Walking In Olde Kensington

Olde Kensington, a small neighborhood just north of Center City Philadelphia, was predominantly a post-industrial area when I moved in, yet ominous signs of imminent change seemed to indicate that the fate of the place rested in other hands. Muddling my way through the unfamiliar streets on foot, the city seemed to push and pull me in this direction or that one, like it was leading me somewhere. Sometimes I resisted, others I followed, but I never caught a glimpse of my secret guide, who insisted on remaining shrouded in the empty spaces of the city. As a record of these ambulations, this work limns the tension between the extant and the imminent, the intervalic experience of living in a city in flux, and a complicated relationship to place.

In the mid-twentieth century, a small group of insufferably pretentious French intellectuals called the Lettrist International devoted themselves to the practice of the dérive; the act of perambulatory drifting through the streets of Paris. They were searchers, and what they were searching for was something they called the city’s psychogeography.

They looked for the “forgotten desires” of the city. They hoped to reorganize daily life by looking at aspects of the city that might be suppressed in the daily commute, itself organized by a series of destinations; school/work, home, and an arbitrary third-place. They hoped that by dismantling the geometry of this triangular order, people could live their lives more authentically. They wanted to better understand the systems of the urban environment, and subvert them. They sought to make the experience of life concrete.

They did this by walking around without a destination, listening to the language of the city, drinking and talking in bars, and embracing chance encounters with images of affirmation, negation, eccentricity, and revelation. Streets and alleyways speak quietly about which way we should or shouldn’t go. These places may appear on a map and yet, be empty in our minds. In other words, we know the place exists, but we haven’t been there. Cities are full of these empty spaces.

Photography re-organizes the visual world. The experience of living is made concrete through photography, but it is not accurate or true. The abstract reality it creates is a floating world. The space in-between photographs is blank. This gap in memory, this empty space, reverberates in the empty spaces of our own memories and ideas about our relationship to a place.

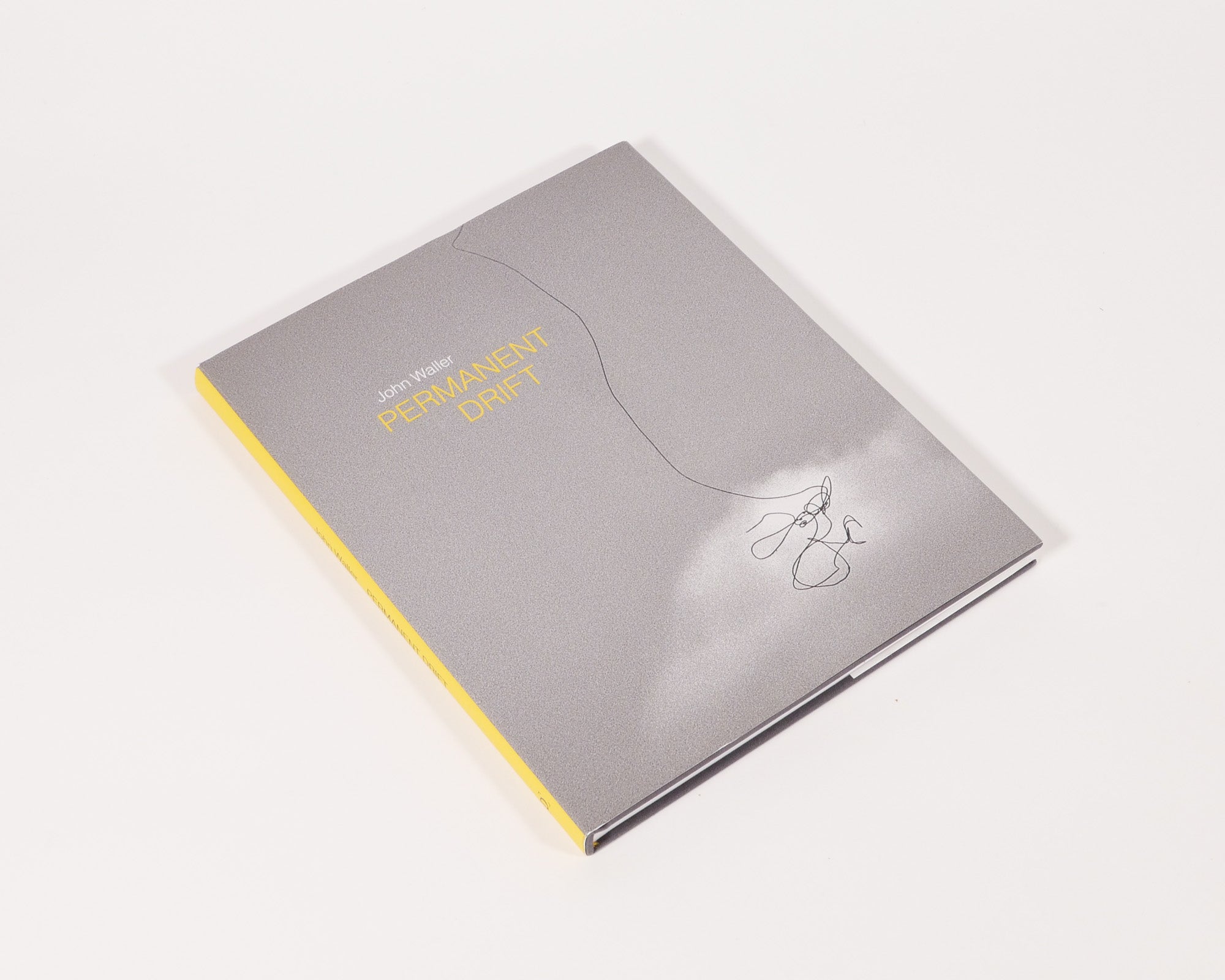

The story of Permanent Drift is simple; it’s about walking around a neighborhood in Philadelphia where I lived between 2012-16. The place was undergoing a major development push. I walked around the area repeatedly, without purpose, keeping my mind and eyes open. On a personal level, the work is about searching for home in a place that I found confusing and contradictory. When I was wandering around my adopted neighborhood, I was struck by a few features of the topography. First, a particular series of side streets which jutted across the city blocks in such a way that strongly differentiated them from the gridded blocks surrounding. Secondly, a large park with a swimming pool in one end that seemed to be perpetually damp.

Doing some casual internet research, I looked at maps and read a bit of the area’s history. It appeared that the swimming pool park was the approximate site of a lake or pond. That body of water fed into the Cohocksink Creek, itself running to the nearby Delaware River. It appeared that the creek echoed the approximate course of those jutting side streets. Further, I ascertained that the creek had been incorporated in the construction of the municipal sewer system. This subterranean creek became the central organizing aspect of the walks from then on.

At it’s core, the work is the result of a process of orientation. I was learning the lay of the land, and interrogating my relationship to it. What did it mean to live there? What was my identity as a Philadelphian? I’m not sure I’ve answered these questions. In fact, I continue to ask similar questions of my life in Massachusetts today.