Girlhood: Lost and Found is an exploration of the experience young girls face growing up in a world full of preconceived notions of what it means to be a woman. Lost objects in the street coupled with intimate portraits mirror the many ways women lose their sense of identity as they maneuver through life as a female.

This work began as a personal journey to discover a way back to the person I was before I learned how the world saw me. But as time progressed, I realized that the larger mirror was my own daughter, and the bigger concern was how to raise her with awareness. I began traveling back in time, mining old journals and photo albums I had made throughout my own girlhood, as well as investigating archival magazine tears and photographs from my years spent in front of the camera working as a model and actor. I was in awe as synchronicities between the older materials and my adulthood, as well as the photographs I had already made of my daughter, began to reveal themselves.

The lines between lifetimes began to blur, and the mirror expanded further to include our shared past experiences and possible future fates. The collection of images as a whole examines multigenerational attachments formed in early childhood influenced by female stereotypes portrayed in our daily lives. In the spirit of deprogramming, parallel pasts are examined, proving history can repeat itself before we even have a chance to realize it’s happening.

I’m not exactly sure when the ritual of applying makeup to my face in preparation to enter the world carved out its place and settled in my subconscious mind. My earliest relevant memories, however, are of watching my mother get ready for work in the upstairs bathroom of my childhood home. It’s funny looking back, because my mom actually rarely wears and does not even like makeup yet she felt it necessary to draw in her eyebrows and paint her lids shimmering silver in order to go do her job.

I pause under the watchful eyes of my own daughter now, knowing that as much as I preach to her about her natural beauty, she is absorbing more than my words alone. “Why do you need mascara just to go to the grocery store?” she asked when she was about eight years old. She was right, I don’t, and in that moment, she herself was more of a mirror to me than the one I was staring in as I applied the black sticky stuff to my lashes as if it were war paint. As if my bare face alone won’t command enough power, or needs to be armed with a protective shield to hide behind. I can’t pinpoint the exact moment the brainwashing occurred. It’s an insidious process after all. When did it happen for my mother? Was it television? Magazines? The toys we were given?

The years I spent in front of the camera certainly didn’t help, but it was already in play long before then. All I do know is I did not come out of the womb thinking I needed to cover up dark circles or plump my lips. We are programmed as women at an early age to believe that our self-worth is tied to our physical appearance. As I raise a young girl while attempting to age naturally in a beauty-obsessed world, I long for the freedom that comes with unlearning. This unraveling of false teaching is my personal challenge, this work the vehicle by which I am traveling the course.

Those early years watching my mother’s face twist and contort into bizarre, painful expressions while applying her makeup in that upstairs bathroom felt like an out-of-body experience for me. I could see it was a struggle, a tedious chore, a nuisance. Yet, at the same time, I was mesmerized by the sparkle and color, filled with delight and inspiration at the thought of using the face as a creative canvas. I am still trying to find the balance between these opposing views to this day.

With each beautification act I participate in, I run the gamut of emotions as I observe myself from that same out-of-body place. I ask myself, What is really happening here? Am I a middle-aged woman fighting nature and denying my truth, or instead a woman in midlife owning her truth, confronting the aging process, and doing whatever the hell she wants with her physical appearance because she is in control and has the power to do so? Are these acts self-imposed forms of torture, or self-care? Am I truly having fun and expressing myself creatively, or caught up in a trap feeling forced to maintain appearances? At the end of the internal debate, it is my belief that all of these things can be true at the same time.

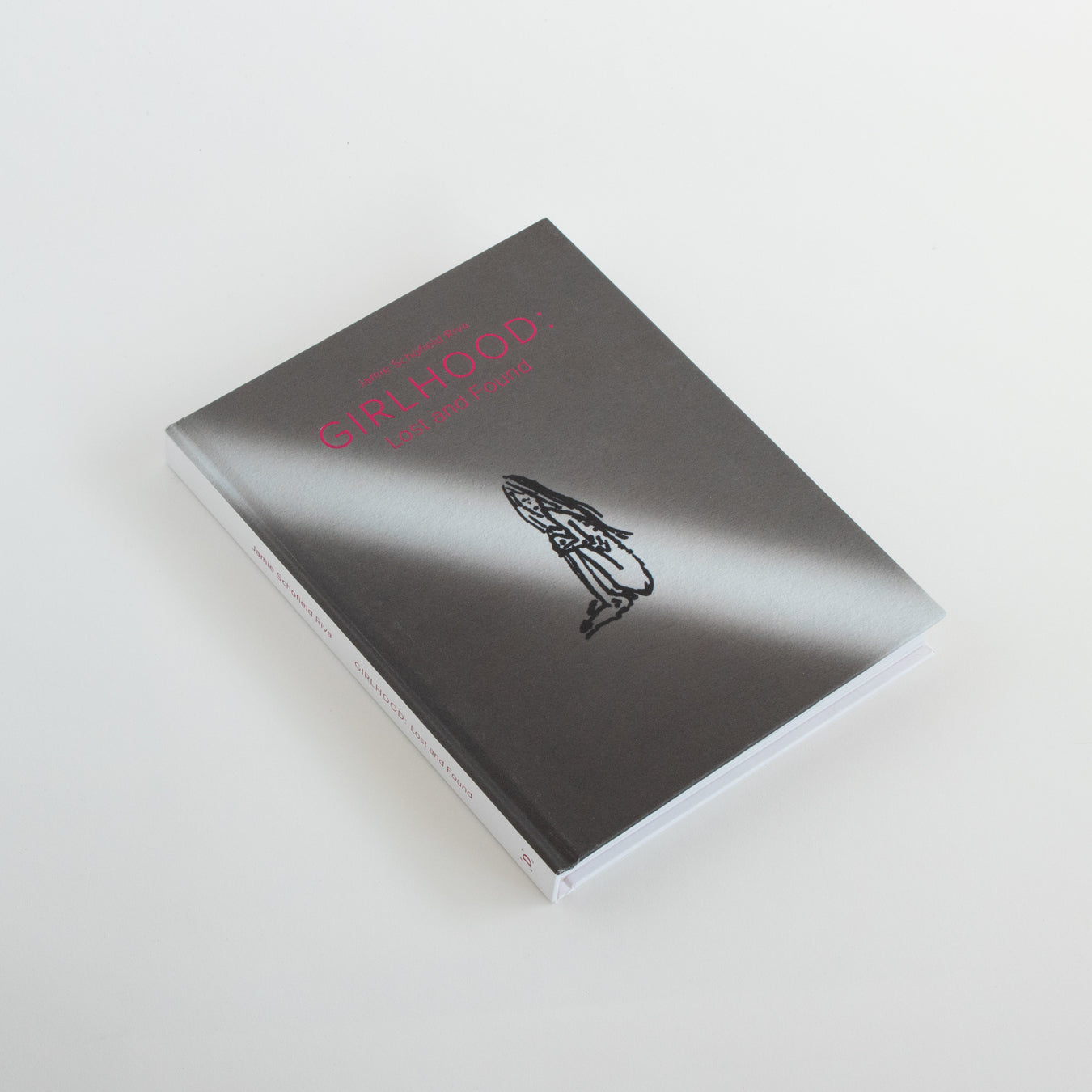

Read the entirety of Jamie Schofield Riva's introduction in her monograph, Girlhood: Lost and Found.

Jamie Schofield Riva

Jamie Schofield Riva is a documentary and fine art photographer based out of New York City.