For photographer Michelle Frankfurter’s latest project she has been travelling to Mexico and embedding with Central American migrants who travel north by hitching the country’s railway system. The accumulative photo essay, titled Destino, treads the line between Frankfurter’s poetic personal vision and many of the didactic elements inherent to traditional photojournalism. The project is featured in the newly published BURN.02 and she is a 2011 photolucida Critical Mass finalist. In an interview with Daylight, Frankfurter speaks about working on her project and recalls the people she’s met, the books she’s read, and the many unforeseen experiences that have influenced her career.

---

Interview by Trent Davis Bailey

Photographs by Michelle Frankfurter

Daylight: Let’s discuss your project, Destino. Do you consider this work photojournalism or how do you regard it?

Michelle Frankfurter: The documentary scenes are not staged and the individuals portrayed are real, so in that sense I am working within the parameters of traditional documentary photography. I think of it as a work of historical fiction. The narrative is neither linear nor literal. It’s intended to be allegorical. I think of photojournalism as being utilitarian, representational, and illustrative: conditions exposed, situations documented. It isn’t my intent to record every aspect of the migrant journey through Mexico by train. (Something that has already been done extensively.) I rely a lot on mood to help carry the narrative along. I strip away identifiers that ground the images in any particular time period. Black and white film and the square format contribute a lot to the look and feel of the work.

Hermanos En El Camino migrant shelter, Ixtepec, Oaxaca, 2009

D: While many other photographers have already covered the migrants’ story, your photographs are different. There’s an optimism and stoicism to your subjects. Also, your images hardly reveal the inherent dangers along the railways, such as police, gangs, and immigration officials. Was this your intention to not include these sorts of scenes in your essay?

MF: I don’t think of it as covering a story—more like trying to craft a kind of visual epic poem within certain parameters. Some dictated by logistics, others by the practical limitations of the more cumbersome 6x6 format.

I don’t think it’s necessary to catalogue every aspect of the experience. I think there is much that is implied or suggested in the scenes I have photographed. Things that are subtle, layered, and nuanced in ways the work you mention isn’t. Take for example the photograph of the migrants and dogs under the makeshift chapel. There isn’t a lot of action in a dramatic sense, but the humble surroundings — the dogs on the ground with the sleeping migrants, the figure of Christ juxtaposed with the injured migrant — are the elements comprising the premise of the story.

Central American migrants ride atop a northbound freight train at dawn in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, 2010

D: You mention there were logistical limitations when following the migrants. What were some of the main problems you dealt with?

MF: On my first trip down, the main logistical problem I encountered was with the equipment I brought. Truthfully, I hadn’t planned on ever getting on the train. My initial thought was to make a series of portraits at the migrant shelters and along the tracks, so I brought my Ebony 4x5 field camera. Getting around in southern Mexico is actually quite easy. Mexico has an excellent mass transit system and you can get to any major city or town via bus. These are not rickety chicken buses either, but spacious, air-conditioned vehicles with reclining seats, overhead compartments and cargo space below. The towns along the migrant trail in Chiapas and Oaxaca are small enough to make getting around by foot or by taxi easy. But the equipment ended up being a giant pain.

First of all, it’s about 95 degrees down there in June, so ducking under a black cloth is like sticking your head in a furnace. It’s dusty and dirty. It was hard to find a clean surface on which to lay the gear. After I met the priest in Ixtepec and spent several days talking to migrants and hearing their personal stories, I couldn’t imagine not riding that train with them. Fortunately, I had thought to pack my Bronica 6x6 as a backup—in case the 4x5 ended up not working out. Unfortunately, I only had about 20 rolls of 120 film so I was going to have to shoot carefully. I’ve spent the past 24 years traveling to the region. In DC, I’m surrounded by Central American immigrants. My Spanish is fluent, which makes it easy for me to work without a fixer or translator.

Central American migrants ride atop a northbound freight train at dawn in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, 2010

D: What initially got you interested in the migrants’ story?

MF: I started a documentary wedding photography business in the mid ‘90’s as a way of generating a steady income and underwriting all of my personal documentary work. This was after coming back from working on a long-term project on Haiti that I paid for mostly with credit cards, which left me broke and in debt for a long time. I liked the idea of doing commissioned work for individuals … [and] this model worked nicely for a number of years. There was a kind of harmonious symbiosis as I went through each wedding season, taking off at some point every winter to pursue my personal documentary projects. Having scratched the itch, I would return energized and ready to tackle the next wedding season.

In 2009 when the economy tanked, I got sucker punched. My wedding bookings fell from a total of 24 per year down to eight. In 2009, I had zero bookings for June. I sort of fell apart. I had struggled the first six or seven years in DC, until I figured out a way to live and work as independently as possible. I used to joke that I had a trust fund lifestyle without the trust.

I had just read Sonya Nazario’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, Enrique’s Journey. It tells the story of undocumented Central American adolescents whose mothers had left them when they were very young to look for work in the United States. Predominantly from El Salvador and Honduras, these mostly teenage boys travel by rail across Mexico in search of their mothers in the United States. Along the way, they face a multitude of dangers. The book had a profound impact on me. It is a work of nonfiction, but the narrative is so compelling that in many ways, it reads like an epic adventure tale … [in which the migrants] have a singularity of purpose and determination, a kind of brazen resilience I admired. I grew up on the adventure tales of Jack London and Mark Twain, and then later on Cormac McCarthy’s border stories. To me, there is no storyline more romantic or compelling than one involving some kind of youthful odyssey across a hostile wilderness.

It’s somewhat ironic that photojournalism is never the medium by which I’m initially drawn to a project. I can be aware of a story but not see its potential because I don’t feel it. I finally stumbled onto the story after about nine years of circuitous wandering and thematic digressions because I suddenly felt its emotional impact. I finished reading Enrique’s Journey and I actually had myself a good cry over it. And then I felt really embarrassed that I had wasted a good couple of months moping about being a recession casualty. I had a fridge full of 4x5 Neopan and 120 Ilford film. I cancelled the pity party and booked a flight to Mexico City using frequent flier miles.

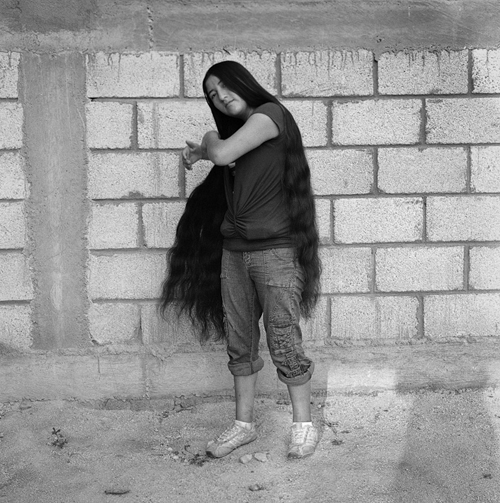

Salvadorian migrant, Hermanos En El Camino migrant shelter, Ixtepec, Oaxaca. 2009

D: Once you got to Mexico, how did you decide where to begin the project?

MF: On my first trip, I initially wanted to start in Tapachula, near the Guatemalan border, and work my way up north, back to Mexico City. I had heard about an amputee clinic in Tapachula that treated migrants injured in train-related accidents. It seemed like a logical starting point. I figured I would slowly make my way back north towards Mexico City. But a contact I had — a Facebook “friend” (a friend of a friend) — suggested, more like insisted, I go to Ixtepec, Oaxaca first. He had given me the name of the Catholic priest who ran the migrant shelter in Ixtepec, who was a big advocate on the migrants’ behalf. It ended up being excellent advice. I did eventually go to the clinic, toward the very end of the trip, but I wasn’t happy with any of the photographs I made there. It felt like I was covering well-worn territory and there wasn’t much new or different about the images I made. Had I started there, I may have lost momentum pretty quickly or hopefully, I would have had the good sense to move on.

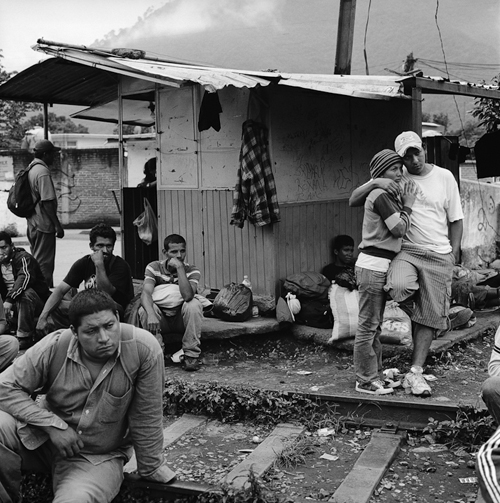

Home of Mercy migrant shelter, Arriaga, Chiapas, 2010

D: There are several quieter photographs in your project, like the bush growing in the courtyard, say, or the hanging bag filled with water. What do you feel these sorts of images add to your story?

MF: Much of the story is about the interminable waiting. The freight trains come and go according to no particular schedule. There are days of waiting within the confines of the migrant shelters. The shelters are safe havens but there is also a bunker-like feeling to them. The objects I’ve photographed are some of the things your eye settles on during the many hours and days of waiting. I think they add texture and have a quiet beauty of their own. Some of them, like the bush growing in the courtyard are intended to be symbolic and allude to the experience of the migrants.

Central American migrants wait for a northbound train by the tracks in the city of Orizaba in the Mexican state of Veracruz. There is no migrant shelter in Orizaba and migrants wait out in the open, often for days to catch moving freight trains, 2010

D: You’ve spent a lot of time earlier in your career covering issues in other countries in Central America, such as Haiti and Nicaragua. Can you provide a little background about how you got started in photography and how you eventually began working in these countries?

MF: My first ten years as a photographer were essentially spent in various awkward or painful stages of molting.

Growing up, my father always took a lot of pictures. He was a tenured professor in the School of Management at Syracuse University and belonged to Lightwork’s Community Darkrooms. At one point, he had set up a darkroom in the house. My dad was the consummate hobbyist. He baked bread, made furniture, and pickled anything that could be crammed into a jar. So I can’t really say that my interest in photography was directly related. In my family photography was considered a hobby, like quilting or raising pet ferrets, it wasn’t a career choice. I had always wanted to be a veterinarian, so I enrolled in the College of Arts and Sciences at Syracuse University and signed up for the core pre-med curriculum. But I was a total bungler in chemistry and math. By the end of my first semester, I pretty much knew that there would be disastrous consequences if I continued on that path.

Photography was an accident, an elective I stumbled onto while I was trying to figure out what to do. When I was out taking pictures, my mind got quiet. I was able to tune out the distracting noise and concentrate. Nothing had ever made me feel like that before. Up until then, I was a mediocre student. My GPA wasn’t high enough to transfer into the photojournalism school at Newhouse (School of Communications). But that didn’t stop me from taking the required photography classes in the PJ program. So I would say that, initially, my career as a photographer pretty much followed a predictable trajectory. I was the photo editor of the college paper, The Daily Orange, for a semester. I had a paid summer internship at the Syracuse Newspapers my senior year that got extended and became a part-time job. My first real job after college was at the Utica Newspapers. After nine months, there was an opening at the Syracuse Newspapers, and Tim Elliott, then Director of Photography, offered me a full time staff position, which I gladly accepted.

The Syracuse Post Standard and Herald Journal, the two dailies owned by the Newhouse family wasn’t exactly paradise for photographers. We all complained a lot, but thinking back on those days, it was a kind of golden era. For one thing, we were paid quite well, considering the cost of living in Syracuse, New York, and the job came with an extremely generous benefits package. And, if you had a good story idea and fought like hell for it, you were able to actually get some time to develop it, albeit around your three or four daily “bangers,” as we referred to assignments.

In 1986, I traveled to Haiti for the first time. It was a few months after Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was forced into exile, along with his wife, Michele Bennett, and things in Haiti were pretty tense. I remember the descent into Port Au Prince, the plane dipping over an immense mosaic of rusted tin roofs that made up the shantytown of Cité Soleil, wedged against the intense blue of the bay. Briefly, I imagined myself clawing frantically at the upholstery as flight attendants worked to pry me off the aircraft. There was a nightly curfew. After dark, the streets of Port Au Prince were deserted. It was pretty surreal. I was there for two weeks and barely slept the entire time, that’s how wired I felt. I was staying at a guesthouse in Port Au Prince … there was another photographer staying there as well. This beautiful girl with long, wavy dark strawberry blonde hair and every evening I would see her rushing, breathless up the guesthouse steps to phone her editor in New York. It was Alexandra Avakian and I think at that point, she had already been in Haiti for a couple of months. For the next two weeks, she let me tag along with her. I was like the kid in the back seat, lock-jawed with awe. When I left, I gave her the remaining black and white film I hadn’t shot and then climbed onto a plane and headed back to Syracuse, which was still in the sphincter-like grip of its early spring Soviet freeze. [Upon my return, I was] back to shooting pancake breakfasts and chicken fricassee dinners at the Baldwinsville Fire Department. The following year, I accompanied a local Witness For Peace delegation to Nicaragua. The paper published my photos in a two-page photo spread and a lead photo on the front page.

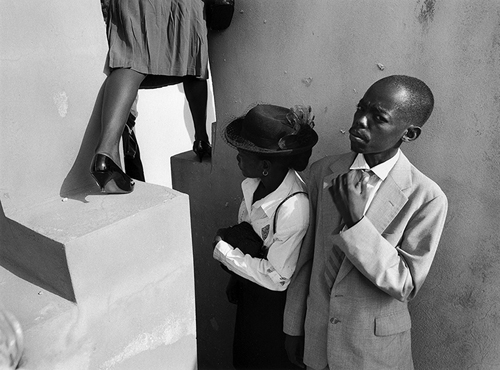

Funeral, National Cemetery, Port-Au-Prince, Haiti, 1994

Looters, Port-Au-Prince, Haiti, 1994

MF (Continued): Looking back on it, the job in Syracuse was the essence of the American Dream. You were practically guaranteed a comfortable job for life. One that came with annual raises, excellent benefits, and a yearly company clambake, but I was becoming increasingly bored and restless. A raging wanderlust, fueled by movies like Salvador, The Year of Living Dangerously, Under Fire, and The Killing Fields, and by my personal encounter with Alex Avakian, the poster face of exotic travel and cinematic life, was taking hold.

There was absolutely nothing in my upbringing that made letting go of all of that easy. Quitting my job in early 1988 was as counter-intuitive an impulse as stepping out a tenth-storey window. Secretly, I yearned for some kind of controlled Outward Bound adventure, one that would allow me to seamlessly step back into my life in Syracuse, full of worldly mystique and colorful anecdotes. In the three years that followed, I went to Guatemala to study Spanish for six weeks and then to Nicaragua where I worked with the human rights organization, Witness For Peace, for a year and a half. Following a brief and aimless period back in the United States, I bought a used Isuzu Trooper that I drove to Managua where I worked as a stringer for Reuters for about another year, which led to a disastrous love affair that quickly unraveled in Tel Aviv in the midst of the Gulf War. Not surprisingly, I wound up back in Syracuse with a broken heart and one barely functioning Nikon 8008 and a couple of lenses and hepatitis. But things had changed since I left. For one thing, my former boss, Tim Elliott had died of cancer a few months earlier, at the age of 36. His death was a huge and tragic loss. The country was in the midst of a recession. In short, the paper wouldn’t take me back.

I considered going to Sarajevo. I nearly went to Albania. I got on a train to New York, went to the Albanian consulate to get a visa, and then promptly took the train back to Syracuse where I languished on a friend's couch for the next six months, lamenting about “The Heartache,” until a good friend who I had met in Nicaragua finally convinced me to move DC.

It was rough at first. I had little work and a lot of time on my hands. I read a lot. I felt like I'd squandered my liberal arts education studying a trade. As a kind of redemptive exercise, I created reading lists. I read Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Dickens, Orwell, Nabakov, Gogol, Maugham, Hardy, Graham Greene, Melville, Poe, Faulkner, Steinbeck … I read You Can’t Go Home Again, by Thomas Wolfe. It echoed my current sentiment. Plowing through the classics taught me that universal truths are often conveyed as allegory, which is why they endure. It reshaped the way I thought about photography. Consequently, I became less interested in the literal news story, more interested in the figurative story.

With materials I scavenged out of alley dumpsters, I set up a darkroom in the bathroom of a crumbling, rat-infested building being rented as studio space. I charged a Bronica 645 and two lenses to my credit card and for the next two years, I photographed the people — mostly Black and Hispanic immigrants — of my Columbia Heights neighborhood. The Bronica taught me to be patient, to think, rather than react, to evaluate a scene and question its relevance. There are pictures that are “of” and there are pictures that are “about”. I was interested in the latter.

In 1994, with the help of a $3,000 project contribution from a friend and about one hundred rolls of TRI-X 120 film, I returned to Haiti. By then I was working as a freelancer, mostly for Newhouse News Services. Newhouse agreed to pay for my film processing in exchange for being able to use some of my images. Creatively though, I was on my own, and any editorial constraints were entirely self-imposed. I spent close to six months in Haiti. I was interested in the recurring themes that surfaced throughout Haiti’s turbulent history—things that were revealed as they bubbled to the surface during these cyclical spasms of political and social upheaval. It was the most exciting, liberating experience I had had thus far.

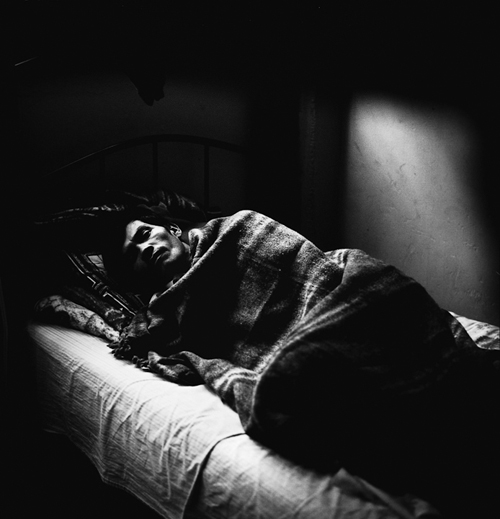

An injured Salvadorian migrant, San Juan de Dios migrant shelter in Lecheria, Mexico City, 2010

D: Do you plan on going back to continue your Mexico work or are you beginning any new projects in the near future?

MF: I’m still working on the migrant project. The model of financing this and future projects through wedding photography, unfortunately, is no longer viable. Realistically, I will need to seriously consider looking for support through grants, which are becoming increasingly competitive. I will most likely be turning to alternative means of support such as crowd sourcing—either that, or selling a kidney on eBay.

---

For more information about Michelle and her work, visit: http://www.michellefrankfurterphotos.com/