Essay by Dr. Tony Macaulay

I was a paperboy up the Shankill, so I was. The dates of my employment were 1975–1977. As a twelve-year-old, I delivered forty-eight Belfast Telegraphs every night, around the streets of Ballygomartin at the top of the Shankill Road. At a tumultuous time in the history of Belfast, I had the great responsibility of delivering the daily news of bombs and bullets to my discerning customers.

Since then, I’ve lived in different places, worked in various jobs, and written many books. However, because of my memoir Paperboy: An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles (HarperCollins, 2011), I’m most well known for being a wee paperboy up the Shankill. It’s not unusual for strangers to come up to me in the street or in a café in Belfast and say, “What about ye, paperboy?”

Last year, I was standing at a bus stop in Douglas, on the Isle of Man, when a gentleman approached me and asked, “Are you the paperboy?” Once I recovered from the shock, he explained that he, too, had grown up in the Shankill community in the 1970s. When this happens, one of the reasons I’m delighted is because I love where I come from—the people and the place.

The Shankill community starts near Belfast city center and stretches up to the hills that overlook West Belfast. It’s one of the oldest roads in the city. The name Shankill derives from the Irish “seanchill,” meaning “old church,” referring to an ancient church site in the area dating back to the fifth century. The oldest maps of Belfast show the Shankill as a rural pathway with a church, connecting Belfast to the surrounding countryside. The Road (as locals call it!) became urbanized during the nineteenth century with Belfast’s industrial boom.

Over the next one hundred years, the Shankill developed as a working-class district with a population, like my family, mainly employed in the engineering, linen, and shipbuilding industries. Rows and rows of two-up-two-down red brick terraced houses were constructed to accommodate the growing workforce, and many Protestants and Unionists from rural areas of Ulster and Scotland, with a strong loyalty to Britain, migrated to this part of the growing city of Belfast.

In the late nineteenth century, my family, like many others, moved from County Antrim and settled in the Shankill. The terraced house where my great-grandparents lived still stands in Eccles Street.

During the twentieth century, the Shankill became iconic of the sectarian divisions in Belfast, separated from our neighbors on the Catholic and Nationalist Falls Road by a so-called “peace wall.” Some of my family lived in the streets that used to run between the Shankill and the Falls, where Catholics and Protestants once lived side by side.

At the outbreak of the Troubles in 1969, those streets became unsafe and were eventually demolished and replaced with barriers to keep our people apart. In the years that followed, the Shankill community suffered enormously from sectarian violence, paramilitarism, industrial decline, poor redevelopment, and persistent social, educational, and economic neglect. Despite all the hardships of history, the Shankill has endured with a distinctive sense of identity, culture, and community.

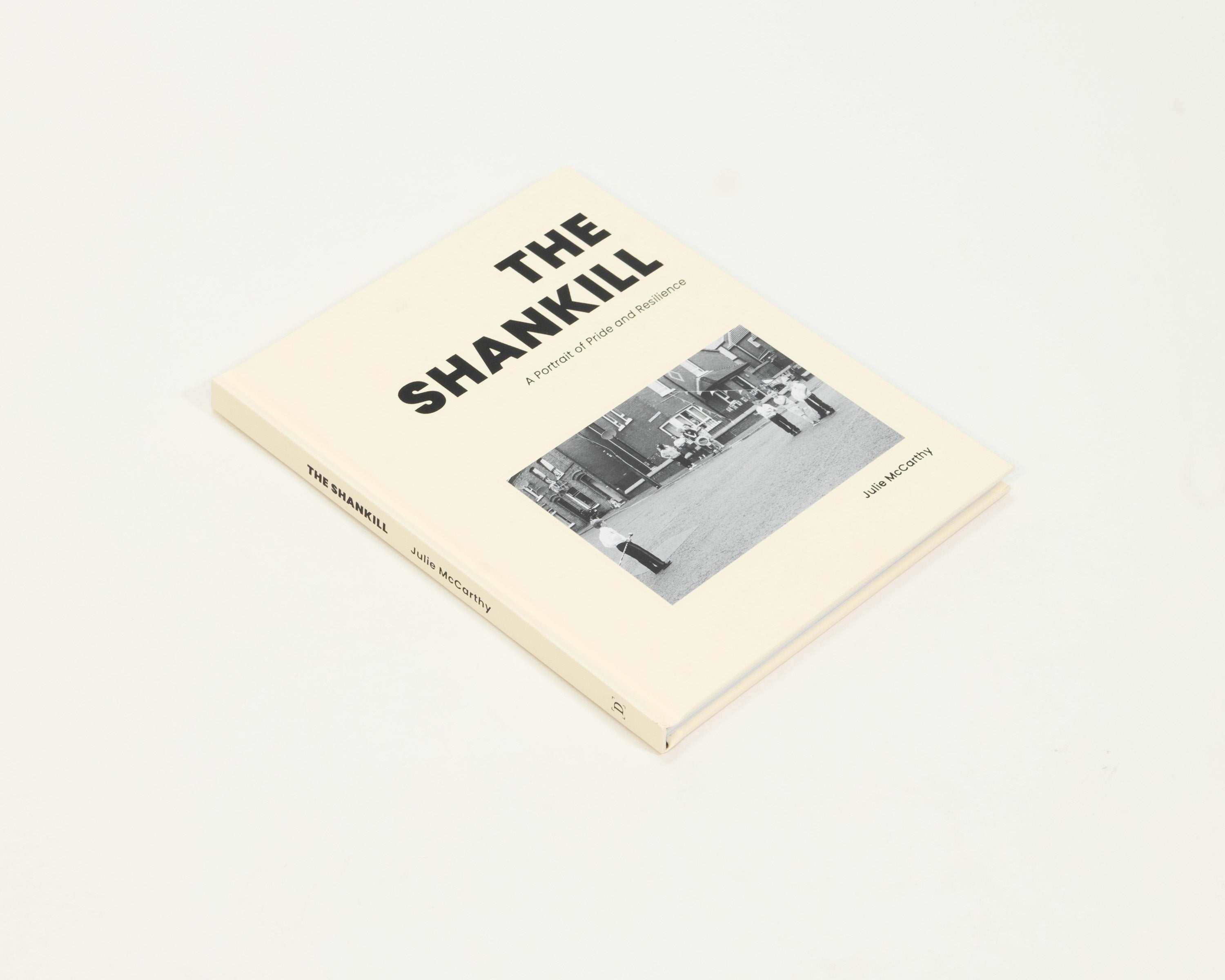

Read the entirety of Dr. Tony Macaulay's essay in JJulie McCarthy's The Shankill: A Portrait of Pride and Resiliance

Julie McCarthy

Julie McCarthy is a fine art photographer, having taken classes at Maine Media Workshops, International Center for Photography, NYNY and the Center for Photography at Woodstock, NY. Her work has been shown throughout New England and beyond.

Tony Macaulay

Tony Macaulay is a Northern Ireland author, leadership consultant, peace builder and broadcaster. Macauley grew up on the Shankill Road.