Lisa Mahar first started photographing her sons out of necessity. She took her first photograph in this series, a self portrait, when her sons reduced their bunk bed into a heap of splintered wood. It had been ten years since she had picked up her camera, but in that moment, she realized that photography might be the thing that would allow her to survive these trying events with her sons.

Over the past few months, I have corresponded with Mahar. I asked her to write a bit about her photographs for Daylight when I encountered her work at a Mary Ellen Mark workshop in which we were both participants. Although the workshop fell short in terms of intensive critique, Mary Ellen was really engaging in speaking about her own work. The same thing initially drew me to Mahar's photographs--the anecdotes that they both shared when discussing their images were so generative.

Although photographing one's own children is a far cry from dialoguing with individuals who form memory in vastly different cultural settings, Mahar's images often resemble documentary-style photographs of conflicts.

The following text consists of excerpts from our email correspondences.

Kate Levy: Why did you start photographing your sons?

Lisa Mahar: Initially I just wanted to document the challenging events so that I didn't have to internalize them. It was about self-protection, a way to diffuse the stress for me personally. The photographs could hold the tension so that I didn't have to.

Over time though, the images became more of a document of my children's emotional attempts at understanding themselves, me and each other. Ultimately, it allowed me to disconnect from the intensity of the experience so that I could reflect on our relationship rather than constantly react to it.

KL: How has this project informed your parenting?

LM: The process has helped me understand and appreciate that my children are struggling with the same issues I am - how to be part of a family and at the same time separate and independent. I think most parents and children are simultaneously pushing away from each other in order to define themselves as individuals, while pulling together so that they can feel valued and needed. It's a complex interaction that I think plays out in most intimate relationships.

Conflict emerges because we have to reign in our children's eccentricities and inappropriate behavior so that they can succeed in the world and at home. Yes, there can be unpleasant consequences from their acts of independence, but they're rarely disastrous.

My job as a parent is to prepare my children so they can eventually leave us. We connect so that we can eventually disconnect. It's a tenuous balancing act that interests me.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: Is photographing a way for you to take clues from them on what they need?

LM: Children need space to figure out what questions to ask and how to answer them on their own. Taking pictures helps me see that, because it forces me to become an observer.

I've learned that the camera has the ability to restructure an interaction. Occasionally, it brings me closer to my sons by helping us understand each other better, and sometimes it diffuses an emotional event, but it can also be a wall between us. At times it gets in the way of intimacy and dialog and can make everyone feel exposed and uncomfortable.

KL: Your sons inhabit a gaze of seductive challenge in many of the photographs. How were they acculturated to being photographed?

LM: I've photographed them since they were very young, so to a certain extent the camera is just an extension of my arm to them. But there are times when they really don't want me to take a picture, and can get quite upset about it. I haven't lost a camera yet, but there have been some close calls. At other times, they ask me to photograph them or something they've made. It's the same re-occuring theme--one day they push me away, the next they pull me in.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

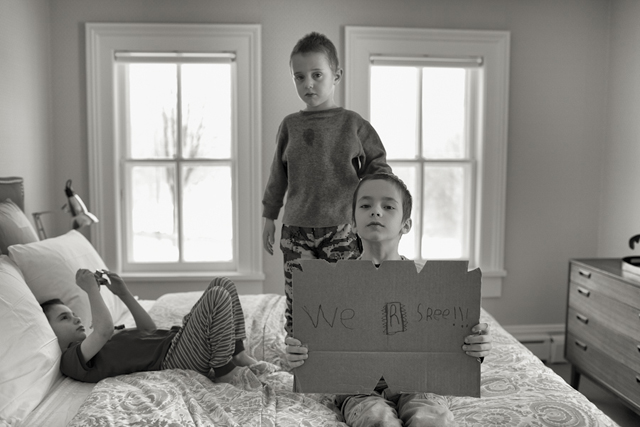

KL: In the "we r sree" photograph, what happened?

LM: You know, I don't remember. I have a pile of "I'm soree" letters and posters from a hundred different infractions. It could have been because they broke something they weren't supposed to touch, or they hurt each other, or tried to force one of the chickens to wear sunglasses.

We find ourselves saying we're sorry to each other often.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: There is one photograph where it appears as though one of your sons is going to be kicked in the back with a stick in his mouth. I am assuming that impending impalement was avoided. Can you recount some of the hairiest circumstances you have encountered with your sons?

LM: Moments like this--where all three children are interacting in dramatic ways happen often, but I'm not always fast enough to catch them. I wish my children were more skilled at using language to resolve conflict, but they often resort to using their bodies instead.

How a child displays emotion is different to how an adult will. It's immediate and transparent. You rarely have to wonder what a child is thinking or how they feel about a situation. It's instantly on their faces and in their gestures. They haven't had the life experiences that makes adults want to hide their feelings. This is admittedly what makes them great subjects. But these emotions are fleeting. What seems like the end of the world to them in one minute is a distant memory the next.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: Your oldest son, Emmett, seems to have quite the collection of cameras. Can you tell us about the roll photography plays in his life? What does he say about it?

LM: If you ask him directly why he collects cameras, he says its because they show what's real. Fiction and fantasy have no appeal to him. He doesn't think its possible for a camera to lie.

I think it's partly his way of connecting with me. Earlier this year he saved his money to buy the camera I had as a child--a Minolta SRT101, so he could recreate a double exposed self-portrait I took when I was 12, and then display them side by side in his room. I was very touched by that.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

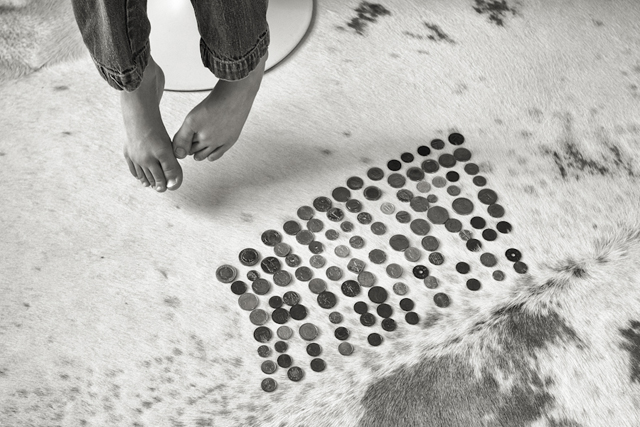

KL: You also spoke about Emmett's foraging at one point...

LM: All of my children are interested in foraging. It's an activity that makes them feel powerful. They enjoy having knowledge about a subject that most adults aren't familiar with, and they can pretend that they're more self-reliant than they actually are. Emmett also finds it amusing to shock people. Eating earthworms always does the trick.

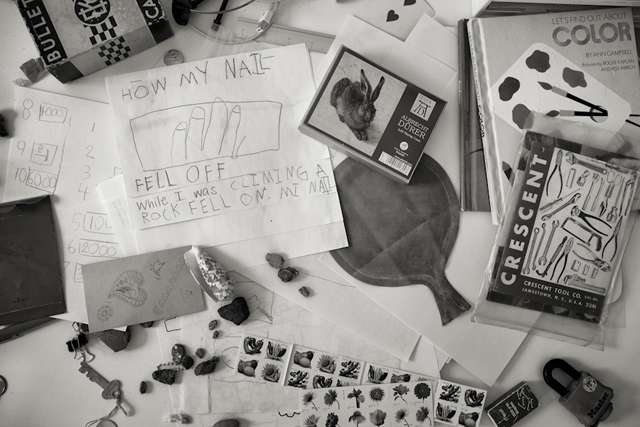

KL: What are some of your thoughts about how your children approach the process of making things?

LM: Children don't hold onto a fear of being judged that often paralyzes us as adults, and this frees them to produce highly original work. There's no lag between concept and execution. They don't think, "will people will think this is bizarre? Will they think I'm intelligent? Has this been done before? Should I think about this some more before I begin?" They just do it. The process tends to be much more important than the final product for them. The physical outcome is just a document of the journey, a relic of whatever idea they were trying to work through at the time.

My children inform my work in infinite ways. I'm inspired by their process and the questions they ask to guide it. They've helped me see that contradictions and imperfections aren't distractions or things to generate angst, but what makes life interesting and meaningful. They've liberated me from preconceptions and the constraints of perfectionism. It's allowed me to experience life in a far less judgmental way.

KL: Have you identified any questions that your children ask in their artistic processes?

LM: I'm impressed at how often chidrens' questions get right to the essential problems of existence. I admire the way they use whatever skill or tool is accessible to them to get at an answer: words, pens, paper, water, sticks, duct tape, whatever is around them.

One day when Emmett was five he asked me, "how do you make a bad person good?" I said I wasn't sure.

"You show them nice things like how to jump and flip," he said. "If you leave bad people bad, then they teach good people to be bad."

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: Are there also aspects of their personalities that affect the way you approach your work?

LM: My twins have helped me appreciate what it means to be truly collaborative with another person. They're entirely different people, but aware that they are part of a bigger whole. Until they were four, Eli would say his name was "Eli-Miles," and Miles would say he was "Miles-Eli."

Copyright Lisa Mahar

Spatially, they're constantly relating to each other, either in opposition or integrally connected. So much so that it's difficult to photograph them individually. It's helped me understand that no matter how separate I try to be, every interaction with another person is a collaboration to some extent.

Eli, in particular understands what makes himself and others feel the way they do, and it draws people to him. He has an intuitive sense of what motivates a person just by observing them.

KL: How can you emulate this with your camera?

LM: I've learned a lot from the painter Paul Klee, who was skilled at giving form to forces you can't see.

It's a fascinating challenge to think about how to make the invisible visible. I often wonder how I can reveal the things I perceive, but don't see.

KL: These photographs document a world cut out from any notions of the day to day reality, which seems a bit idealized. References to technology, contemporary modes of transportation, et cetera, are not present. Do you see including these things as a possibility for the work to progress?

LM: Emmett has an aversion to technology, so there's really nothing contemporary in the spaces he inhabits. And oddly, he's never found toys appealing. I don't have the same disdain, and neither do the twins or my husband, but we live in Manhattan, so our time at our farm is a break from that world.

I don't think the landscape is idealized, just rural. It's a place that gives me the opportunity to connect with ideas and at a pace that's better suited for self-reflection. I'm not nostalgic about the past--I welcome technology. But I do enjoy the way time slows here.

When Emmett was three and didn't want something to end, he would say that he wished the earth would stop spinning so that time would stand still and he could continue whatever it was that he was doing. It's a reminder that everything is connected and that each little thing we do affects the outcome of what comes next. On the one hand, nothing is that important, but on the other, everything is cosmically connected and therefore enormously significant.

Emmett still thinks about everything in relationship to time. He needs a historical framework to ground his ideas. When he was six he began to classify his things by date and period--books, bottles, even his family. He once described his father as a "mid-century modern" because he was born in the 1950s.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: How do you feel that your work differs from Sally Mann's infamous work with her own children?

LM: Other than the fact that we both have boys named Emmett, we photograph our own children, and shoot in black and white, I find the work to be very different. Mann's images are constructed; she has a clear idea about what she's going to end up with before she starts. Shooting with a large format camera necessitates that for her.

There's also an overt sexuality to her images, and a preoccupation about what it means to be a young girl, and how our culture perceives that vulnerable transition to womanhood. The tension in her work comes from one's assumptions about what is being shown vs. what's actually going on.

In my work, what you see is what you get. I shoot with a small format and capture moments as they happen. I don't set up shots, I just try to be at the right place at the right time. My children are constantly in motion--both physically and emotionally. Their reactions are raw and sincere.

Ultimately, I hope the work touches on some truths about the complexities and challenges of being responsible for another human being.

Copyright Lisa Mahar

KL: Do you think about how your children will look at these photographs when they are older?

LM: As a parent, I have a responsibility to think about that. Of course my children could say that the images are personal, and that they were not old enough to choose whether they wanted them taken or shown to others, and that would be accurate. But they couldn't say that the photographs were disrespectful or untrue. I hope they see that it was a way to help me better understand them and myself.

To have an honest record of one's childhood is something I've come to appreciate more as the years pass. When memories fade and the people that witnessed our youth disappear, the photographs take on a new significance. They remind you who you were and what you have become.

For me, it would be unsettling not to have a record of myself as a child. I think I'd feel almost as if I never existed. But I don't know if my children will feel the same. I'll have to wait and see.