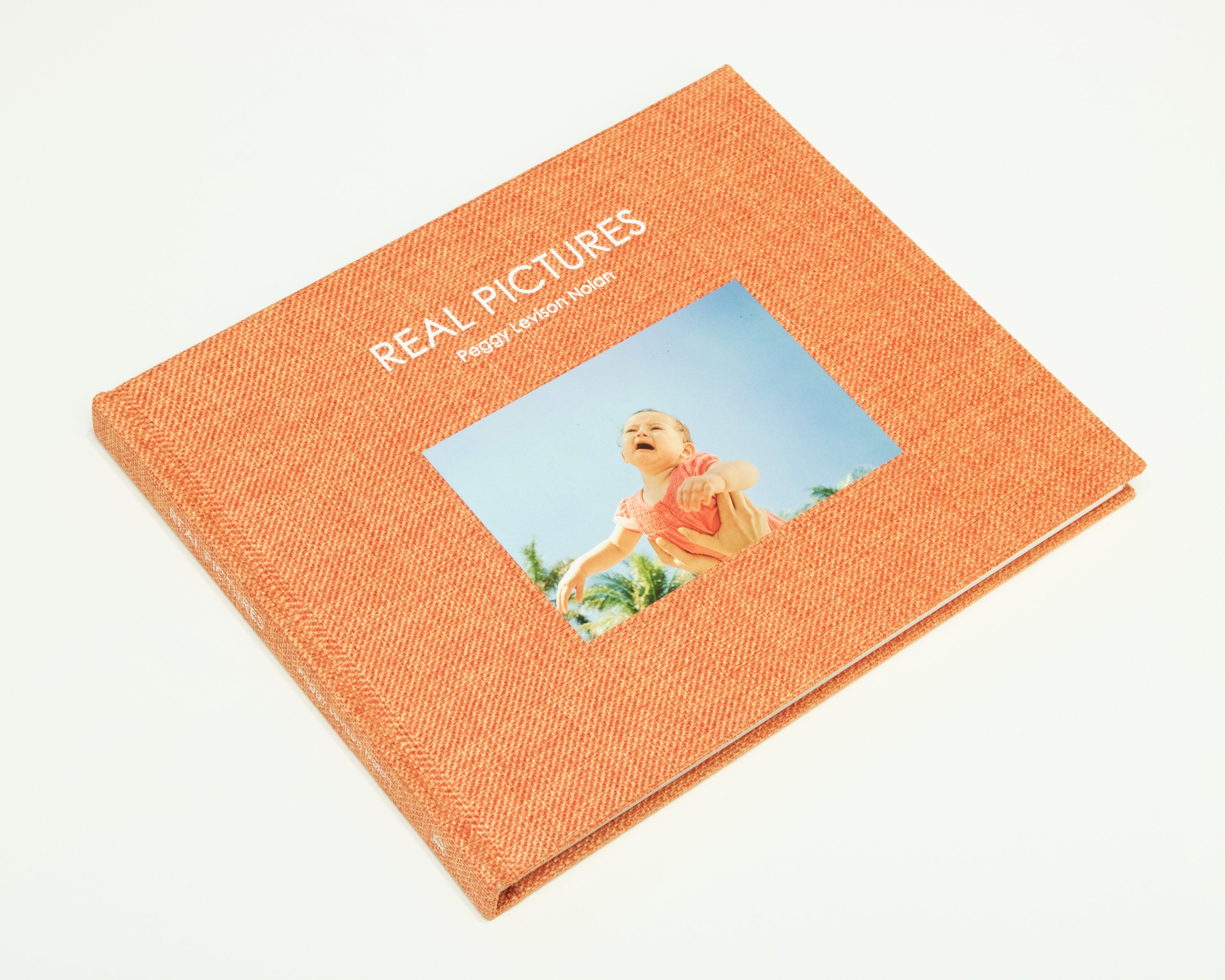

MODEL CHILD

ABNER NOLANFor the last 34 years or so I have been the son of a photographer. My siblings and I are part of a long tradition of progeny who stand more or less still before the camera, in the service of record-keeping for posterity—and, less often, in the service of art.

For generations now, children have performed the dreams of their parents, dutifully posing at birthdays and graduations, smiling and sitting up straight—all in a small effort to keep the family together, at least in pictures. In the early

1980s my grandfather gave my mother a 35mm Olympus camera, in the pointed expectation that he would see pictures of his seven (smiling, happy, well-adjusted) grandchildren.

1980s my grandfather gave my mother a 35mm Olympus camera, in the pointed expectation that he would see pictures of his seven (smiling, happy, well-adjusted) grandchildren.

For a few years the pictures followed, with drugstore-printed color snapshots stuck into cheap frames and glued into family albums. After a few night classes and my mother’s introduction by a local librarian to the work of artists such as Walker Evans and Garry Winogrand, our modest detached laundry room was commandeered and outfitted as a small black-andwhite darkroom, and my mother’s ambitions for the pictures grew apace.

For most of the time since, she has pointed her camera in the direction of us. We are the performing, temperamental, rebellious, accommodating, often bored people appearing as the players in the dramas at the center of her work.

The pictures are unsparing in their description of our sprawling, unkempt life, from the bad fashion decisions and dirty apartments to an endless parade of ex-boyfriends and ex-girlfriends. Nothing was really off-limits, and we were (are) mostly willing participants.

We are willing because of the pictures. After a few years of being subjects, the benefits of beautiful hindsight was too intoxicating to resist. So we excused the endless intrusions into our personal lives and more or less obeyed the abrupt commands of “don’t move.”

We all realized the gift of our mother’s close watching—that the beautiful, richly described pictures of our everyday lives created an idealized auxiliary to the messiness of actual life. More important, the pictures reaffirm our connections to each other through the kind of carefully crafted fiction that comes from a mother (literally) looking after her children.

After more than two decades of struggling to make art while cobbling together lunch money and tending to the needs of teenage bodies, she saw the last of us, my youngest sister, leave the house. In the wake of this absence my mother’s pictures changed. The fleeting mini-dramas gave way to something quieter—a more internalized work that one might more easily connect to the poetry and fiction that marked her earliest artistic ambitions.

The photographs often describe the kind of minutiae that most of us look past: dust long settled on a kitchen table in afternoon light, a disregarded rag doll abandoned under the bed, wrinkles and chipped nail polish on aging feet. These pictures stand as monuments to the solitude that had evaded her (or that she actively avoided) for most of her life.

For several years, this way of working allowed for a radically different approach to being an artist, one that was more self-reliant than the photographs of unwieldy, temperamental children. That is, until 2004, when my mother’s first grandchild, my daughter, was born.

A few years later, a second arrived, and now there are more grandchildren

than children. And because it is what she does, the pictures multiplied proportionally. These photographs are decidedly different, in the way that being a grandparent is different from being a parent. There is a level of remove that allows her to fully rejoice in crying babies and their stressed-out parents— a particular way of staring that comes with lack of responsibility for the immediate well-being of the subject.