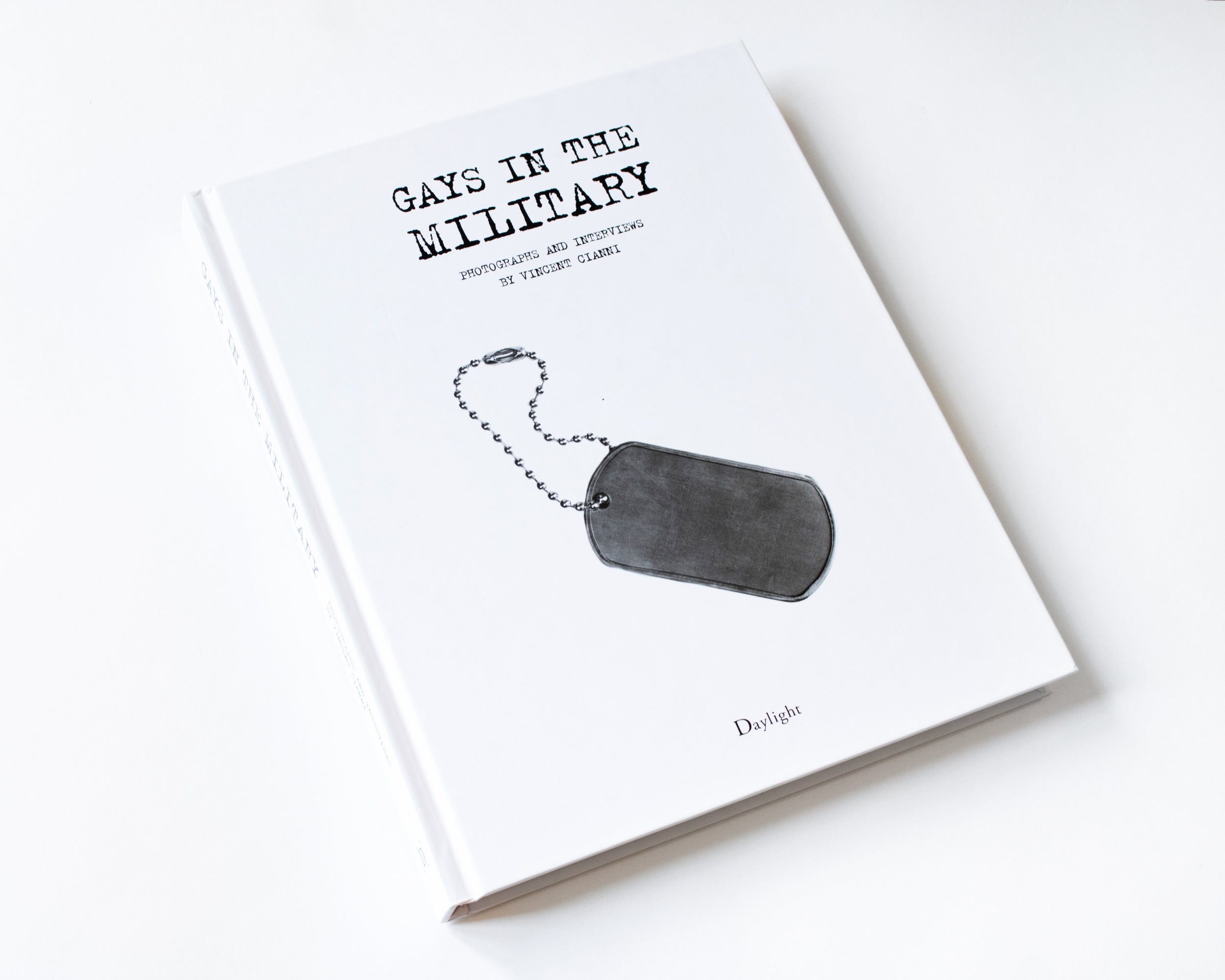

Through compelling photographs and interviews, Vincent Cianni has created a thorough and important historical record of the struggles of LGBTQ men and women in the US military. Although there has been much progress made with regard to the public embrace of alternative lifestyles and gender fluidity, cultural pockets of regressive ideals continue to exist. The US military is one such arena, and it deserves a frank and earnest reckoning from the public at large. It is our belief that Gays in the Military is an important body of work that may just help to welcome in a cultural watershed.

—The Editors

Whether I played their game or not, they’d turn me in anyway.

Travis Jackson, Montgomery, AL, 2011

Sergeant, US Army, 2004–2009

I’m fighting for my country, but my country’s not going to fight for me. If I come out, that would be grounds for termination.

Leslie Moore, Baytown, TX, 2011 Seaman E-6, US Navy, 1991–1995

Just because they can’t ask, doesn’t mean they don’t persecute.LESLIE MOORE, BAYTOWN, TX, 2011

Captain’s Cook. Honorable discharge; investigated because of speculation of homosexual relationship; chose to leave when rank was stripped

LESLIE MOORE, BAYTOWN, TX, 2011

SEAMAN E-6, US NAVY, 1991–1995

Captain’s Cook. Honorable discharge; investigated because of speculation of homosexual relationship; chose to leave when rank was stripped

Leslie Moore, Baytown, TX, 2011 Seaman E-6, US Navy, 1991–1995

My mom and dad gave me up when I was three years old. I been told that my mom was into drugs and I was addicted when I was born, that I was really small so I could fit into a chest of drawers. My grandmother said that they had beat me so bad that… I was so proper I would stand in a corner and I wouldn’t say anything. My mother died when she was about 33 years old. From the stories that I was told, she had kidney failure. My uncle told me it was heroin.

I have always been very tomboyish. I was very competitive, very headstrong, and I wouldn’t let any guy beat me. I never correlated it with being gay. Actually a rumor did start that I was gay, but it wasn’t true because I didn’t think about it. But, thinkin’ back on it, when I was with guys, it wasn’t exciting to me, if you can understand what I’m sayin’. It was good that I had a boyfriend and people saw me interacting like that. But I always thought that boys would stop me from being able to accomplish what I was trying to accomplish.

I became pregnant graduating from college. The person I was gonna have a baby by was white. He was from a prominent family. He told me he always wanted to know what it would be like to be with a black girl. I told my grandmother—I was scared to tell her—but at five months I told her. And she was like, “Well, that’s not gonna work.” For whatever reason, she wanted me to have an abortion. And that’s what I did.

The military was my get-away-free card. I couldn’t do what I wanted to do. I had a physical education degree and I went in as an E-3. I started goin’ to the gym a lot. There was a bunch o’ girls playin’ basketball and I ended up bonding with them.

All o’ them were just like me ’cause all they wanted to do was play basketball. The subject of sexuality came up and somebody asked me about being gay. And I said, “Hell no. They goin’ to hell. They goin’ to hell and they’re ‘its.’” So they didn’t open up to me with that and they left me alone with it. I just played ball. I don’t know what happened. Every once in a while I would see a girl and I’d say, “She’s cute.” And I would shake it out of my mind.

But one girl—her name was Cynthia—started hangin’ around me and was askin’ all these what-if questions. “Would you judge me if I was… attracted to females?” I said, “To each his own. That’s up to you. I have nothing to do with that.” It started clickin’ in my mind that it wasn’t botherin’ me anymore. She cornered me in the bathroom and kissed me and I didn’t pull away. “What the hell am I doing? This is wrong.” But I wanted to experience it because I guess it felt good. But in the back of my mind, I saw the preacher; I saw my father; I saw my grandmother. My grandmother would have never understood. My father would have never understood. I never came back home because I couldn’t live my life the way I wanted to.

In the military you couldn’t be out. We were still hiding ’cause we didn’t trust DADT. Just because they can’t ask, don’t mean they don’t persecute. That’s why I’m not in the military now. This was gonna be my life? It ended up not bein’ my life because the people around us complained to the master-at-arms and they ended up investigating. Although they didn’t have any proof, they had speculation. I ended up losing my rank. I lost faith, so I didn’t fight it. I got out because I was forced out.

Someone said something. I was close to this young lady but we were careful. I was too rules-and-regulations oriented. But the fact that we hung out together, and we would take our showers at the same time… They brought that up. But they didn’t see me kissing her; they didn’t see me hugging her; they didn’t see me doing anything to her. They didn’t even put the fact that I got kicked out on my DD-214 [discharge papers and separation documents]. But if you go in and look at my records, they had inappropriate relationship with a female. And since they paid me to get out, I took it.

How do you discriminate against a certain person and you are supposed to be a part of the government and you are trying to deter discrimination. That’s an oxymoron, isn’t it?

I have always been very tomboyish. I was very competitive, very headstrong, and I wouldn’t let any guy beat me. I never correlated it with being gay. Actually a rumor did start that I was gay, but it wasn’t true because I didn’t think about it. But, thinkin’ back on it, when I was with guys, it wasn’t exciting to me, if you can understand what I’m sayin’. It was good that I had a boyfriend and people saw me interacting like that. But I always thought that boys would stop me from being able to accomplish what I was trying to accomplish.

I became pregnant graduating from college. The person I was gonna have a baby by was white. He was from a prominent family. He told me he always wanted to know what it would be like to be with a black girl. I told my grandmother—I was scared to tell her—but at five months I told her. And she was like, “Well, that’s not gonna work.” For whatever reason, she wanted me to have an abortion. And that’s what I did.

The military was my get-away-free card. I couldn’t do what I wanted to do. I had a physical education degree and I went in as an E-3. I started goin’ to the gym a lot. There was a bunch o’ girls playin’ basketball and I ended up bonding with them.

All o’ them were just like me ’cause all they wanted to do was play basketball. The subject of sexuality came up and somebody asked me about being gay. And I said, “Hell no. They goin’ to hell. They goin’ to hell and they’re ‘its.’” So they didn’t open up to me with that and they left me alone with it. I just played ball. I don’t know what happened. Every once in a while I would see a girl and I’d say, “She’s cute.” And I would shake it out of my mind.

But one girl—her name was Cynthia—started hangin’ around me and was askin’ all these what-if questions. “Would you judge me if I was… attracted to females?” I said, “To each his own. That’s up to you. I have nothing to do with that.” It started clickin’ in my mind that it wasn’t botherin’ me anymore. She cornered me in the bathroom and kissed me and I didn’t pull away. “What the hell am I doing? This is wrong.” But I wanted to experience it because I guess it felt good. But in the back of my mind, I saw the preacher; I saw my father; I saw my grandmother. My grandmother would have never understood. My father would have never understood. I never came back home because I couldn’t live my life the way I wanted to.

In the military you couldn’t be out. We were still hiding ’cause we didn’t trust DADT. Just because they can’t ask, don’t mean they don’t persecute. That’s why I’m not in the military now. This was gonna be my life? It ended up not bein’ my life because the people around us complained to the master-at-arms and they ended up investigating. Although they didn’t have any proof, they had speculation. I ended up losing my rank. I lost faith, so I didn’t fight it. I got out because I was forced out.

Someone said something. I was close to this young lady but we were careful. I was too rules-and-regulations oriented. But the fact that we hung out together, and we would take our showers at the same time… They brought that up. But they didn’t see me kissing her; they didn’t see me hugging her; they didn’t see me doing anything to her. They didn’t even put the fact that I got kicked out on my DD-214 [discharge papers and separation documents]. But if you go in and look at my records, they had inappropriate relationship with a female. And since they paid me to get out, I took it.

How do you discriminate against a certain person and you are supposed to be a part of the government and you are trying to deter discrimination. That’s an oxymoron, isn’t it?

I could fag bash just as good as anybody else. It almost became a survival tool, because if I did that, then how could I be gay?

Nancy Russell, San Antonio, TX, 2010

Lieutenant Colonel, US Army, 1962–1982

That was the hard part, the separations. You never did get to choose in the military…One day you would be with somebody and the next thing you know you were going your separate ways.

Katherine Miller, New Haven, CT 2010

US Army Cadet, West Point Academy, resigned appointment

I knew in my heart that the policy was wrong, but I was going to adhere to it because that was my job.

Don Bramer, Washington, DC, 2011

Lieutenant O-3, US Navy, 2002–Present

I’m like everybody else. I have a job. I have a career. I want the same things: a home, family, everything else. I’m not any different.

DON BRAMER, WASHINGTON, DC, 2011, LIEUTENANT O-3, US NAVY, 2002–PRESENT

Don Bramer, Washington, DC, 2011 Lieutenant O-3, US Navy, 2002–Present

I deploy with the Special Warfare Community as an intelligence officer. My job is sitting down with the bad guy and having a conversation to gather information. You learn to talk to people, and you learn how to engage and participate in all sorts of cultures. I found hiding my own sexuality prepped me for this. “OK, you need to learn to be somebody else? Great! I’ve been doing that all my life.”

I’m like everybody else. I have a job. I have a career. I want the same things: a home, family, everything else. I’m not any different. I never did let being gay become an issue, because I think that who I love really doesn’t play any part in the rest of my life. While I did not agree with Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, that was a sacrifice that I was willing to make. If so many other people can sacrifice so much, including their lives, then I can sacrifice this part of me that identified as being gay. But it really touched home with me when I was deployed. I felt like I was living three lives. There was me, there was the person I had to be in order to conform within the military, and then now, all of a sudden, because of my career path, I had to create another identity. You come back and it’s harder to figure out who the fuck you are.

Through two of those deployments, I was in a relationship. A lot of people [were] getting discharged, so my partner and I learned our own coding system. We would write, but we never signed a letter. We developed symbols that only we knew what they meant. You can’t share this most intimate part of yourself with friends who you’re extremely close to and would die for. And they’re talking about their plans. “Hey, when we get home, are you going on vacation? Are you going to do this?” And they’re talking about their wives, their kids, families, and you can’t do that. You learn how to refer to your partner in opposite pronouns. He becomes she. You create a name for them because you want to share these things about your life, but you got to protect yourself and protect that person. Michael now is Michelle. My partner had it easy; instead of being Don, I became Dawn.

In a lot of ways I blame the policy for ending my relationship. [My partner] would not go to therapy, because he was so afraid of anything that would come out during his sessions would be releasable to his chain of command, and that would end his career. I saw a stellar soldier deteriorate before my eyes. Quit working out. Lost all intimacy. Because of the stigma associated with [PTSD] and because of his sexuality, his coping mechanism was through food and acting out sexually to a point where it caused him to become [HIV] positive, which led to our breakup. After that, I had another deployment, and I came back and had the same, similar thought process. I don’t want to seek military means because I don’t want to ruin my career. I don’t want it on my clearance. But I knew that it was affecting my life. I knew that it was affecting my relationship with my friends and my peers and other dating relationships I tried to get into.

Because you’ve lived so many years in other identities, you’ve got this internal struggle. It was just building up, building up, building up…A lot of it is still a blur. I came home one night, sat on the front porch, fired up a cigar and made a drink. I basically killed a bottle of bourbon. I sent a friend of mine a text: “You probably need to come over.” I was checking out. A lot of the guilt for things you do in combat all surfaced. I can’t have a great relationship and I have nightmares and demons. “I’m done, I’m tired. I just can’t do this.” He tackled me and took every weapon I had away from me. The next day, I called one of my best friends. Through his help, I found somebody who helped people come out of their ulterior identity and had dealt with gay issues before for law enforcement. So, we began that very painful process. He had a guerrilla-style therapy; for six months it was three or four nights a week, and most nights were with written homework. My last session was the week, before my commissioning ceremony. I went in and said I got my speech done, so I read it to him and he just looked at me and smiled and said, “This is your graduation ceremony. We’re done.” Through that I started doing my volunteer work with homeless veterans, helping them with their PTSD issues; that was my way of taking the bad part and doing something good with it.

I’m like everybody else. I have a job. I have a career. I want the same things: a home, family, everything else. I’m not any different. I never did let being gay become an issue, because I think that who I love really doesn’t play any part in the rest of my life. While I did not agree with Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, that was a sacrifice that I was willing to make. If so many other people can sacrifice so much, including their lives, then I can sacrifice this part of me that identified as being gay. But it really touched home with me when I was deployed. I felt like I was living three lives. There was me, there was the person I had to be in order to conform within the military, and then now, all of a sudden, because of my career path, I had to create another identity. You come back and it’s harder to figure out who the fuck you are.

Through two of those deployments, I was in a relationship. A lot of people [were] getting discharged, so my partner and I learned our own coding system. We would write, but we never signed a letter. We developed symbols that only we knew what they meant. You can’t share this most intimate part of yourself with friends who you’re extremely close to and would die for. And they’re talking about their plans. “Hey, when we get home, are you going on vacation? Are you going to do this?” And they’re talking about their wives, their kids, families, and you can’t do that. You learn how to refer to your partner in opposite pronouns. He becomes she. You create a name for them because you want to share these things about your life, but you got to protect yourself and protect that person. Michael now is Michelle. My partner had it easy; instead of being Don, I became Dawn.

In a lot of ways I blame the policy for ending my relationship. [My partner] would not go to therapy, because he was so afraid of anything that would come out during his sessions would be releasable to his chain of command, and that would end his career. I saw a stellar soldier deteriorate before my eyes. Quit working out. Lost all intimacy. Because of the stigma associated with [PTSD] and because of his sexuality, his coping mechanism was through food and acting out sexually to a point where it caused him to become [HIV] positive, which led to our breakup. After that, I had another deployment, and I came back and had the same, similar thought process. I don’t want to seek military means because I don’t want to ruin my career. I don’t want it on my clearance. But I knew that it was affecting my life. I knew that it was affecting my relationship with my friends and my peers and other dating relationships I tried to get into.

Because you’ve lived so many years in other identities, you’ve got this internal struggle. It was just building up, building up, building up…A lot of it is still a blur. I came home one night, sat on the front porch, fired up a cigar and made a drink. I basically killed a bottle of bourbon. I sent a friend of mine a text: “You probably need to come over.” I was checking out. A lot of the guilt for things you do in combat all surfaced. I can’t have a great relationship and I have nightmares and demons. “I’m done, I’m tired. I just can’t do this.” He tackled me and took every weapon I had away from me. The next day, I called one of my best friends. Through his help, I found somebody who helped people come out of their ulterior identity and had dealt with gay issues before for law enforcement. So, we began that very painful process. He had a guerrilla-style therapy; for six months it was three or four nights a week, and most nights were with written homework. My last session was the week, before my commissioning ceremony. I went in and said I got my speech done, so I read it to him and he just looked at me and smiled and said, “This is your graduation ceremony. We’re done.” Through that I started doing my volunteer work with homeless veterans, helping them with their PTSD issues; that was my way of taking the bad part and doing something good with it.

Joanna Gasca, Surprise, AZ, 2012

Senior Master Sergeant E-5, US Air Force, 1983–1987 and 2000–Present, and

US Air Force Reserve, 1987–2000

There was a time when I would lie, then one day I said screw that…I’m doing my job, sucker, just leave me alone.

Anthony Loverde, Little Rock, AR, 2012

Staff Sergeant, US Air Force, 2001–Present

I came out to my command and told them I wasn’t going to lie anymore and that my crew deserved honesty. I deserved honesty.

JSB and Harry Pulver, Scranton, PA, 2010

(active duty, US Army Reserves)

The military is a part of my life; it’s not my entire life. Same with my sexuality; it’s a part of my life but it doesn’t define everything about me.

I thought it would be easy to hide, because I had been hiding it already. I hid for years.

PAUL GOERCKE, SAN FRANCISCO, CA, 2012, MESSMAN/STAFF OFFICER, US MERCHANT MARINES, 1944–1945

I was born October 27, 1926, four days from Halloween! I did not follow patterns of everybody else in terms of maturing and the usual things of childhood. I became pianist of the church when I was 10. I wrote arrangements and picked up evangelistic-style playing. There was no evidence about gay life; nobody ever talked about it in the family, which was very typical. We were very “churched” and we read the Bible, so we must have come across Deuteronomy and other places that take up this subject.

When I became 18 I would’ve been drafted, so I chose the Merchant Marines. During the war, we landed the Marines in the Ie-Shima invasion [off the coast of Okinawa]. It was a magnificent sight of flares and planes, and all in the air, and some in flames. It was a horrible thing, fireworks in real life rather than something seen on July the Fourth. I don’t understand why the captain didn’t bring a chaplain; with 1,500 guys, you’re bound to have at least one chaplain there, if not a dozen or so. Anyway, I knew I was attracted to guys in a way, but I didn’t put the dots together and figure it out.

All during the time in the service, I was on two troopships; they were both Liberty ships, and one of them was the James King, and on that one, we went from San Francisco up to Humboldt County and picked up a load of lumber. This was now 1945. In April, we were back in Okinawa, but this time not fighting a battle; the war was just about over. We ended up in Tokyo Bay three weeks after the signing of the surrender. We went up to Hokkaido and dropped all the lumber off there so [the Japanese] could rebuild. Then we came back to Tokyo Bay, and during that time I courted with GI Gospel Hour. I was 22 when I was out of the service.

I went back to Japan in ’49 and worked there three years with ex-GIs. It was during that time that I was getting involved in various things because of all those GIs! I played for the Youth for Christ for all of Asia. They had a truck to travel on. We held rallies in big auditoriums and these mass outdoor rallies, because so many Japanese lived outside. All the places were so bombed. But the thing that was so shocking was there were these two couples; they were Baptist missionaries. One of the wives played the piano, and I played the organ, a Hammond organ, of all things. Anyway, I was moving on, looking at this and that, and I discovered that in the Emperor’s Palace area, there was this national park. And there was a men’s room. I went in there once or twice to look around, and all these GIs were in there carrying on! And the two male missionaries were there! Now it’s a fusion of sex and religion! You had to realize that the Roman Catholics are loaded with gays, especially the ones that go off into these retreats and live on the sands or something.

Joseph Rocha, Washington, DC, 2010

Petty Officer Third Class, US Navy, 2004–2007

Joseph Rocha, Washington, DC, 2010 Petty Officer Third Class, US Navy, 2004–2007 Master-at-Arms, K-9 Unit Dog Handler. Honorable discharge after coming out to his commanding officer; suffers PTSD from years of abuse, hazing, and humiliation

Victor Fehrenbach, Boise, ID, 2011

Lieutenant Colonel, US Air Force, 1991–2011

They took everything. They took my flying, they took my career, they took my retirement.

Ray Chism, Bronx, NY, 2010

Airman Second Class, US Air Force, 1963–1967

Private Second Class, US Army Reserve, 1980–1984

RAY CHISM, BRONX, NY, 2010

AIRMAN SECOND CLASS, US AIR FORCE,

1963–1967

PRIVATE SECOND CLASS, US ARMY RESERVE,

1980–1984

Aircraft Mechanic/Clerical. Other than honorable discharge, suspicion of homosexuality; prevented from reenlisting

Ray Chism, Bronx, NY, 2010 Airman Second Class, US Air Force, 1963–1967 Private Second Class, US Army Reserve, 1980–1984

I have been gay all my life. I realized that this was something that I held within myself. I didn’t tell anybody what I was feeling; I just kept it inside all through high school and till my freshman year in college. I was confused at that time. I wrote the dean of Morehouse College a personal letter. I didn’t feel that I needed to cut my hair—I felt that my hair bein’ long didn’t necessarily indicate that I was homosexual and that I was having feelings of being homosexual—and [asked] if he would give me enlightenment how it would affect my term in school. I didn’t get any kind of response from him.

I was there from ’61 to ’62. The college courses proved to be much more difficult than what I was accustomed to in high school. My average was usually 90s and 100s on work that I turned in. But they fell below the average, so I couldn’t go back my sophomore year. I had hopes of studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. I enlisted in the Air Force because of a old wives’ tale—if you’re not a man, the military service will make you a man. It was September 23rd of 1963. I was in Texas—Lackland Air Force Base—when the news came [just two months later] that the president had been shot.

I didn’t answer the question [on homosexuality] correctly. I said no. I knew I would be refused entry if I answered correctly. It sort of bothered me because I was raised Southern Baptist in the church. I was a firm believer that God would punish you if you lied. But I felt that it was a means to an end and that God understood. I felt bad about it in a way.

In basic training, you had these challenges; you had to swing on these ropes. “What? Are you a girl? You can’t do this? Come on man! You can do this!” If you missed a certain challenge, you got set back and you had to do the thing all over again. I went through it without any setbacks. I was proud of myself. I was trying to come to a conclusion that this is the way I was. “This the way you gonna be until you die.” It’s not something that you can do—change your sexuality, change your feelings about men—by the things that you do. That was the thought I had. If I do enough masculine things, then my sexuality would probably automatically change. I would be masculine or oriented masculine.

I was at Lackland for about two years as far as I remember. Then I was transferred to the technical school for aircraft mechanics. I hated it. I wanted the clerical section, but I didn’t qualify. After being trained as a mechanic and working for a while on the flight line, I spent my last year in Thailand. About eight months before I left Thailand, I cross-trained into administrative. I was filling out discharge papers for airmen that were coming out. I left the mechanical field entirely, but I was discharged under the Mechanical MOS [Military Occupation Specialties, his job description].

I had a roommate; we understood each other. It was after we went to tech school and we were working as mechanics. I would pull a KP [kitchen patrol] for him and he would help me do the mechanical things on the aircraft that I couldn’t do too well. We had strong feelings for each other. He was married on the outside and he went back to his wife and child. But we were close while we were in the military. We were very well aware that we couldn’t carry out our feelings for each other any further than what we were doing there in the barracks. When I was transferred to Thailand, he went to Ohio. When losing your mate, you miss having the person around and having somebody to understand you nearby. We had planned to meet after we got out. He was from St. Louis, Missouri, and I never went to St. Louis after I got out of the service. He said, “Look me up.” I never pursued it. The only thing I have left is a picture of him that I still have in my album, my photograph album. I worked on different jobs from ’67 to ’75 in Georgia. I came to New York in ’75. I read an article about Greenwich Village and the things that the gays were doin’. I felt I wanted to come because of that. I was going with a guy that had an old car and he drove me from Atlanta to New York. We had some excursions in that car. It broke down once or twice while we were on the route. But it was enjoyable. It was a thing I’ll never forget.

My uncle lived in Harlem by himself. I didn’t know exactly where he lived, but I found him. I lived with him for several years. My uncle had a friend—they had been friends for a while. We were attracted to each other. I stayed with him in an apartment and then later on, I got my own apartment. We were pretty close to each other. As a matter of fact, he was married and had kids. His kids knew that he was gay and so did his wife. It was kind of a peculiar situation. We were friends until he passed away in ’83.

I went in the Army Reserve in 1980 to 1984. I missed the camaraderie, being in an organization and working. I wanted the compensation for being enlisted too. I didn’t have much of a job. I enjoyed the reserves while I was in, but I feel that I was wronged. They didn’t allow me to reenlist because they found out that I was living with my uncle, which wasn’t really a reason to indicate that I was gay. They had ways of checking up on people. Somehow they found out. They gave me a less-than-honorable discharge.

I wouldn’t say that I’m angry as such. I just feel that there’s a strong need for adjustment for the military. Those rules and regulations that they have are old and archaic, and they should change and come up to date and accept people as people are. I have in the back of my mind that one day I’ll write a book. I haven’t written anything yet, but I want to let out some of the things that I have accomplished over the years. I feel that people should know all the things that I’ve learned that would be of interest to other people.

I was there from ’61 to ’62. The college courses proved to be much more difficult than what I was accustomed to in high school. My average was usually 90s and 100s on work that I turned in. But they fell below the average, so I couldn’t go back my sophomore year. I had hopes of studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. I enlisted in the Air Force because of a old wives’ tale—if you’re not a man, the military service will make you a man. It was September 23rd of 1963. I was in Texas—Lackland Air Force Base—when the news came [just two months later] that the president had been shot.

I didn’t answer the question [on homosexuality] correctly. I said no. I knew I would be refused entry if I answered correctly. It sort of bothered me because I was raised Southern Baptist in the church. I was a firm believer that God would punish you if you lied. But I felt that it was a means to an end and that God understood. I felt bad about it in a way.

In basic training, you had these challenges; you had to swing on these ropes. “What? Are you a girl? You can’t do this? Come on man! You can do this!” If you missed a certain challenge, you got set back and you had to do the thing all over again. I went through it without any setbacks. I was proud of myself. I was trying to come to a conclusion that this is the way I was. “This the way you gonna be until you die.” It’s not something that you can do—change your sexuality, change your feelings about men—by the things that you do. That was the thought I had. If I do enough masculine things, then my sexuality would probably automatically change. I would be masculine or oriented masculine.

I was at Lackland for about two years as far as I remember. Then I was transferred to the technical school for aircraft mechanics. I hated it. I wanted the clerical section, but I didn’t qualify. After being trained as a mechanic and working for a while on the flight line, I spent my last year in Thailand. About eight months before I left Thailand, I cross-trained into administrative. I was filling out discharge papers for airmen that were coming out. I left the mechanical field entirely, but I was discharged under the Mechanical MOS [Military Occupation Specialties, his job description].

I had a roommate; we understood each other. It was after we went to tech school and we were working as mechanics. I would pull a KP [kitchen patrol] for him and he would help me do the mechanical things on the aircraft that I couldn’t do too well. We had strong feelings for each other. He was married on the outside and he went back to his wife and child. But we were close while we were in the military. We were very well aware that we couldn’t carry out our feelings for each other any further than what we were doing there in the barracks. When I was transferred to Thailand, he went to Ohio. When losing your mate, you miss having the person around and having somebody to understand you nearby. We had planned to meet after we got out. He was from St. Louis, Missouri, and I never went to St. Louis after I got out of the service. He said, “Look me up.” I never pursued it. The only thing I have left is a picture of him that I still have in my album, my photograph album. I worked on different jobs from ’67 to ’75 in Georgia. I came to New York in ’75. I read an article about Greenwich Village and the things that the gays were doin’. I felt I wanted to come because of that. I was going with a guy that had an old car and he drove me from Atlanta to New York. We had some excursions in that car. It broke down once or twice while we were on the route. But it was enjoyable. It was a thing I’ll never forget.

My uncle lived in Harlem by himself. I didn’t know exactly where he lived, but I found him. I lived with him for several years. My uncle had a friend—they had been friends for a while. We were attracted to each other. I stayed with him in an apartment and then later on, I got my own apartment. We were pretty close to each other. As a matter of fact, he was married and had kids. His kids knew that he was gay and so did his wife. It was kind of a peculiar situation. We were friends until he passed away in ’83.

I went in the Army Reserve in 1980 to 1984. I missed the camaraderie, being in an organization and working. I wanted the compensation for being enlisted too. I didn’t have much of a job. I enjoyed the reserves while I was in, but I feel that I was wronged. They didn’t allow me to reenlist because they found out that I was living with my uncle, which wasn’t really a reason to indicate that I was gay. They had ways of checking up on people. Somehow they found out. They gave me a less-than-honorable discharge.

I wouldn’t say that I’m angry as such. I just feel that there’s a strong need for adjustment for the military. Those rules and regulations that they have are old and archaic, and they should change and come up to date and accept people as people are. I have in the back of my mind that one day I’ll write a book. I haven’t written anything yet, but I want to let out some of the things that I have accomplished over the years. I feel that people should know all the things that I’ve learned that would be of interest to other people.

Nathanael Bodon, Marlboro, NY, 2009

Private, US Army Reserves, discharged under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

It’s the soldier’s responsibility to prove that they are not gay. What does that entail? How do you prove your sexuality?

Michael Almy, Washington, DC, 2010

Major, US Air Force, discharged under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

I maintain to this day that the Air Force violated DADT by searching the emails. And yet no one else was held accountable for that. No one else was punished.

Marquell Smith, Chicago, IL , 2010

Sergeant, US Marine Corps, discharged under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

When I walked off of that base, I cried. I cried not because I was sad; I cried because I finally felt what freedom was like.

YVONNE BISBEE, ATASCOSA, TX, 2012

TECHNICAL SERGEANT, US AIR FORCE,

1979–1999

SIGINT Analyst, Intelligence Analyst. Retired; repeatedly threatened with being outed throughout military career; suffers anxiety and panic attacks

My mother was physically, verbally, and mentally abusive. I fought tooth and nail every step of the way, but I learned at a very young age that it wasn’t me who was the problem. That protected me. I’ve always been strong-willed. I don’t think she liked the defiance she saw in me. My stepdad was the buffer between us, but when I came out to him, he would have nothing to do with me.

I lived just outside of Erie, Pennsylvania. I knew I was different, and I did not want to be stuck in a small town for the rest of my life. I had a partial scholarship to a local school to play volleyball and I talked to my mother about it. They couldn’t afford to send me to college, so she took me to the Air Force Recruiting office: “My daughter wants to enlist—sign her up!” I enlisted with delayed entry in December of ’78. I was pissed at my mother, but it turned out to be one of the best things she ever did. It opened the world to me.

I was 17, barely out of high school, and I fell in love for the first time with a woman. I met her in tech school, and it was an instant attraction for both of us. My stomach was in knots when she would come around. She made me realize that is how I want to live the rest of my life, but I knew enough not to show it, because my career was important to me and I wasn’t going to jeopardize what I could become for who I was out of uniform.

My older sister and I were never close; there was always a mutual dislike. She entered the Air Force in 1978, a year before I did. My first job was a Morse systems operator. That was also her career field. The intel world is small and her presence in it haunted me my entire career. I cross-trained and became a SIGINT [signals intelligence] analyst before being sent to RAF Chicksands, England, where she was already stationed. A few days after I arrived, we were driving onto base and she pointed out the female security police on duty and told me to stay away from Mr. Man—she referred to lesbians as Mr. Man.

I never told my sister I was gay; we never discussed my personal life. I’m not sure when she actually found out, but with that knowledge came power over me. At first it was comments like, “Are you seeing Mr. Man?” Then it was not being invited to my nephew’s school events, to not being invited to birthdays and holidays. If I pushed her about it, she would say, “You know I could end your career with one phone call” or “I’m sure OSI would love to know you’re gay.”

I never doubted for a minute that she would make that phone call. It got to the point where I quit trying to be a member of my own family. I was afraid she’d go through with her threats and my career would be over. I was more afraid of the fallout to my friends. The Air Force loved getting other gays simply through guilt by association. It was one thing if I lost my career, but I wasn’t about to see it happen to my friends. I finally quit being afraid of losing my career on the 21st of May 1999, the day I retired.

My anxiety/panic attacks began in the mid ’80s as a result of living two lies, or lives: I couldn’t talk about my job at home and I sure as hell couldn’t talk about my personal life at work. I started to feel invisible. At first the attacks were minor. They would come out of nowhere. Large crowds of people would cause them; movies at the theater became a thing of the past. Knowing I had to be outside in formation would guarantee one. Trying to explain to someone what was going on made others look at me like I was crazy, so I quit explaining and suffered through them. I drank to avoid the attacks and mask the symptoms.

My first major attack landed me at the ER in the summer of 1998. I thought I was having a heart attack. After hours of tests the doctor came in and told me I had a severe anxiety attack. There were many contributing stressors: caring for my mother after she was diagnosed with a brain tumor, I was about to have major surgery myself, and looking at less than a year left until retirement and not knowing what I wanted to do with the rest of my life, plus the fact that I was still invisible. It took a while, but I quit drinking and now take medication to mask the symptoms.

For 30 years I lied about who I was; 20 years in the Air Force and 10 years in the corporate world. Gays didn’t fit into the grand scheme of how things should be. Some of the best analysts and linguists I’ve ever worked with are gay. We have gone places. We have done things. And we have done it twice as well, because we’re dedicated to the job and mission. We had to prove to our straight counterparts that we were just as good as, if not better than, they were. It’s always been a challenge. Lesbians and gays in the military have always been more motivated to doing a better job. I don’t know if it’s just a sense of pride in ourselves, or if we’re just overachievers.