John Cyr is a Brooklyn-based photographer, and a Juror's pick in the 2011 http://www.daylightmagazine.org/content/daylight-photo-awards ">Daylight Photo Awards. Kate Levy visited Cyr in his studio, where they discussed the evolution of his critically acclaimed Developer Trays project. Images from Cyr's series will also be on display at AIPAD this March 29-April 1st through Catherine Edelman Gallery. Don't miss these beautiful prints in person.

Kate Levy: How did you stumble upon the Developer Trays project?

John Cyr: I was doing a fair amount of printing for other people in the darkroom. During this time, I started making photograms, with the intent to make a unique print. I was spending a lot of time looking at my tray, because I was doing these big printing jobs on the side. I started thinking about the tray’s uniqueness. I thought, “maybe I can still speak about the singularity of the darkroom print as an object, through this tray, which is also a unique object.” So I photographed my own tray. In the first images, I had cropped out the tray; the composition was very abstract. Then, I pulled back, and it became more about my tray, as opposed to just a tray.

My tray was somewhat interesting, but I knew that if I started digging, and if people would allow me into their darkrooms, I’d find some trays that were just crazy. Emmit Gowan was one of the first ones. That was the first tray I traveled to go shoot. His tray was awesome. It had these purples and magentas. His handwriting on the side read, “Dektol.” It was from the mid-60s. but was still in use at the time. That’s the other aspect of this project; photography is always flux and technology is always changing. It’s a bit like shooting with a Leica from the 1920s--you can still get great stuff, it doesn’t become obsolete. The tray, you can use it until it breaks.

KL: Theres a history containing all these images. Each image is somehow connected to one another, contained by the same developer tray.

As much as I respect and utilize analogue methods in my own practice, I’m also an advocate of digital in its accessibility. It dismantles the mythic being of the photographer as the only eligible recorder of history.

Do you think that your work ever hangs on to the history of analogue, and by extension tries to hang onto an elevated status of the photographer, which I think, maybe needs to disappear?

JC: This a pretty nostalgic project. But the way that I present it is very sterile; its the objects themselves that are nostalgic. I’m not trying to heighten this nostalgia through the way that I am photographing. I’m taking a literal representation of these objects that I was drawn to due to photography’s transition point right now. And, a lot of trays I’ve tried to get have all ready been thrown out. About 40% of trays I’ve photographed are not in use anymore. The photographers aren’t printing in the darkroom, but they haven’t cleaned out their stuff.

Its an interesting time, when I can still be around these artifacts, people still know what silver gelatin printing is. It doesn’t exist as an alternative process yet, although its close.

I’m also shooting them with a 4 x 5 and scanning them in. I’m combining both tools. I print them inkjet. The first time I did it, I thought that I was going to be a purist, but it was so boring. Without color, there’s too little differentiation between them.

I wanted to incorporate digital media. My aim is to reference the past, but still act according to the present. Everything available in Photoshop to me enables me to make the files as consistent as possible.

KL: Do you pretty much stick to the basic functions of Photoshop?

JC: I shoot with the 4 x5, and I position the tray on a black canvas. In Photoshop, I expand the canvas, and make the background pure black. I try to even out the light source if it’s not perfectly even.

KL: It seems like the joy of all of this would be working in Photoshop.

JC: I do enjoy working on these files, right after I scan them. The physical shooting part is always the same. But the experience to traveling to the place where these objects are in use is really special. Although a few people have mailed them, most of the time I am in their space. I went to photograph Ralph Gibson’s tray. He’s like, “I have a special treat for you.” Andreas [Feiningar] had given him his tray in the mid 1990s.

Andreas Feiningar's Developer Tray. Copyright John Cyr

KL: Thats incredible that you got to see how these heros of photography associated with one another.

JC: Ralph Gibson had the same enlarger that Robert Frank used to print The Americans. Larry Clark used it after that.

Its so hard to get to know people and get your work out there, I have been really fortunate to meet the people I have through shooting tray project. Its hard to get to know people and get your work out there.

KL: Neil Selkirk’s tray seems so energetically telling. I’m really interested in the disappearance aspect of this work--the disappearance of the developer’s power as you continue to use it, and of the surface of the tray as it is scratched away.

After Diane Arbus passed away, Selkirk was responsible for making all of her prints. He was given the job, as they were close friends. He didn’t have enough trays. He knew someone at Richard Avedon’s studio, so he called him up to ask if he could have a few extra trays. Thus, the Selkirk tray was originally Avedon’s. Selkirk made all of his own prints, as well as prints of Diane Arbus’s archive. He stopped using it about five years ago, because all these little marks were damaging the prints. In a darkroom, if you want to raise your washing tray, you can put a tray upside down under neath. That’s how it got all nice and moldy.

Neil Selkirk's Developer Tray. Copyright John Cyr.

KL: The subtleties of some of them really does draw a striking resemblance to the photographer’s body of work.

Have you ever thought about photographing other forms of equipment. or even the experience of going to the studio?

JC: My one regret is that I didn’t bring an audio recorder. I had great experiences with the photographers, but I missed a lot too. I don’t know how comfortable they would have been. I was trying to be as minimally invasive as possible, but also pick an object that shows a history more than anything else, in a way that is beyond how a photographer interacts with one of their tools. This is beyond the way a single photographer has interacted with their work. I focused on this, but didn’t really want to get distracted by anything else, shooting other people.

The connection I made with the person providing the tray felt as though I wasn’t trying to get something from them. I was photographing one of their objects. It wasn’t the same as taking a portrait of them.

KL: You are sharing the experience of the object, as opposed to putting them in front of the camera, requiring them to be or not be a certain way. I would imagine that the interaction was differed depending on whether it was with the photographer whose tray you were photographing, or with the anscestors of the photographer.

JC: Yes, these are completely different experiences. Also, I got to go into some archives, like at the Eastman House or the Smithsonian.

KL: What is one of the more interesting, challenging or ironic experiences you encountered while visiting one of the studios?

JC: Going to a someone’s home, and seeing how they live, and how their darkroom is set up is always intruiging and different each time. As often as I could, I would take the tray outside to photograph in the surroundings. I photographed Emmet Gowin’s tray right outside of his house, in his driveway.

Visiting Sally Mann was really great. I wrote her an email. She got back to me three months later. I was down there a few days later. I got to go to her farm and see the estate. When I was photographing her tray outside. She has five or six dogs. They were hanging out right around me, walking over the tray, and I was like, “Please don’t knock down my camera.”

This other connection to the object and its surroundings when I’m photographing it in the space is important. It doesn’t always translate into the work, but its an important aspect of their process and my process.

KL: Do you write about that?

JC: That’s what is going to be in the forthcoming book. Stories surrounding the experiences of the space and of photographing the trays.

KL: Have you ever found reflections in the trays?

JC: Sometimes I’m in there, but I blur it just enough.

KL: If you aren’t controlling the light too much, there is some inherent interaction with the outside. So i think the element of the outside does come through. [Looking at Eddie Adams’s Tray] This one would be so boring to me without the particular lines of light that show up in some of them.

JC: I was searching for a consistency, but not a vacuum.

KL: I think its really brave to have these interactions with all these people, and then just be satisfied to have the developer tray photograph be the relic of all of that. They are reduced, essential. The trays exist in this perfect state of liminality between digital and analogue, their textures speak to that as well.

Can we talk about some other work that led up to this project?

Copyright John Cyr

Copyright John Cyr

JC: I made my “14th Street” series when I was first thinking about the materiality of darkroom prints, and how this moment in photography is a time to be working off of that. I was printing at this studio that was in the process of moving. I didn’t really know what I was doing as far as work. I had all this expired paper and film. I loaded up my camera one day, and photographed all the for-lease storefronts as an homage to things disappearing, but new things coming. I printed multiple images on sheets of expired paper. I wanted to create an obstacle for myself in the darkroom. Having to print multiple images on one sheet is so easy in digital. In the darkroom, you have to be meticulous. Its all one exposure, so you get some darker and some lighter. So i tried to photograph on an overcast day, so the light would be even. I was trying to print heavy and flat. They are meant to be exhibited in a line.

KL: These feel a bit like a continuation of Zoe Leonard’s Analogue

JC: Yes. I was also thinking of Ed Ruscha. Generally, when I shoot I am very meticulous about composition, making sure everything is lined up within my 4x5 frame. With this series, I was taking the 6x7, and just lifting and shooting, letting it be what it will be. That was really satisfying. Throughout this whole project, I just tried to limit myself, and set up rules. I was in graduate school at the time [Cyr was in his second year of Graduate School when he began the Developer Trays project], and in this setting, its so hard to decide what you will do, so I had a list of rules. I shot all of the 14th Street series on one morning.

This was a big breakthrough for me in thinking about photography, my own work, and my place in what i’m interested in. I was figuring out how I can do it in a way that is still personal, but speaks in a ways bigger than my experience of leaving this darkroom that I had been working in.

KL: They are really exciting. Its great to see a lax in form with black and white analogue work. Zoe’s pictures are so formal and precise. Taking that one step further, and involving the element of chance and the dismantling of the photograph needing to be so formal.

[John pulls out a print of a black square, with barely intelligible figures emerging and receding into the composition.]

JC: This was the beginning of all these experimentations with photograms I was talking about earlier [These experimentations occured just prior to the “14th Street” series. This is a landscape. If you look closely, you will see trees. These are from images I had made previously. I was going off of the three basic tropes of photography: landscape, still life and portrait. They have to be lit so precisely. I was trying to make images that can’t be reproduced.

KL: It is hard to get that degree of faintness of image within the black.

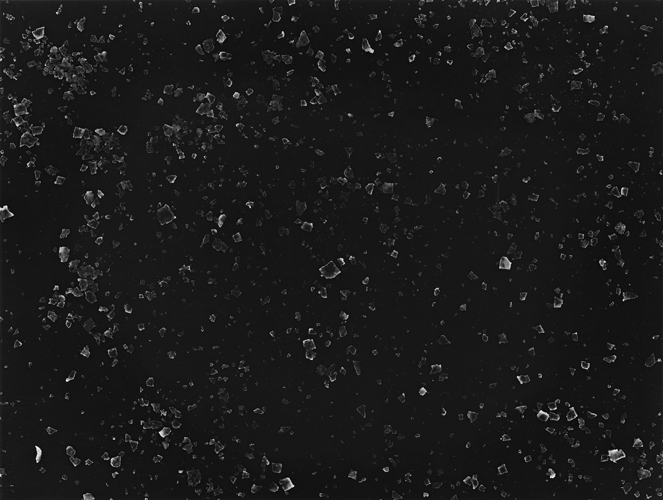

JC: I made some big prints of these too in the darkroom. I started with these, and then I started making these photograms of salt. All of this is on expired papers, papers from the 1960s.

Copyright John Cyr.

KL: I like the play of salt prints.

JC: Yes, they definitely reference the history of photography

KL: They remind me of Vija Clemins’s celestial landscape paintings. These could be the perfect opposite of this work. She literally spends hours and hours and hours perfecting this little tiny white dot that represents an entire solar system, but the painting is only 8 x 12.”

JC: Part of the fun with these was the celestial nature of them. I was really just trying to make something beautiful.

KL: It’s amazing that the salt showed up.

JC: I had to use really high contrast in the darkroom.

KL: It almost looks like a damaged print. It’s beautiful. I really respect your willingness to take steps and follow a process. You could have settled for the salt photograms, yet you've outdone yourself with the developer trays.

Linda Connor's Developer Trays. Copyright John Cyr.

To see more of Cyr's work, visit http://www.johncyrphotography.com/

To enter the Daylight Photo Awards, visit http://www.daylightmagazine.org/content/daylight-photo-awards ">http:// http://www.daylightmagazine.org/content/daylight-photo-awards