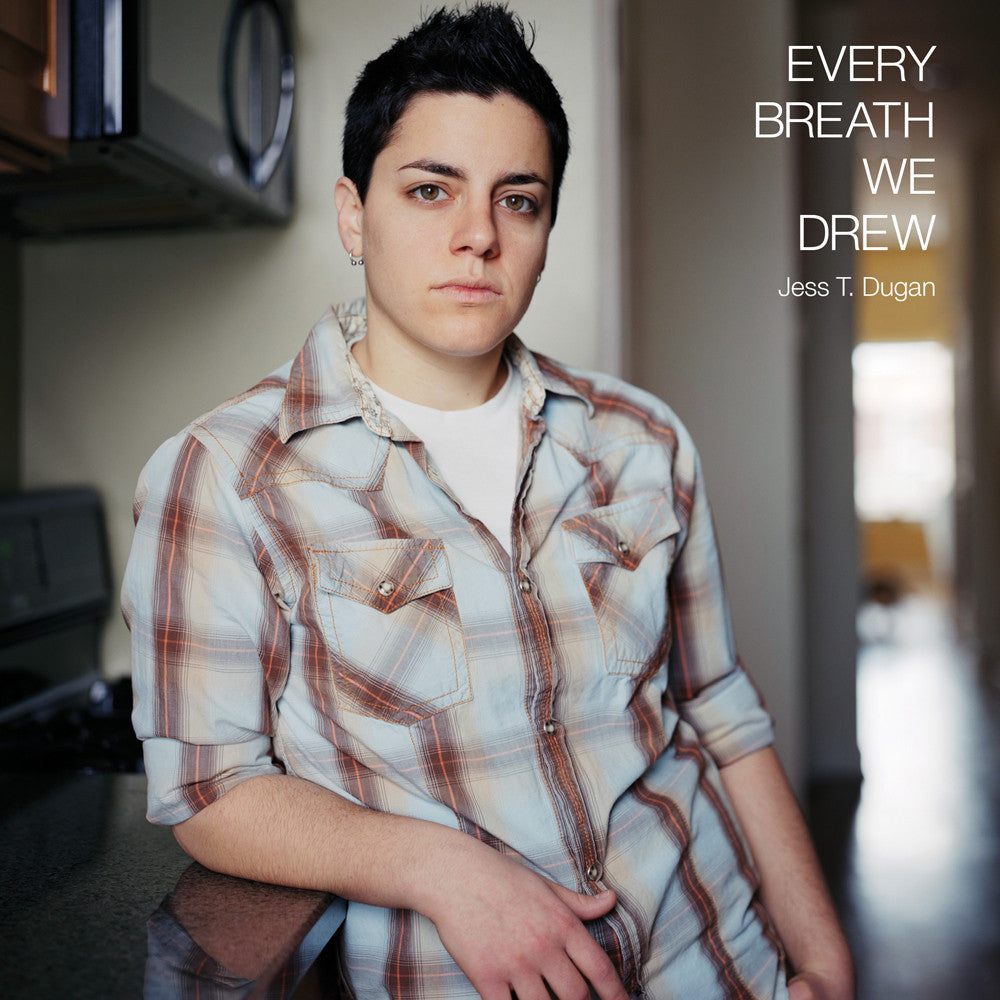

In Every Breath We Drew photographer Jess Dugan presents a collection of intimate and revealing self-portraits along with portraits of others. In them, Dugan explores the power of identity, desire, connection, and her own sexuality. Dugan explains, “By asking others to be vulnerable and intimate with me through the act of being photographed, I am laying claim to my own desires and defining what I find beautiful.” We found her photographs to be both gentle and revealing — enjoy!

Self-portrait (hotel), 2012

“The truth is such a slippery idea,” Jess Dugan tells me in a recent interview. “Photography traditionally has been so heavily associated with the idea of objectivity and documentation, but I think we all have acknowledged by now that there really is no such thing as truth in photography from a traditional, objective point of view.

In my current work, I am intentionally trying…to blur lines of gender and sexuality

“However, I do strongly believe that photography engages with truths, both universal and personal, in a very real way,” she continues. “In my current work, I am intentionally trying to work in the grey area, to blur lines of gender and sexuality and also of truth and fiction.”

Collaborating with subject and self, with intellect and emotion, with exterior and interior aspects of one’s body, and with photography’s strengths as well as its deficits requires a certain flexibility and creative humility that Dugan embodies. Her images are neither pretentious nor weak. They are direct, honest, and utterly present — qualities most of us strive to carry, the kind of presence in the world that implies an understanding that with every single breath we get closer to some kind of end, expanding the value of each inhalation, of each glance, moment, and individual.

Andy and Lee, 2013

Dugan’s images resonate like a flag plunged into the soil of each day

The process of inhabiting oneself as fully as possible and owning all aspects of DNA and familial history that contribute to our physicalness as well as our psyches, and at the same time exiling the cultural and social narratives we reject, is a lifetime project embarked on every waking minute of our lives. Dugan’s images resonate like a flag plunged into the soil of each day. “I’m here,” their subjects seem to say. “Do I like who I am and what I’m doing with my life? Now, what am I going to do about it?” The truths of roles — self, daughter, son, mother, father, friend, lover, and on and on — reconcile as identity, requiring honest self-engagement, as well as authentic engagement with those around us.

“By asking others to be vulnerable and intimate with me through the act of being photographed, I am laying claim to my own desires and defining what I find beautiful and powerful while asking larger questions about how identity is formed, desire is expressed, and intimate connection is sought,” Dugan says.

Ashley, 2012

By asking others to be vulnerable and intimate…I am laying claim to my own desires

A meaningful portrait, such as the ones Dugan makes, reflects the space that blooms between the subject and the photographer, the caught moment of interaction where some fragment of self is fused with another. Something hidden is revealed, even if in just a glance. What was intangible becomes available in the content of the image, a confession of visibility.