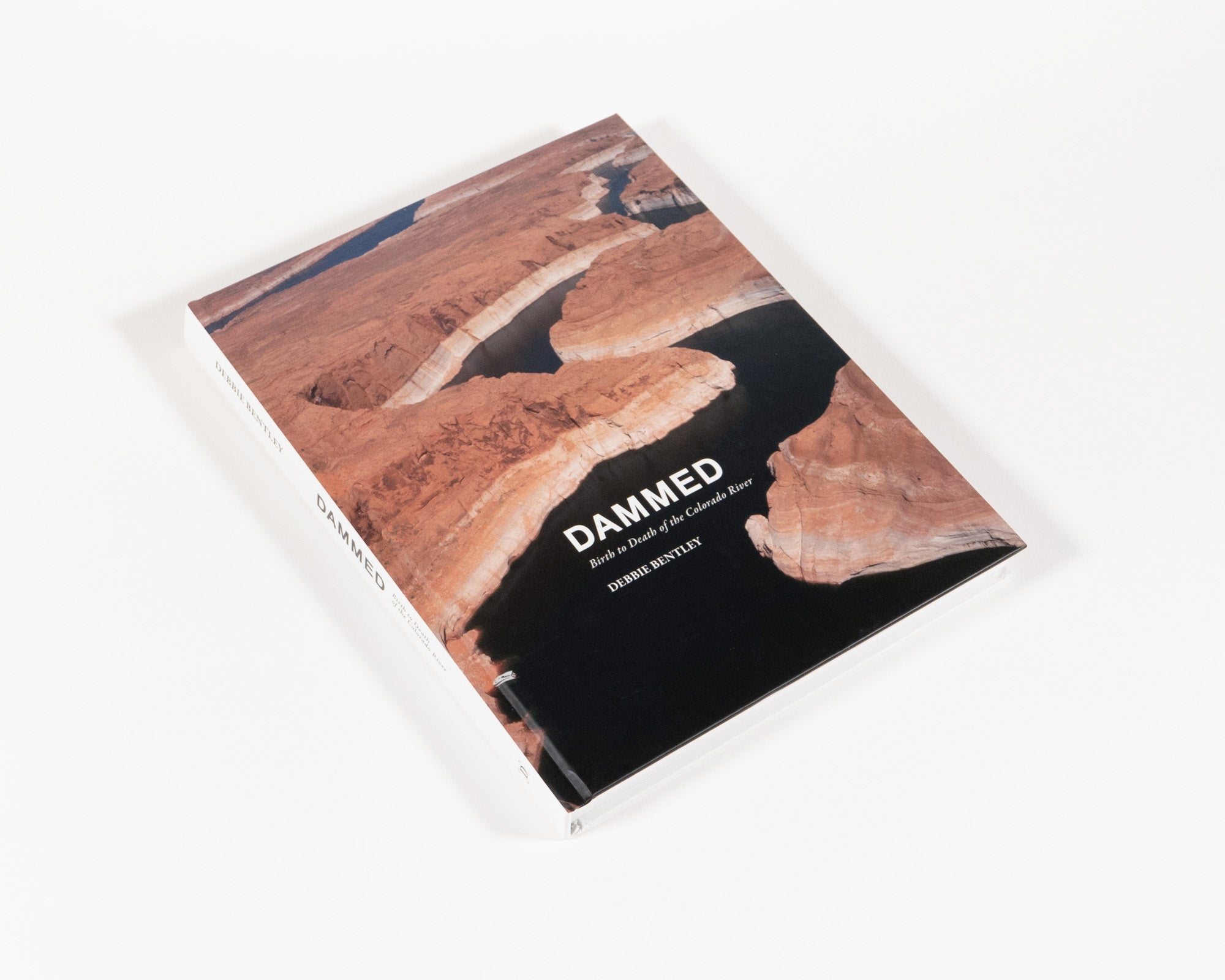

Dammed: Birth to Death of the Colorado River

When John Wesley Powell undertook his first Colorado River expedition in 1869, he encountered a river that today would be unrecognizable. Now dammed and diverted within a complex and interrelated system, the Colorado River provides water for 40 million people and irrigates 5.5 million agricultural acres in the Colorado River Basin and Mexico. Once flowing to the Gulf of Mexico and feeding a robust delta, the river’s flow now dries and disappears into the desert sands far short of the Gulf.

Many people do not consider where their water comes from as it flows from faucets, or think about the water used to grow the food on their table. Nor do they consider the electricity that flows to the light switch— electricity generated by the decreasing water levels at dams, such as Hoover and Glen Canyon on the Colorado River. They are removed from the origin of these waters, and their increasing scarcity. Unfortunately, data presented in the news and on television is often complex and difficult to visualize. This project sought to provide that visual connection so often lacking—a view of the entire interconnected and complex system to further understanding—coupled with background information to raise awareness.

To deliver such large amounts of water, the Colorado River has become one of the most controlled rivers in the world, with fifteen, soon to be sixteen, dams to impound and divert its waters on the main stem alone. Unbridled growth in the arid West and Southwest (Phoenix and its suburbs, for example, have ballooned from a population of 65,000 residents in 1940 to 4.6 million in 2021) coupled with legally mandated water deliveries required by the 1922 Colorado River Compact, have stretched the water supply to its limit. Added stress on the system comes from aridification, increasing dust within the basin, reservoir evaporation, and transit losses. Each one of these issues brings the river system closer to crisis.

To understand the system, it is helpful to start at the beginning. The basis for all current water delivery in the system are series of compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guide- lines collectively known as the “Law of the River.” The cornerstone of these agreements is the Colorado River Compact of 1922. This agreement was negotiated by the seven Colorado River basin states and the federal government. It laid out the relationships between the Upper Basin states and the Lower Basin states. Most of the water demands were in the Lower Basin, primarily as a result of growth and agriculture.

The Upper Basin states were concerned that the Lower Basin’s plans for Hoover Dam and other projects would deprive them of the river’s water in the future, under the Western water law doctrine of prior appropriation. The states could not agree on how the Colorado River’s waters should be allocated. Ultimately, Herbert Hoover, who was secretary of commerce at the time, suggested the basin be divided into upper and lower halves, with each basin having the right to develop and use 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) annually. In addition, the Lower Basin was granted the right to increase its use by 1 million maf per year. An acre-foot is roughly 360,000 gallons of water, or enough to cover an acre of land with water one foot in depth.

The Compact, however, was based on annual flows of 15 maf, even though data was available at the time indicating that long dry periods were common. Ranges during these historic low runoff periods were from 12 maf to 13 maf. Currently, flows range in the 12-maf area, with some years below that mark.

This 1922 apportionment did not end the disagreements over the control of the Colorado River. Modifications were made in 1928 with the Boulder Canyon Project Act, the Mexican Water Treaty of 1944, the Arizona v. California US Supreme Court decision of 1964, the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968, the Colorado River Water Delivery Agreement of 2003 (a.k.a. the Federal Quantification Settlement Agreement), and the Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead of 2007.

Notably missing from the Compact of 1922 were all rights due the thirty Indigenous tribes located in the basin. Numerous nations have begun to assert claims for water rights, which now amount to as much as 30% of the Colorado River’s waters. But most of this water is “paper water,” meaning rights are owned on paper, but there is no access to it. Often, rights haven’t been legally quantified and set, or the water is designated as single use and can’t be utilized for any other purpose. Often, there simply is no infrastructure in place to provide physical access to the water.

Currently, a new proposal generated by California, Arizona, and Nevada is under discussion but has not been ratified to date. California plans to contribute 1.6-maf savings over three years, with Nevada pledging to conserve 285,000 acre-feet, and Arizona 1.1 maf. In exchange, affected entities would receive $1.6 billion in federal grants. This proposal would end in 2026. By that time, theoretically, a completely new operating agreement will be in place, taking effect in 2026. The Bureau of Reclamation has said that the states need stop using 2 to 4 maf of water. This is about one third of the river’s flow.

Read the entirety of Debbie Bentley's Intro in her latest monograph, Dammed: Birth to Death of the Colorado River.

Debbie Bentley

Debbie Bentley is a photographer and multi-disciplinary artist from Denver, Colorado. Her work focuses primarily on the documentation of places and environments, their connection to the internal parts of people, and the need as an artist to see and record this connectivity.