SURVIVAL IN A STATE OF FLUX

Jon Lee AndersonThe Cuban paradox is to present an outward appearance of timeless limbo while actually existing in a state of perpetual flux. Photographers are enthralled by the island’s uniquely distressed aesthetics, but invariably stymied by the fact that its wizened cigar rollers, ’50s Chevies and faded revolutionary signboards have become clichés. For them, the greatest challenge is how to get beyond Cuba’s stereotypes.

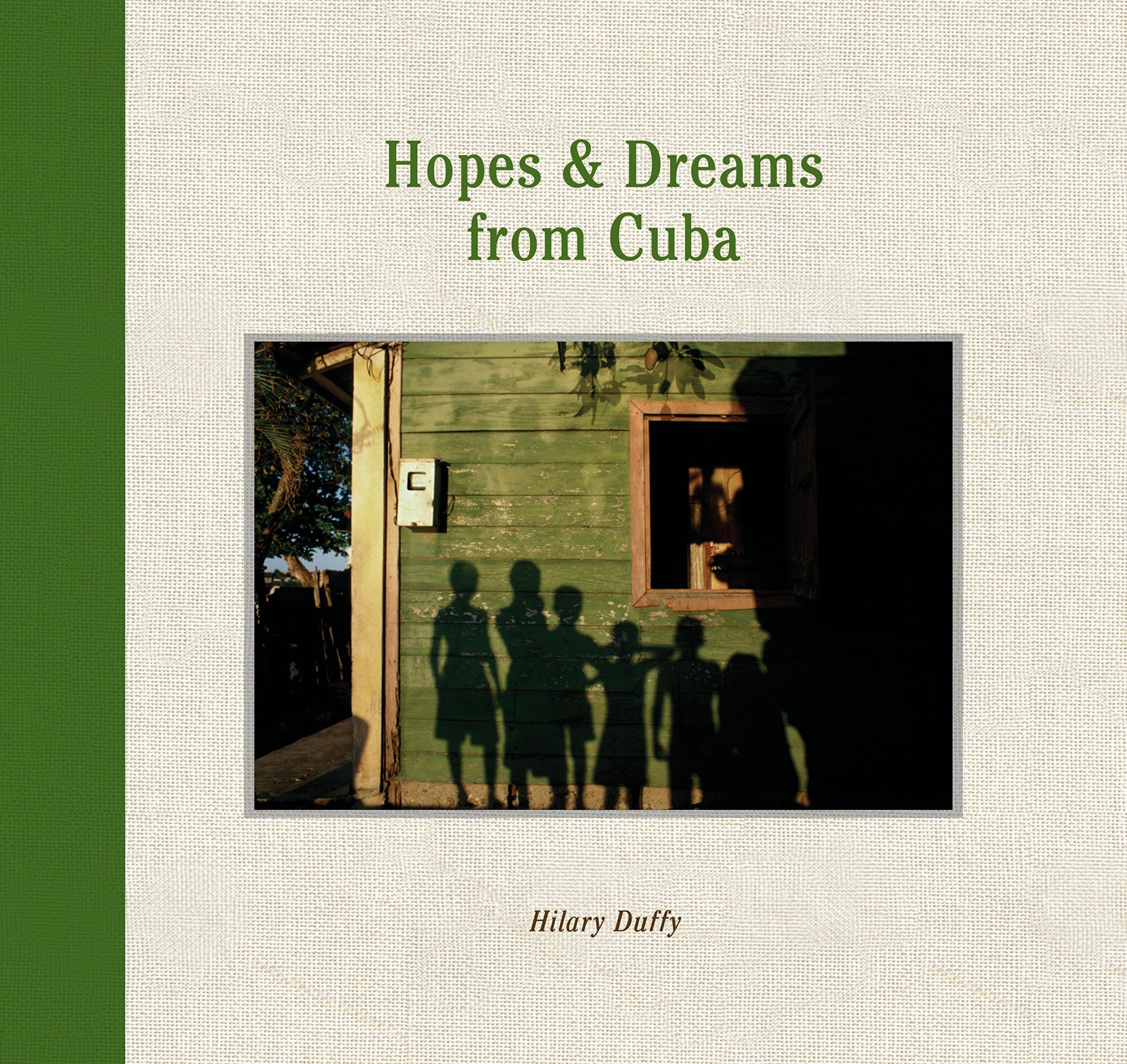

Hilary Duffy’s photographs are an insightful antidote to all that. These are images of people living out their lives in the most ordinary of ways: working, selling things, preparing to cook food—surviving. In others, they are at play, swimming in the sea, hanging out, getting ready for parties, laughing and talking, kissing one another. In many of Duffy’s portraits, people are looking at one another—openly, appraisingly, flirtingly—symbolic of the kind of human interaction that is vanishing from Duffy’s native New York, where mobile technology is replacing the habit of eye contact between strangers.

In one scene, a man prepares to dissect a pig he has slaughtered and laid out on a table on a city street—his cook pot ready on a wood fire and his neighbors observing from nearby perches—a reminder of how, in Cuba, the frontier between the public and private is often intangible. There is little that is overtly political in Hopes and Dreams from Cuba, little to remind us—as if reminding were necessary—that Cuba is a communist country. It is, one senses, an intentional omission. In a land where almost everything that is visible is the result of politics, why point out the obvious?

Duffy began traveling to Cuba and photographing there in the late 1990s, at the tail end of the so-called Special Period—Fidel Castro’s name for the belt-tightening era he imposed on Cubans in the wake of the Soviet Union’s precipitous collapse. With the end of three decades of generous subsidies from Moscow, life during Cuba’s Special Period meant putting up with widespread fuel shortages, daily electrical blackouts, and food shortages. In the countryside, oxen replaced tractors, and on Havana’s streets, Chinese bicycles replaced Russian cars.

Eventually, Fidel adopted a few emergency measures to rescue the country’s economy. They included allowing foreign firms to invest on the island with Cuban state partnership, and opening up the island to mass tourism. As an avowed Marxist-Leninist, however, he was unhappy about making such concessions, and insisted they were intended only as temporary measures to “safeguard the conquests of socialism”—by which he meant Cuba’s vaunted health and education systems, as well as its food-rationing and homebuilding programs that ensured that no one went hungry or became homeless.

Even so, the Special Period was a time of hardship and spurred social discontent. In 1994, rioting erupted in Havana and led to the Rafter Crisis, a three-week drama in which 50,000 Cubans who were fed up with their lives took to the seas on improvised seacraft to sail for the United States. Those who remained behind hunkered down and spent their days scrambling to find the means to get through from one day to the next, resolviendo, as they liked to say—resolving things. For some Cubans, resolviendo meant going hungry. For others it meant selling stolen cigars or rum from state-run factories or renting their bodies to foreign tourists in exchange for money, food, or bottles of shampoo.

With the beginning of subsidized oil shipments coming from Fidel Castro’s new friend and ally, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, in 1999, Cuba’s situation gradually improved. Buoyed by the turnaround, Fidel Castro’s revolutionary ambitions were reinvigorated, as well, and he launched what he called his Battle of Ideas, an attempt to instill a new generation of Cubans with revolutionary fervor. His plans were cut short in 2006 when he fell gravely ill, however. He survived, but his health remained fragile. Two years later, in the 49th year of his tenure in power, Fidel formally handed over his duties to his younger brother Raúl, who had served as Cuba’s defense minister since the early days of the revolution.

ESPERANZAS

HOPES

ALEJANDRINO

My dream was to have seen my eight daughters grow ,

study and work in this Revolution. Now that I am a

senior, I have retired from my state work.

Mi sueño era haber visto a mis ocho hijas crecer ,

estudiar y trabajar en esta Revolución. Ahora que soy

mayor, estoy pensionado de mi trabajo del estado.

FLOWAR

I dream of being a baseball star .

Quiero llegar a ser estrella de pelota.

JUANA

I have dreamt of so many things. I want to

build a decent house, but there is no budget.

I’ve only built five walls so far.

He soñado tantas cosas. Quisiera construir

una casa decente, pero no hay presupuesto,

solo he construido hasta ahora cinco paredes.

ARMANDO

My dream is difficult but not impossible.

The dream is to live in a world where

everyone is equal. I am sure I won’t see

this, but someday others will.

Es sueño mío es difícil, pero no

imposible. El sueño es vivir en un mundo

donde todos seamos iguales. Yo estoy

seguro que no lo voy a ver, pero algún día

será así y otros lo van a ver.

PEDRO

PEDRO

My dream? I keep that to myself.

¿Mi sueño? Eso me lo reser vo para mí.

Read the rest of Jon Lee Anderson’s Essay in Hilary Duffy’s new book Hopes and Dreams from Cuba.