The Never-ending Search by Elisa Wouk Almino

Martin Buday’s photographs keep us searching—each image is an incomplete story. White arrows painted on the barks of trees point toward an impenetrable fog. In another frame, we are pressed up against a shut door, presumably someone’s house, greeted only by a drawing of Jesus taped above the lock. Most photos have no people in them. Some are settings that we imagine were once lively, like picnic tables on manicured grass, arranged before brightly painted houses. Other times we are plunged into landscapes that have no beginning or end: a desert, a field of pink and yellow flowers, a placid lagoon.

Buday has compared his photos to Wim Wenders’ 1984 movie Paris, Texas—how they both use color to create a mood. I see this, too: the way saturated hues (lime greens, hot oranges, deep reds) make everything more beautiful and lonelier at once. But what immediately came to mind when Buday first mentioned Paris, Texas to me was the movie’s opening scene, in which Travis, the protagonist, wanders the desert, an empty expanse ahead of him. “You mind telling me where you’re headed to, Trev?” his brother eventually asks. “What’s out there?” Travis, like us here, is not searching for something specific, but is perhaps waiting for that something to reveal itself.

In Buday’s photographs, we travel from Pennsylvania to Georgia to Colorado. It often feels like we’re pausing on the side of the road, catching a moment that would have otherwise been dismissed: the orange doors of a motel blinding against the snow, the silhouette of a mermaid swimming over a baby blue wall. There might hardly be any people, but we sense them silently and tenderly speaking to one another other, whether through vibrant signs placed outside stores or objects on display in private windowsills, like a sculpture of a cat poking out its tongue. A pair of empty chairs on the sidewalk invites our company, as does the hotel painted like a multicolored candy cane. They are evidence of the caring and peculiar ways in which we build and decorate our environments—of how we’re all just trying to get across to one another.

There is something vulnerable about Buday’s subjects, as though we caught them off-guard, as though they didn’t intend to be seen so intently. I’m thinking of the crashed, upside-down pink car and the discarded mattress patterned with flowers; of the rusting green pole holding up the sign to a convenience store in Savannah. The more we reach toward these objects, the longer we look, something curious happens: the sensation flips and we feel as though they are reaching toward us.

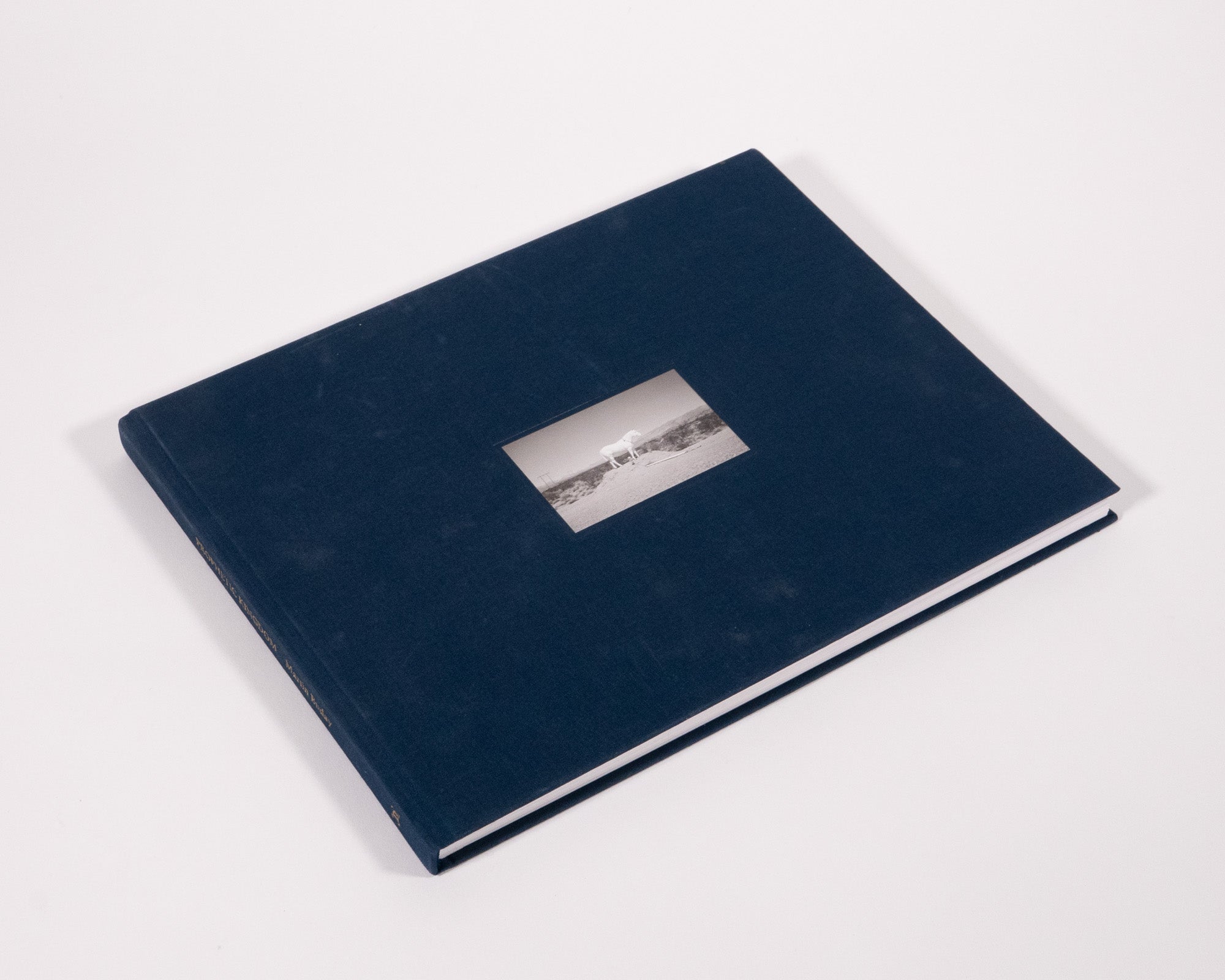

There is one collection of photos, though, that stands out: the ones featuring animals, both real and fabricated ones. There’s the monumental, concrete, wide-eyed elephant stalled in a misty, empty lot, and the caramel pony looking directly at us from behind a fence, on which a sign humorously warns, “Beware of the Dog.” There’s another sculpture of a serene unicorn that looks almost real in the black-and-white desert, and a great egret that meditates on a wooden ledge overlooking a canal. Our eyes fix on these animals. Confronted by their stoic and graceful sense of control, we feel to have found what we were looking for.

I am reminded of another movie, The Great Beauty (2013) by the Italian director Paolo Sorrentino. Similar to Paris, Texas, the aging protagonist, Jep Gambardella, aimlessly roams the streets of Rome to seek the meaning of his life. We only sense that his journey is coming to a conclusion when Jep faces, in the middle of the night, a giraffe in the ancient ruins of the Baths of Caracalla. Stunned, he takes off his hat and gazes up at the towering animal as it calmly wiggles its ears. Just a few scenes later, he is similarly amazed when dozens of flamingos materialize on his patio at dawn. In both instances, the animals disappear as suddenly as they appeared, causing a shift in our protagonist. He finds a sense of inner peace, perhaps; he is a little less restless, more aware of the remarkable beauty around him. In an interview about his film, Sorrentino described “this encounter with an animal” as “a sort of rendezvous with a truth to perhaps be found within yourself.”

What is it about animals? As John Berger writes in his 1977 essay “Looking at Animals,” they intrigue us for being like us, but not us. There will always be the silence held between our kind, an impenetrable mystery, which is maybe why for centuries we have resorted to animal metaphors and symbols to help explain our mystifying lives (the zodiac signs are just one of many examples Berger cites). The effect of stumbling upon Buday’s photos of animals is similar to Jep’s sudden encounters: they make us pause and look for that truth within ourselves— namely, that this constant, unknown search will never really end. It’s what it means to live.

Martin Buday

Martin Buday (b.1976, Doylestown, PA). Lives and works in Philadelphia, PA. Has a B.A. from the University of Pittsburgh and a M.F.A. from the Savannah College of Art and Design. He has shown in numerous group shows, has contributed to a wide variety of print and online publications and is held in numerous private collections throughout the United States. His first monograph will be published by Daylight Books in the fall 2021.