Christopher Capozziello, a photojournalist currently based in Hamden, Connecticut, has worked on projects all over the United States, but for the past several years he has often stayed at home photographing his twin brother. Mr. Capozziello introduces his project, titled "The Distance Between Us," with the following statement:

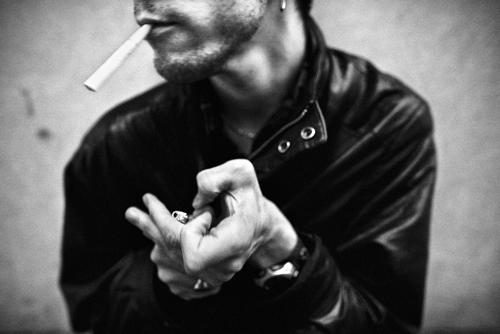

It’s two in the afternoon and he’s finally waking up. Last night, Nick was alone in the basement surfing the Internet, playing games, and going outside three or four times for a smoke in the backyard. He is meticulous about a great deal of things because he has all the time in the world. Today, he will probably absorb himself in organizing his CD’s, folding his laundry or counting and wrapping all of his change. He has been unable to hold down a job because of the muscle spasms from his cerebral palsy. Often times his body becomes contorted as the spasm takes place. His right foot will curl under him, his right arm will pull behind him, his left hand becomes difficult to move, he is unable to talk, and he often has to crawl up our hardwood stairs and into bed if no one is able to help him.

One of the hardest parts of being Nick’s twin is living my life, realizing that most of my experiences will always be out of his grasp.

In a recent interview with Daylight (below), Mr. Capozziello discusses this project, and others, as well as his intimate approach to photographic storytelling.

---

Interview by Trent Davis Bailey

Photographs by Christopher Capozziello/AEVUM

Daylight: What has your ongoing experience been documenting your twin brother? Has the act of photographing him changed or affected your relationship with one another?

Christopher Capozziello: When I first began making pictures of Nick, he didn’t like it. In fact, very early on, after I had just graduated from college and was living at home, I made a picture of him waking up. He immediately punched me in the face and said he didn’t want me making pictures of him. At that point I wasn’t making pictures with any real intention of telling his story, but what they became was a way for me to deal with our differences. In some strange way, as I’ve seen his story emerge, the pictures have brought us closer together. We spend more time together, talk on the phone more. That didn’t used to happen. The pictures have forced me to deal with the issues of guilt I’ve had about being the healthy [twin].

I have [photographed stories about] racism, drug abuse, cancer, and I ask questions of others, about how life is for them. In doing that it forces them to really dig deep and answer the tougher questions about life and why they do the things they do—or how their circumstances affect them. Somewhere along the way, I felt that I needed to do the same for myself and answer very personal questions. I think it’s only fair to do for myself what I ask of so many others in my other work.

From the project, "The Distance Between Us."

D: When you first made your photographs public, you posted “The Distance Between Us,” as story about a man named Nick suffering with cerebral palsy, omitting the fact that the subject of your story was, in fact, your twin brother. What made you decide to reveal this information?

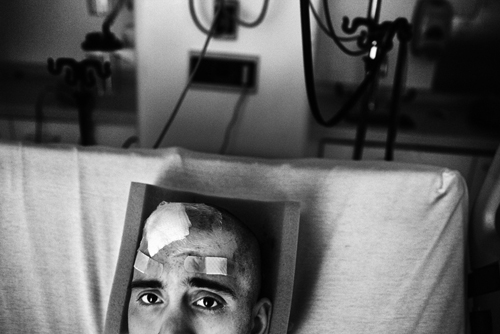

CC: A few years back, when I made my first run into New York to meet with [photo] editors, Nick’s story was part of a work-in-progress edit. Because I hadn’t approached telling his story in the sense that I had with other work, it was far from complete. At that point, to disclose that he was my brother would have raised so many questions about what was missing [from the story], but more than that, I thought it would sound trite to say, “This is my twin brother Nick. These pictures help me to deal with our differences.” I didn’t want people’s sympathy, and I didn’t want them feeling bad for him on the account that he’s my brother. If an editor or colleague asked questions about who he was I would come out with it, but five years ago I wasn’t ready to make that announcement on my own. Since the end of 2009, it has been such an emotional time for our family because of Nick’s brain surgery. [After the surgery,] it seemed like the right time to share his story and also to reveal that he was my twin brother.

I feel that, when there is suffering, it unites people in ways that other aspects of life do not. When I showed the work [at the LOOKBetween Festival] in Virginia, the response was more than I had expected. No one said, “Man, Chris, your pictures are amazing.” Everyone asked how Nick was doing, and then, almost always, people would tell me their stories, about their siblings, or a cousin, a friend, a parent, and how the suffering of these people affected them. Suffering unites. It brings about a solidarity that other aspects of life do not. [Sharing these photographs] has been extremely cathartic for me. This is the art of the ache.

From the project, "The Distance Between Us."

D: This addmittance of information certainly changes the viewer’s experience of your vision and subject. Has this changed the way you personally view and approach the project?

CC: I’m not so sure that the admittance has changed how I approach telling Nick’s story, or even our story. I have known for some time that if the story progressed to where there was real strength in the pictures, I would be very open about things, but me being open was contingent on that.

Part of the power of Nick’s story is how he has come to embrace what I’m doing. He used to hate when I made pictures of him, but I think he’s come to a place where he tolerates it. Even now, when I show him edits of the story, he says he doesn’t like it because he doesn’t like to see himself like that. That’s exactly my sentiment. But sometimes, he says, “You’re going to get me a girlfriend out of all of this aren’t you?”

I also am very careful not to make him feel like he’s some sort of project for me. I still treat this the same way I have always treated it. When I’m around it’s because I want to be around him or my family. When we go out and play pool and have a few beers, it’s because I want to be with him, not because I want to make pictures.

D: You also have created a multimedia piece for “The Distance Between Us,” which includes your narration and some words from your brother. Other than through your website, what are your intentions for how the work is to be viewed and displayed?

CC: Recently I have been applying for grants so I can spend more time on this and not have to be so absent from him because I’m trying to make a living and pay bills. If I had it my way, I’d be around much more than I’m able to right now. For me, this project is far from done, and it will probably be something that I photograph for the rest of our lives. In the meantime; however, I hope to have his story shown in larger editorial magazines and in exhibitions. An excerpt from his story was published in Virginia Quarterly Review this January, and it will be shown at the Center for Fine Art Photography in November. I’m also collaborating with MediaStorm on a larger multimedia piece, one that will tackle more of our story. The short multimedia piece on my site has always felt like a teaser with something more to come, so I’m excited about digging deeper with them.

D: You have a less journalistic, more literary approach to writing statements for your photography projects. I think your writing style is indicative of your photographic style in that both share a similar intimacy. What inspired you to introduce your features in this way?

CC: I remember as a child always trying to pull stories from my older family members. When I heard an interesting one, I would ask to hear it again and again. I think that when I’m telling someone’s story, I want it to feel honest. I like the text to feel conversational, like I’m sitting next to you recounting a story. Narration can be extremely powerful and revealing in this way, and often times, when we (photojournalists) write our captions in a matter-of-fact sort of AP style, we lose intimacy. There is certainly a place for more journalistic style caption writing, but when I'm telling a larger story, and have intimate access, for me it is more interesting and more revealing for the text to work in the same manner as the pictures: intimately.

Pictures need text for the viewer to truly understand what is happening in them, otherwise we can look at something and go on thinking the same way we did before. For example, how about the young woman I’ve been photographing who has a heroin addiction? She may have chosen this lifestyle, but I want to know why. For some of her friends, one drug has lead to another, and to another, finally bringing them to heroin’s door. As it turns out for Monica, from the ages of four to nine, she was repeatedly sexually abused. Now we want to listen. Now we want to look and get to the bottom of it all.

Text answers questions that pictures cannot. The two need each other, and when they’re married together in a compelling way, the truths about what a picture contains can cut deep. I hope with my work I’m able to do that. I’m as proud of the text I write as I am about the pictures.

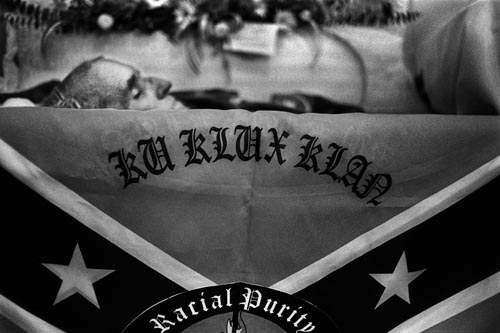

"I received the email yesterday, telling me that their imperial wizard died and that I could meet them at the wake. In the early evening, I nervously drive an hour to Petal, Mississippi, and, with the sun setting behind me, I make my first photograph of a klansman."

From the project, "For God, Race, and Country."

D: Your subtitles are also openly subjective, often describing how you came to make a specific picture. In your series “For God, Race, and Country,” for instance, you make it clear, as “a photographer from the North,” what your relationship is to your subjects. What do you feel is the value including this information rather than just describing what the image is depicting?

CC: Sometimes giving more context to the viewer answers some questions they may have about my relationship to the things I am photographing or about the specific moment I’m showing them. In the caption that you’re referring to, I made a portrait of Leonard, who in the middle of my interview, left me standing outside his trailer laughing as he ran inside saying, "You’ve never seen anything like this before." Minutes later he emerged with his robe and hood on. He did this because I was not from around there. I had no southern accent, and my license plate said Connecticut. So, he was trying to show me something I had never seen before, or maybe he was trying to scare me, to get a rise out of me. Whatever he was trying to do, he did it with laughter, and told me to make a picture. In this case, saying that I was a photographer from the North explains more of why he did what he was doing. It’s a very small anecdote that also tells us a little about him.

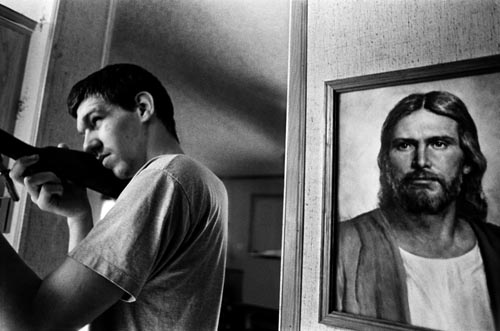

"David looks out the window down the barrel of a shotgun, and talks jokingly about how he'd like to go shoot up some blacks, reassuring me that he is only kidding; I believe him. And listening and photographing, and hoping this will say something, I can not help myself from looking at those open eyes that seem to look where David is looking."

From the project, "For God, Race, and Country."

D: It seems the Klan was very open to letting you photograph them. Was this the case and were their any limitations for you while photographing?

CC: There were always limitations. Some of them thought I was a sympathizer because I had the okay from their leader to make pictures. Then, when they would call me brother, or greet me with “White Power,” I would let them know that I was not a member. I didn’t do this in a judgmental way, but was gentle in how I handled these situations. Because of this, some didn’t want me photographing them or their family. Others were okay with it. There were times when I was threatened with guns and times when other members opened their homes to me.

There are no real limitations on how the pictures can be used, but once they’re published in a national publication, I will be done with that story because inevitably there will be someone who won’t like what I’ve shown or said, and things could, at that point, get dangerous.

---

For more information about Christopher and his work, visit: http://www.chriscappy.com