SOL Y TIERRA

SUN AND EARTHMIGRANT ROOTS

SERGIO ANAYA

To the south of the Wall, life flourishes, defying the harshness of the natural elements and the weight of history. In the blazing sun of the desert, life counters with the fresh - ness of an adobe wall. In the long months of drought it emerges from the depths of a well or manifests in the murmur of a stream. Always free, always impetuous, life is expressed in the sharp thorns of the cactus as in the song of a woman kneading dough

Such is life south of the Wall, a motley jumble of sensations and challenges that strengthen the character of those who inhabit these lands and are accustomed to the daily struggle for sustenance of self, of their families, of communities.

These are the men and women, children or adults, Emily Matyas shows us in her photographic work. In their distant gaze, with a brow furrowed from time and sun, or in the open smile of people who befriend us spontaneously, the people seen here have been forged in a culture of struggle rich in memorable episodes throughout history, such as those years, in the middle of the last century, when the agrarian policy of President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940) gave thousands of families in southern Sonora ownership of fertile land that they organized into ejidos (communal lands).

For almost five decades the ejidatarios (communal landowners) and their families enjoyed a relative stability as owners of their plots, where they made a modest livelihood sufficient to feed everyone, with free health insurance, purchasing power for basic needs, and access to education up to the university level for young people who opted to emigrate to the city and study a profession.

Of course, it was not an idyllic world but a reality of flagrant contradictions, but circumstances were favorable to maintaining hope and an attachment to the land or city where one was born.

Thus it remained until the end of the 1980s, when the emergence of new economic models brought about their social and cultural impacts on the communities of southern Sonora, as well as the rest of the country and most of the world. The social sector of agriculture (the ejido) was supplanted by the voracious privatization that led the ejidatarios to sell their lands or lease them, and in a short time turned them into farmhands who for a miserable wage were now employed on land that once belonged to them and their families. Simultaneously, city workers were losing labor gains and seeing a decrease in the purchasing power of wages, in an economic environment designed for the benefit of large businesses and monopolies, to the detriment of small family businesses.

The most illustrative case is that of abarrotes (small neighborhood grocery stores), microenterprises that supported many families and that, for the past three decades, have been disappearing due to the power of business consortiums whose tentacles extend to neighborhoods and rural communities via the proliferation of “convenience stores.”

The growth of poverty favors the increase and empowerment of criminal groups that have emerged around drug trafficking. The climate is charged, not only because of the global warming that exacerbates droughts in southern Sonora, but also due to the lurking violence that impacts everyone, most lethally the poor.

Trapped in a spiral of poverty and violence, many inhabitants of rural areas and neighborhoods of southern Sonora cities see no other option than to migrate north of the Wall, where they hope to find the conditions for a dignified life, forged in a culture of effort and honest work, without letting go of the memories that nourish their hope. Memories materialized in photographs such as those in this collection, where two women look at the camera and we understand, as viewers, the nostalgia of those who observe them from somewhere in North America.

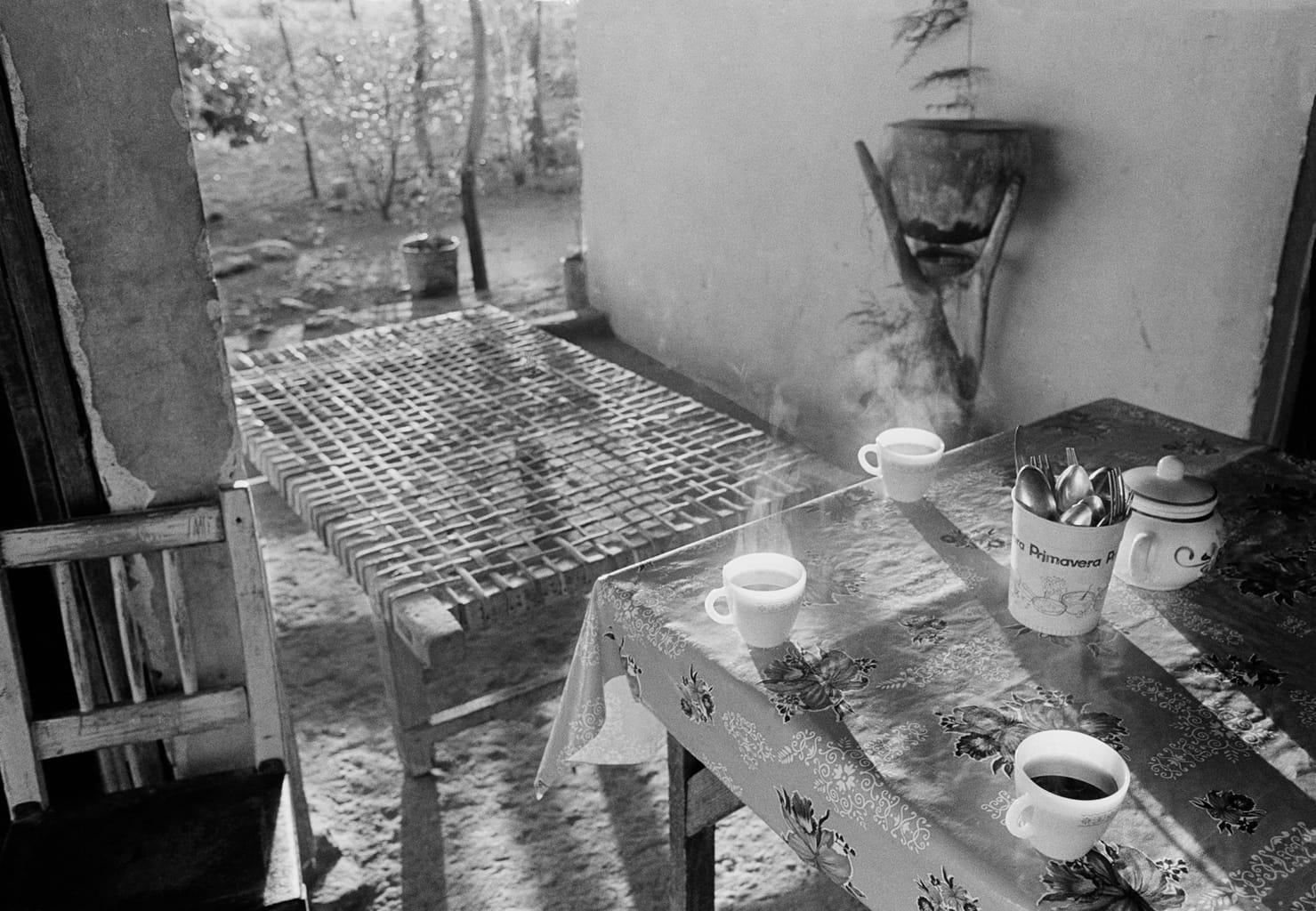

The graphic poetry of these images contributes to a better understanding of the world that migrants carry wherever they go. The laughter of children playing on a dirt floor in a patio, a mother, young and serious, showing off her daughter, the fire in the hornilla (wood-burning stove) that evokes the aromatic taste of freshly cooked tortillas, the religious devotion and Mexican baroque style still present in the humblest dwellings.