- Malcolm Linton

- Marie Wilkinson

- Mariette Pathy Allen

- Michael Itkoff

- Month of Photography Los Angeles

- Mother

- Multimedia

- Nancy Davidson

- New York

- New York City

- News

- NYC

- ONWARD

- Opening

- Opportunities

- Ornithological Photographs

- Out

- Party

- Philadelphia

- Photo Book

- Photo Booth

- photo-book publishing

- PhotoAlliance

- Photobooks

- Photography

- Photography Festival

- photolucida

- Poland

- portal

- Pre-Launch

- Press

- Prize

- PSPF

- Public Program

- Raleigh

- Rayko Photo Center

- Recently

- Rencontres De Bamako

- Reviews

- Robert Shults

- Rockabye

- Rubi Lebovitch

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Seeing Things Apart

- SF Cameraworks

- silver screen

- Slate

- slideluck

- Sociological Record

- Soho House

- spring 15

- Spring 2016

- Stephen Daiter Gallery

- Sylvania

- Talk

- Tama Hochbaum

- The Guardian

- The Moth Wing Diaries

- The New Yorker

- The Photo Review

- The Solas Prize

- The Superlative Light

- The Telegraph

- TIME

- Timothy Briner

- Todd Forsgren

- Tomorrow Is A Long Time

- TransCuba

- Upcoming events

- USA Today

- VICE

- Vincent Cianni

- Visa Pour L'Image

- Vogue

- We Were Here

- Wild & Precious

- Wired

- Workshop

- Zalmai

- Zofia Rydet

News

Exhibition Review – Lothar Baumgarten at Marian Goodman Gallery

Posted by Daylight Books on

Considering its themes--the ethnographic gaze, colonialist knowledge/power systems, the ineluctable battle between culture and nature--Lothar Baumgarten's show at Marian Goodman Gallery would seem to have no right to be beautiful. Almost as a rule, when one confronts this kind of exhibition it is wise to gird oneself against a coming onslaught of boring work bolstered by dry, grinding pedantry or (worse) boring work justified by way of obfuscatory warblings lifted from a litany of fashionable "post-"s (structuralism, modernism, colonialism, feminism, etc.). Nevertheless, Baumgarten's show is subtle, considered, and ravishing.

For those viewers who are familiar with Baumgarten's practice, of course, this comes as no surprise. He has been producing insightful, often gorgeous work addressing colonialism and post-colonialism, Western perceptions of the Other, and the devastation and disappearance of tribal cultures (particularly those in North and South America) since the 1960s. But familiarity with past practice proved inessential to the viewing of this show, as its two centerpiece works, The Origin of Table Manners (1971) and Fragmento Brazil (1977-2005), provided a quick (if incomplete) history lesson.

One of Baumgarten's early works, The Origin of Table Manners is a wry illustration of the way in which colonial conquerors conflated Western notions of civility with notions of the civilized as part of their alibi for domination. Inspired by a text of the same name by the structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, the work consists of a table draped in a crisp, white tablecloth and set with fine china, with porcupine quills and the feathers of large birds standing in for silverware. When it was first shown, it was installed in a tony French restaurant near Baumgarten's Paris gallery. The work certainly survives its transplantation into the gallery space, but one can only imagine, ruefully, that this original outing really knocked some socks off. Regardless, the work's main function in the show is to work in tandem with the more recently realized Fragmento Brazil, which looks at the role that cultural disparities played in colonialist domination through a slightly different lens.

Like The Origin of Table Manners, Fragmento Brazil is a kind of relic from Baumgarten's artistic past, but of a different sort. The work is made up of numerous slide projections that cycle through over five hundred images culled from points in Baumgarten's career stretching back over the past thirty years. Some of the images are black and white landscapes that Baumgarten took on a five-month walk across the Rio Caroni, Rio Uraricuera and Rio Branco regions in Venezuela and Brazil in 1977. For the most part, though, the slide images were taken from two sources, which are juxtaposed in diptychs: On the one hand, there are details from Albert Eckhout's mid-17th century paintings of Brazilian birds, which were produced in Holland after his return from a lengthy tour of the Brazilian colonies. Removed from the birds' indigenous landscape by a distance spanning oceans, Eckhout choose, strangely and, Baumgarten implies, tellingly, to paint these vibrant specimens against Dutch, rather than Brazilian, landscapes. On the other hand, there are details of drawings made by Yãnomãmi people of Venezuela and Brazil, who Baumgarten lived with for eighteen months from 1978-1980. According to Baumgarten, before his arrival the Yãnomãmi had never before used, or even seen, paper of the kind on which the drawings were ultimately rendered. As a result, the drawings might be more accurately described as transcriptions--transfers of the decorative markings used in the everyday life of the tribe onto a foreign medium.

What is most immediately striking about these pairings is the way in which the markings made by Yãnomãmi seem (admittedly, in some cases more than others) to imitate the markings on the birds in Eckhout's paintings. This could, perhaps, be billed as a minor anthropological discovery on Baumgarten's part, but what is most interesting is the way he allows the disparities between these two systems of representation to speak to their corresponding attitudes toward nature. This is not to say that the fundamental argument being presented is novel. The idea that the West tends to dominate the natural though the imposition of rational systems (such as taxonomy) that provide an illusion of control and, by extension, an alibi for destruction, while those cultures that adhere to alternate systems of thought tend to view the natural as inextricable from the warp and woof of existence, is an old one. However, this is beside the point. The reason that Baumgarten's work succeeds where comparable works fail is that Fragmento Brazil does not fall prey to the self-negating trap of the illustrative that entangles lesser work. Instead, Baumgarten allows space for the rich ambiguity of the visual, making sure that conceptual understanding, once reached, does not render the visual element tautological. And, it should be said, you don't have to be an expert in the field of conceptual art to know that this is a somewhat rare achievement.

The rest of the exhibition continues Baumgarten's investigation of the fraught relationship between nature and culture, though outside of the environs of South America. His series of photographs made in Serralves Park in Porto, Portugal from 2003-2006, collectively titled Concordance, begs to be read as an investigation of the spurious claims that manicured and stewarded park spaces have on the natural (the suggestion being that that the "concordance" between the natural as it is presented to us within the space of the park and as it exists elsewhere is largely an illusory one). Regardless of whether or not this interpretation is congruous with Baumgarten's intent, the photographs can be appreciated for their elegant understatement, which speaks of nature not in the sublime register of the vista, but in the quiet voice of the close-up, incidental view. (This is, perhaps, not insignificant as the vista painting was an artistic trope used by colonial conquerors to denote mastery and ownership.)

This quiet, humble regard of nature continues into the show's final piece, Matteawan / Fishkill Creek (2004-2008). The work is an eighty-minute sound recording made over the course of a single night in April 2007 at Denning's Point, a peninsula that juts into the Hudson River near the Southernmost boarder of Beacon, New York. Derived from previous and identically titled series of site-specific sound works that Baumgarten installed on the heavily wooded peninsula, this incarnation provides gallery-goers with a cool, dark, pillow-strewn sanctuary from the urban bedlam four floors below. Ensconced in these welcoming environs, you can contemplate the symphonic ebb and flow of nature's night sounds, punctured only occasionally by the distant clatter of human life.

It could be argued that, in and of itself, Matteawan / Fishkill Creek is little more than an elaborately conceived equivalent of those CDs of natural sounds designed to sooth the frazzled modern mind into some semblance of sleep. However, taken in the historical context of the recording site, the piece can be read as a kind of warning, which gets, I think, to the heart of Baumgarten's concerns.

As Baumgarten points out, Denning's Point was once inhabited by various Native American tribes, but was transformed at the beginning of the twentieth century into the original site of Denning's Point Brick Works (DPBW), one of the area's largest brick producers, which had a hand in building the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center. Though DPBW relocated in 1939, Denning's Point remained an industrial site until it was purchased by New York State in 1988. Since that time, nature has been allowed to reclaim the peninsula, though it remains littered with traces of it's industrial past. As a result, what we are listening to in Matteawan / Fishkill Creek is not the sound of Edenic nature, of the kind purportedly found on earnestly titled CDs in your mall's requisite nature-themed store. Rather, we are listening to the sounds of a resurgent nature, which has thrived amidst the ruins of human progress.

With this in mind, Matteawan / Fishkill Creek can be read as a kind of aural equivalent of the garden follies popular in Europe in the nineteenth century--fabricated castle ruins in the gardens of the nobility and on grounds of royal palaces that were built, at least in part, as a warning against hubris. It is a variation on this warning--that we ignore the natural and our place within its order at the risk of great peril to ourselves and others--that acts as subterranean thread connecting Baumgarten's work, whether he is in the jungles of South America, the manicured parks of Europe, or the tangled woodlands of upstate New York. If we listen closely to the sounds of Denning's Point, we can hear echoes of the wild noises that will haunt our future ruins, unless we are careful.

"The Constant Gaze" or the faith of photojournalism in Guatemala.

Posted by Daylight Books on

In a country where the sole possession a camera can jeopardise the bearer's integrity, being a photojournalist is not only an act of resistance but also one of faith. Faith in that the acknowledgement of such a situation by a wider audience will somehow improve it. In that by showing it to the world, capturing it in a still frame, it might become less real, less dangerous. As in a place far away from the witness.

This, however, certainly almost never happens. In fact, the situations and scenes that are usually depicted by the five Guatemalan photographers whose work is on display, fill the newspaper's pages as much as the citizens' nightmares with sights of death and sorrow. And yet, it has to be done. History, visual history, cannot but help us understand better; it makes us stop, reflect, and ask ourselves what is there to do about it. Perhaps it even makes us understand that society, and the other, is also our business. What usually happens is that, because of a constant bombardment of visual production from about every aspect of daily life, these images often loose their primary objective. Instead of denouncing atrocious stories, they become mere illustrations to which jaded eyes pay little or no attention.

In a small but sharp exhibition curated by Cuban specialist Valia Garzón and presented at the Centro Cultural de España in Guatemala City, photography has been removed form the newspapers' and magazines' pages and displayed together in a attempt to make of these five readings of Guatemala's past and present, a sensible account of what has been happening to this poignant Central American country over the last 30 years. Indeed, Rolando González's work refers to the civil war that thrashed the country for over three decades while Doriam Morales presents in an up-close and personal way, that violence that has, once again, taken the country to its knees over the last few years. In that way, some of the indifference that has slipped into their reading by its constant presence on the local media has been re-presented to the same daily viewers. The refreshing setting thus renewing the images' effectiveness.

Other works in the exhibition include: Jesus Alfonso's investigation on the cult to the hybrid Maximón saint, Emerson Díaz's depiction of the children that live and work in the city dump and Moisés Castillo's portrait of pain and catastrophe.

As Garzón states in her introductory essay, being a photojournalist in Guatemala requires not only technical expertise but also enough cold blood to capture a reality marked by violence and pain. Further, the images are captivating and convincing, and for these reasons, the craftsmen of the daily image deserve recognition and the acknowledgement that the truth they provide is essential to understanding a country's reality. In addition they remind us of that decisive moment on which photography once poured its foundations.

'La mirada constante' is on view through November at the Centro Cultural de España in Guatemala City, Guatemala

![Doriam Morales, From the series 'Violencia en Guatemala' [Violence in Guatemala], 2007-2008 Doriam Morales, From the series 'Violencia en Guatemala' [Violence in Guatemala], 2007-2008](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/Asesinatos_en_Guatemala2.jpg)

![Doriam Morales, From the series 'Violencia en Guatemala' [Violence in Guatemala], 2007-2008 Doriam Morales, From the series 'Violencia en Guatemala' [Violence in Guatemala], 2007-2008](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/Asesinatos_en_Guatemala17.jpg)

![Emerson Diaz, From the series 'Haces de inocencia' [Beams of Innocence], 2007 Emerson Diaz, From the series 'Haces de inocencia' [Beams of Innocence], 2007](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/SG4E0432.jpg)

![Emerson Diaz, From the series 'Haces de inocencia' [Beams of Innocence], 2007 Emerson Diaz, From the series 'Haces de inocencia' [Beams of Innocence], 2007](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/SG4E0513.jpg)

![Jesus Alfonso, From the series 'Entre la fe y el pecado' [Between Faith and Sin], 2001-2006 Jesus Alfonso, From the series 'Entre la fe y el pecado' [Between Faith and Sin], 2001-2006](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/San-Simon02_web_1.jpg)

![Jesus Alfonso, From the series 'Entre la fe y el pecado' [Between Faith and Sin], 2001-2006 Jesus Alfonso, From the series 'Entre la fe y el pecado' [Between Faith and Sin], 2001-2006](https://s3.amazonaws.com/daylightbooks.org/blog/San-Simon03_web.jpg)

A Few Words About Me and My Work

Posted by Daylight Books on

Remarkably enough, this is my first ever blog entry. Most of my friends and colleagues have their own blogs but I've resisted the pressure to start my own. When Brian Ulrich asked me to participate in this blog for Daylight, I felt that the timing was perfect. For one, I really like the idea of a specific time frame to work in. There is a clear beginning and end to the process which should end up encapsulating this short time period in a definable work. It also happens to coincide with one of the most interesting, worrisome, frightening and hopeful times in world history. I have a BA in history from The University of Vermont so history has long been an integral part of my consciousness and has helped immensely in shaping my world and artistic view.

There are several issues I would like to write about in the next fours weeks. Much of it will deal with the many thoughts I've had recently regarding art, economics and politics. I am particularly interested/concerned about how the current major changes in the world order will affect art, both on the macro scale (galleries, museums, auctions) and on the micro scale (the individual artists). As blogs are intended to be a forum, I would also like to address issues or questions that readers are thinking about.

For this first post, I thought I would begin with an introduction in order to give some context. I was born in 1972 in Chicago but I was brought up in the Boston area. I spent seven years in Burlington, VT, four of which were spent getting my BA from The University of Vermont in history and geography. The next three years were spent in Canton, NY where I worked full-time as the University Photographer at St. Lawrence University. It was these three years in a remote area of New York State that gave me the impetus to apply to MFA programs ultimately bringing me to Chicago and Columbia College in 2000. I finished my MFA in photography in 2003 and I've been working as a professional artist and educator ever since.

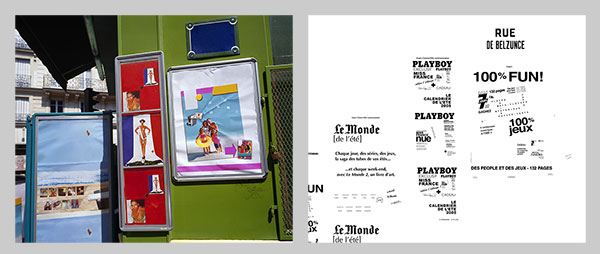

My work as a commercial photographer in my early career has greatly influenced my personal artwork. I fumbled about in graduate school for a couple of years before finally finding my voice through The Untitled Project. The project is a deconstruction of systems of communication in the public space through the use of photography and digital imaging. Each piece is comprised of two elements: one photograph with the text digitally removed from the image, and one graphical text piece that maps out the removed text on a white field. The project has helped me to explore and understand the complexity of the myriad forms of communication used to inform, influence and control large groups of people.

Untitled #35, 2006 from The Untitled Project.

Untitled #35 (image)

Untitled #35 (text)

The following project grew out of The Untitled Project as I directed my artistic attention toward text and signage. Floating Logos may not have come about if I wasn't living in the midwestern United States where the land is flat and the signs are extremely high up. The mountainous and forested landscapes of New England do not lend themselves to tall signs like these. The signs are photographed where they are (they are not super-imposed) and I have digitally removed the support structure. Series I is comprised largely of verticals with the ground left out of the image in order to emphasize the disconnect. Series II is taken in a traditional landscape format where the signs are allowed to float in context with their surroundings.

Burger King, 2004 from Floating Logos Series I

Leroy Merlin, 2006 from Floating Logos Series II

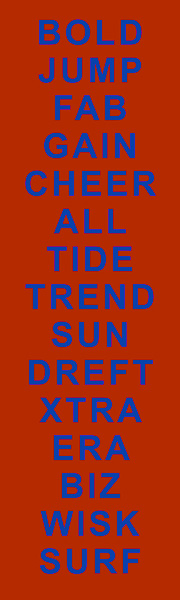

As I continued to think about visual and literary communication as well as marketing and branding, my appreciation for the power of commercial art and design grew. The Compare to… project seeks to deal directly with these issues by using generic or off-brand products found in grocery and dollar stores. By mimicking the visual elements of the major brands, these companies reinforce a set of visual signifiers that have become culturally ubiquitous. Certain colors, shapes and designs have come to signify, not only a brand, but now the product itself. The products are presented on a graphical backdrop created in Photoshop to give the aesthetic of an advertisement. Many of the products do not have brands attached to them at all giving way to the idea of the product itself being advertised rather than the abstract notion of the brand.

Mouthwash, 2006-7 from the Compare to… project.

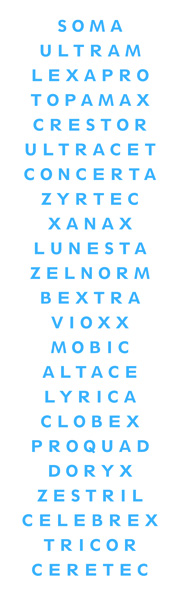

As Compare to… began to move away from photography by creating a graphical space rather than a window into 3D space, I moved a step further away from photography by working with words alone. The Lists series (working title) does something similar to Compare to… but uses the names of products rather than their packaging to help us think about the ways in which they are marketed to the public. It also becomes a somewhat nerdy study of language and semantics.

Detergent (left) and Drugs (right) from the Lists series.

This should give a good sense of where I am coming from and how I got to where I am now. My work tends to feed on itself with one project leading directly into the next. The threads are usually very clear when the work is placed in chronological context. In the coming weeks, I will make postings about some of my work in progress that should make more sense in context with the earlier projects.

I will be away for a few days this week for Thanksgiving but I will post again when I get back on Sunday or Monday.

- MS

Invites 1. Matt Siber

Posted by Daylight Books on

When I first started graduate school in Chicago, Matt Siber was one of the people I met who was pleasant enough to not only school me on the inner workings of the MFA program (he was one year ahead of me) but generous enough to lend one of his medium format cameras for several months. This began a friendship that took us photographing on road trips, traveling to lectures and exhibits together and sharing ideas and strategies. This summer I was honored to be in Matt's wedding and returned the favor by some super slick moves on the dance floor.

Matt Siber's photographs subverting advertising and consumer culture have had a profound and liberating impact on the visual world. Matt's early Untitled project separated the visual noise of our modern cities. By digitally removing the text from his landscape photographs of signs, signage and displays and recreating that same text in an diptych image, Matt empowers us to gain a footing in the ad surroundings. His investigating on the hegemonic use of the ad led him to further series Floating Logos (photographs of towering ad pole which seem to defy gravity in an all too familiar foreshadowing) and recently Compare To (product shots which act as advertisements themselves only for the no frills copies of brand name products).

Matt received his MFA from Columbia College in Chicago in 2003. He currently has a solo exhibition at the Billi Rubin Gallery in Berlin. His work is featured in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Photography. He's much more international than any of my other friends and his work is represented by the Galeria Antoni Pinyol in Reus, Spain, Galeria La Fabrica in Madrid, and Galerie f 5.6 in Munich. He has been published in ArtForum, Flash Art, Aperture and EXIT Magazine and he has received grants from the Aaron Siskind Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council.

Have questions for Matt about his work? Leave them in the comments.

Invites First Post!

Posted by Daylight Books on

Some time ago friend and photographer, Bill Sullivan and I were brainstorming about the blog and what it could and could not do. It occurred to us that far too often many were trying to impose older (non internet) forms upon the photography blogs rather than focus on what they are indeed good at. It also became clear that the blog was a wonderful way to get insight into ones artistic character. With this in mind we approached a few museums with the idea of creating a blog residency. Where for one month an artist who normally doesn't do much blogging would be invited to post. None took us up but we held the idea until Taj asked me to contribute to the Daylight blog. We thought not only could it provide accessibility to an artist who normally doesn't have that sort of broadcast., but it could be a further understanding of concepts, influences and working process.

So here's the guidelines/rules on Invites.

-

• Artists will post (at least) 5 posts. They can post as many as they like in the one month period.

-

• Readers can post questions to artists in the each monthly intro of the artist. It is up to the Invitee as to whether or not they respond to all or any of those questions. There are a few reasons for this, one being that we don't want the content of the Invitee posts to be only dictated by the readers. Another is most are simply so busy (which is why they don't have blogs themselves).

That's as complicated as it gets now on to our first Invite!