DAWOUD BEY: BEYOND THE MARGINS

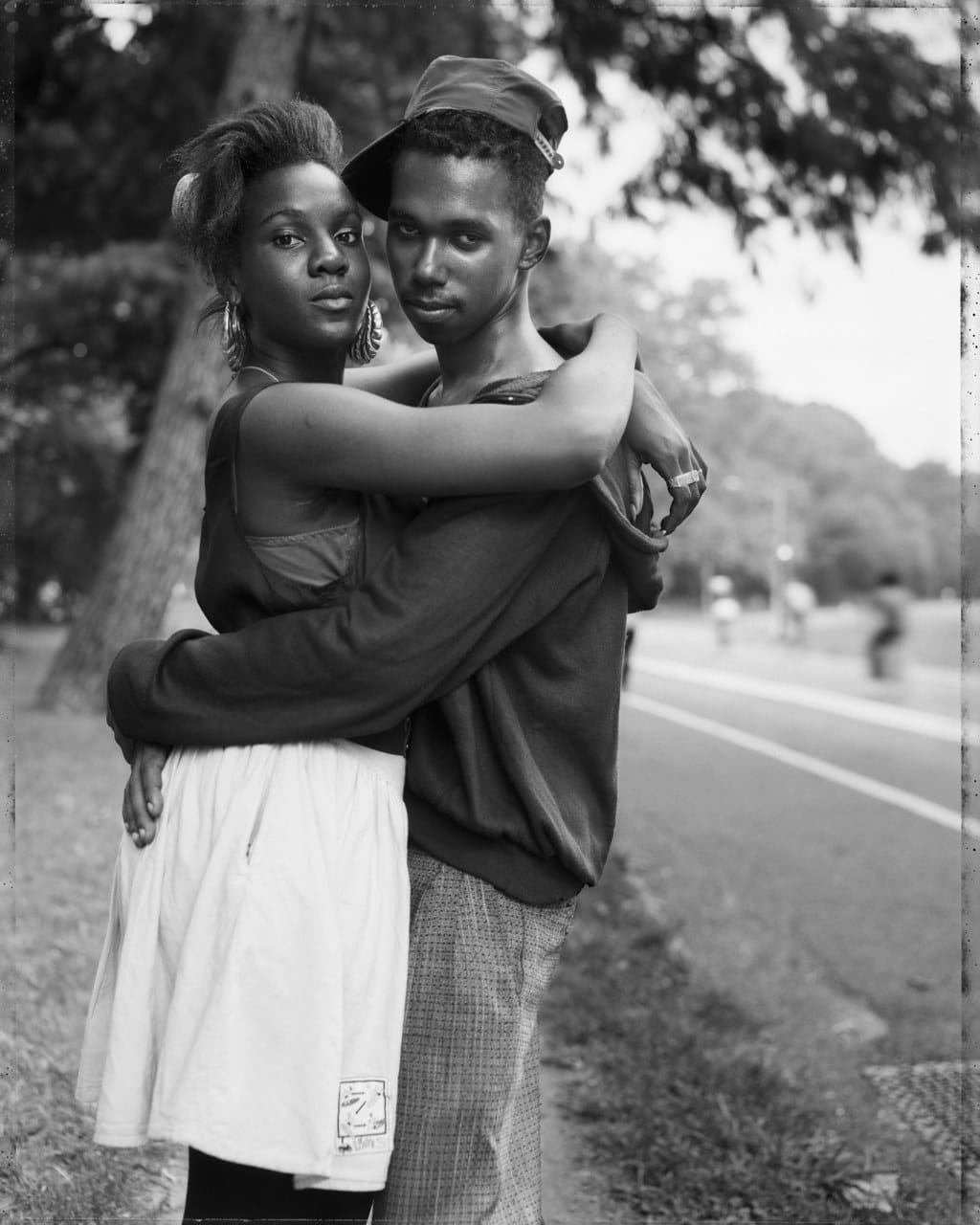

From “Street Portraits.” (1988-1991) © Dawoud Bey

Jon Feinstein:

When did you first realize you wanted to be a photographer?

Dawoud Bey Working In Celeveland, OH Photo © Mike Majewski/Front Triennial

I guess the moment when I decided I wanted to become a photographer was when I found out that there were indeed such a thing as black photographers. Though I knew of Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee before then, my first serious realization that there was a community of African Americans for whom photography was central to their lives was when I saw a copy of The Black Photographers Annual, which was first published in 1973. I had earlier become attuned to photography through going to the Harlem on My Mind, exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969 when I was sixteen years old. But the Annual gave me an even deeper sense of the range of work being done by black photographers. So that was an important and affirmative turning point for me.

The Black Photographers Annual, Published In 1973, Was The First Of Four Volumes, And Included Photographs By Beuford Smith, Lou Draper, Jimmie Mannas, Shawn Walker, And Others, Was A Major Influence On Bey’s Work And Practice.

Feinstein:

Did you have any photographic mentors in these early days?

Several of the photographers in New York who appeared in the Annual>/i>, and had in fact created it, became my earliest mentors and friends, including Beuford Smith, Lou Draper, Jimmie Mannas, Shawn Walker, and others. It was through them I began to understand what it was to live one’s life committed to the making of photographs that contributed something to both the larger culture of picture making, but that also represented something of what it specifically meant to black and working within that medium. Later on that community expanded when I met Jules Allen and Frank Stewart, who also published in The Black Photographers Annual.

Feinstein:

What was the first photograph you recall being “proud” of making beyond just a casual snapshot?

“A Man In A Bowler Hat,” 1976. © Dawoud Bey

The first photograph I made, in 1976, that met the level of expectation that I had set for myself, in terms of the kinds of photographs I hoped to make, was “A Man In A Bowler Hat.” It was a classic and almost timeless photograph of a man that looked like it could have been made forty years before. It was the first time I had to interrupt a social situation in order to make a photograph, where I realized that making the kinds of photographs I wanted to make required a set of social skills in addition to picture making skills.

Feinstein:

To my understanding, you’ve always worked with a large format view camera. Why is this important to your practice and how you “see”?

From “Street Portraits.” (1988-1991) © Dawoud Bey

I started making photographs seriously in 1975, and didn’t begin working with a 4X5 camera on a tripod until 1988. When I started, I was working with a 35mm camera…specifically a black Nikkormat, a fairly compact single lens reflex camera. I never liked the Leica rangefinder cameras that a lot of my photographer friends were working with. There was something about the ground glass that seemed intrinsic to me as the place where the experience of the world began to become translated into a photograph. The rangefinder, with its plain piece of glass, didn’t do that for me. So I’ve always responded to putting the camera up to my eye and looking at the world directly through the lens, which one doesn’t do with a rangefinder. And when I started, I was also was working with the small camera in a far more deliberate way than it was traditionally used. I made only one or two exposures, taking considerable time, which of course is more like the way one uses a view camera. In 1988, to change both the nature of the relationship that I was having with the people I was photographing, and to make a different kind of photograph materially, I started using a 4X5 camera for the first time. I wanted to make a photograph that contained even more material information than the small 35mm negative provided, and I also wanted to create a more clearly participatory and conspicuous process for making the work, a process that brought me and my subjects into a more heightened relationship for the time it took to make the photograph, I was using Polaroid Type 55 Positive/Negative film, which allowed me to give them a print as soon as the informal street portrait session was completed. This process of reciprocating be giving them their image was also intrinsic to the way I wanted to work at that time. The photographs that I then exhibited created a large scale presence within the space of the gallery or museum for these African American subjects. This of course was also informed by that initial experience of seeing photographs of African Americans on the wall of the Met in the Harlem On My Mind exhibition.

Feinstein:

"From your series Harlem USA to The Character Project, Class Pictures, Strangers\/Community, Birmingham, and Harlem Redux, what’s the most important link for you?"From your series Harlem USA to The Character Project, Class Pictures, Strangers/Community, Birmingham, and Harlem Redux, what’s the most important link for you?

I think for me the most important thing about the work I’ve made over the years is that it engages issues and subjects in the real social world in a way that foregrounds those things and heightens our engagement with them, whether that be a black urban community that has often been visualized through a framework of dysfunctional social pathology, young people who have been essentialized and stereotyped by the large society in some way, or a community currently undergoing a radical reshaping through the forces of gentrification, I want to make work that is about the things that are in the world that matter to me, as someone who tries to remain critically engaged, and through giving those things resonant form in my own work then make them matter to the people who view my work.

From “Harlem, U.S.A.” (1975-1979) © Dawoud Bey

From “Strangers/Community” (2011-2013) © Dawoud Bey

Three Portraits From “The Character Project,” 2007 © Dawoud Bey

From “Harlem Redux” (2014-2017) © Dawoud Bey

From “Harlem Redux” (2014-2017) © Dawoud Bey

Your recent series Harlem Redux, works in conversation with work you’d made decades earlier. Did making this work give you any new insights on the original series?

Harlem, NY is currently being reshaped in profound ways, largely through the forces of gentrification. This is creating an eroding of place memory and a diminishing of cultural memory as significant pieces of Harlem’s past disappear. I wanted to make work about what change looks like as it is taking place. My earlier Harlem photographs were motivated in part by my family’s history there. My mother and father lived in Harlem and met there in St. John’s Baptist Church. So Harlem is the beginning of my own personal narrative, a significant piece of my own family’s history. It is also, of course, an important piece of American social, political, and cultural history. I thought that it was important to make work about this particular moment in its ongoing history and evolution. The Harlem Redux work began in 2014 and is continuing. The current photographs that I am making–like Harlem Redux–are not portraits and are not representations of the human subject. I actually haven’t done a project that would be considered portraits since The Birmingham Project in 2012. Harlem Redux, and the Underground Railroad works, Night Coming Tenderly, Black are about the narrative of place and history, a reimagining of the past in the contemporary moment. Spending several year in Birmingham, Alabama researching and making work there has gotten me much more interested in history, and how that history in relation to African American experience might be visualized and reimagined.

“Portrait Of Barack Obama,” 2007 Commissioned By The Museum Of Contemporary Photography. © Dawoud Bey

As obvious as this might sound, I was incredibly moved by seeing your portrait of President Obama in the Whitney Biennial a few years ago. Can you tell me a bit about your experience making his portrait? I understand it was made in 2007, just before he announced his run for presidency.

Once I moved to Chicago and moved to Hyde Park, the Obamas were neighbors, living just around the corner from me. We also have close mutual friends, so I used to see them socially periodically. The Museum of Contemporary Photography wanted to commission me in 2007 to make a portrait of “a significant Chicagoan.” Barack Obama’s political star had started to rise at that time, and all of us who knew him had always considered him a “significant Chicagoan.” By the time I made the portrait they had moved, but were still in the same neighborhood. The tight security that followed his announcement for the presidential run hadn’t happened yet, so I got in touch with Michelle Obama to find out what his schedule was and when he’d be home. As a senator he was spending significant time in Washington, DC but came home periodically. On the appointed day, after taking his daughters to their tennis lesson, I went to their house with my assistant and I set up and made the portrait. In all honesty it was no different from how I had made other portraits; I always try to describe some aspect of the subject’s interior makeup. It was the same with the future president.

From “Harlem, U.S.A.” (1975-1979) © Dawoud Bey

From “Harlem Redux” (2014-2017) © Dawoud Bey

Have you thought of rephotographing him?

The selfies that I make of my (mostly) artist friends are a kind of social media project and a way of documenting our collective history. I have been asked if I would think of publishing them, but don’t intend to. They are entirely separate from the more intentional and “serious” work that I do, though an important kind of self-documentation that exists largely in the space of social media. I’d say there’s not a relationship between them other than that they are made with a camera.

Congrats on the MacArthur Genius Grant! What are you plans from here?

For the moment I am going to continue working on the Underground Railroad work in Cleveland, OH. This work will open in July, 2018 as part of the Front International Triennial in Cleveland. These are photographs and also a two channel video work. The photographs are large scale black and white night landscapes meant to evoke the movements of escaping slaves through the Cleveland landscape under cover of darkness. They are very different kinds of photographs for me, and contain no people at all. A few of the Harlem Redux photographs are populated, but those too are about looking closely at place, and how certain forces are impacting the transformation of place, of the physical and social landscape. I am continuing the Harlem Redux project even I am also continuing the work in Cleveland. The MacArthur Fellowship will allow me to continue to focus on the work at hand, and to perhaps accelerate the rate at which I’m able to achieve the work by having more time to devote solely to it. I spent the past seven months working on a massive monograph on my work that will be published in Fall 2018 by the University of Texas Press. The book Dawoud Bey: Seeing Deeply, Photographs 1975 -2017 will contain large selections of all of my photographic works from “Harlem, U.S.A.” up to the current Harlem Redux. It will also include an illustrated Chronology that contains a lot of visual history about the community that I came up in in the 1970s and 80s in New York. That community includes artists such as David Hammons, Mel Edwards, Ana Mendieta, Charles Burwell, Howardena Pindell, and other artists. That’s probably another reason I refer to myself as an artist, since most of the friends I came up with were artists of one kind or another, including poets and dancers, and not only photographers. We were all artists…period.