THE HOLE IS A MARK

McDowell’s selection of images is specific and intentional, as are his juxtapositions and rhythmic layout. His interpretation of this small sliver of the FSA imagery is entirely subjective and, as he writes, “does not represent the scope of the FSA photographic record. It is non-comprehensive in the photographers chosen, the breadth of their subject matter, and the geographic locations in which they worked.”

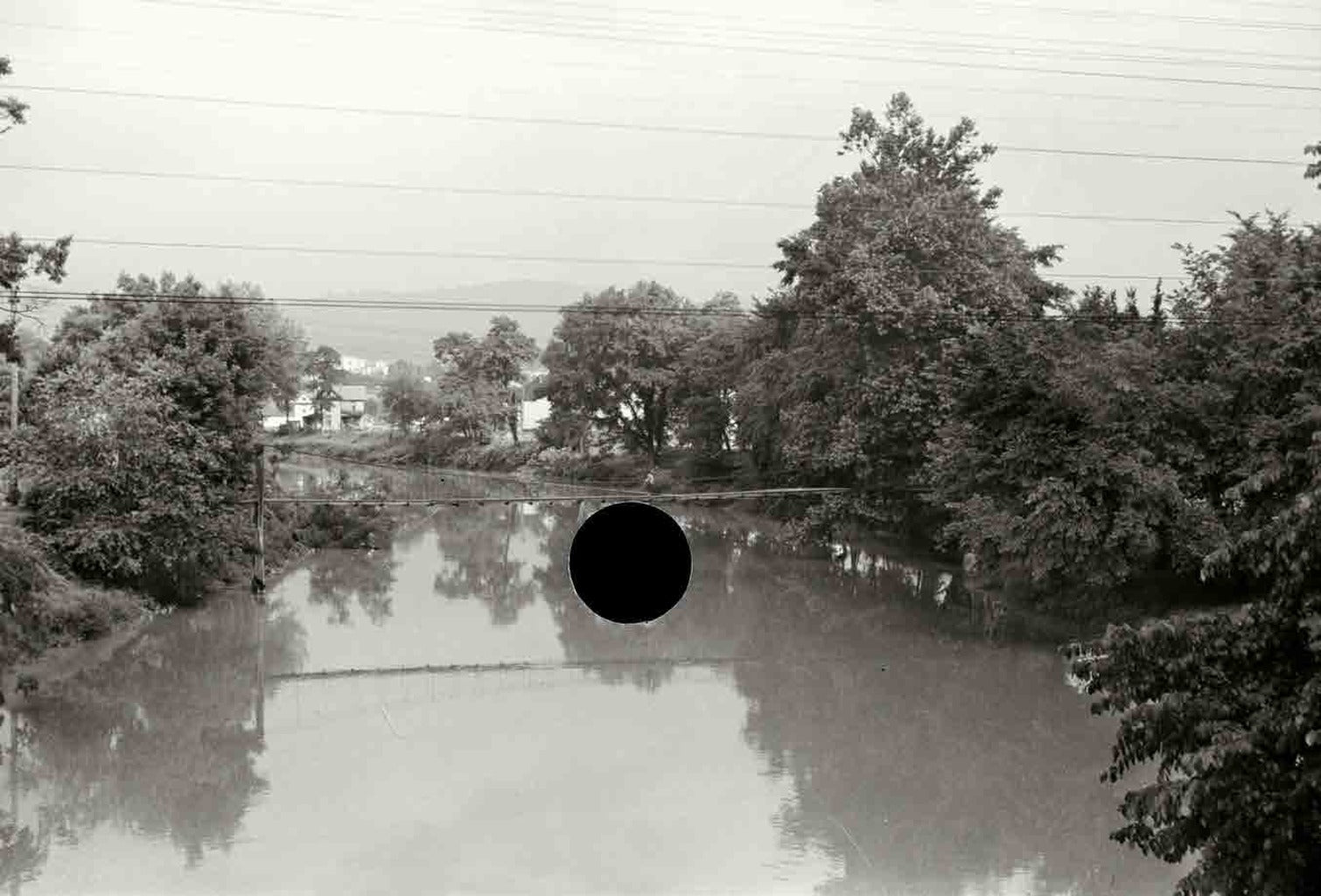

Untitled. Virgina. 1935. Arthur Ruthstein.

Mr. Tronson, farmer near Wheelock, North Dakota. 1937. Russell Lee.

Good farming land, Garrett County, Maryland. 1935. Theodor Jung.

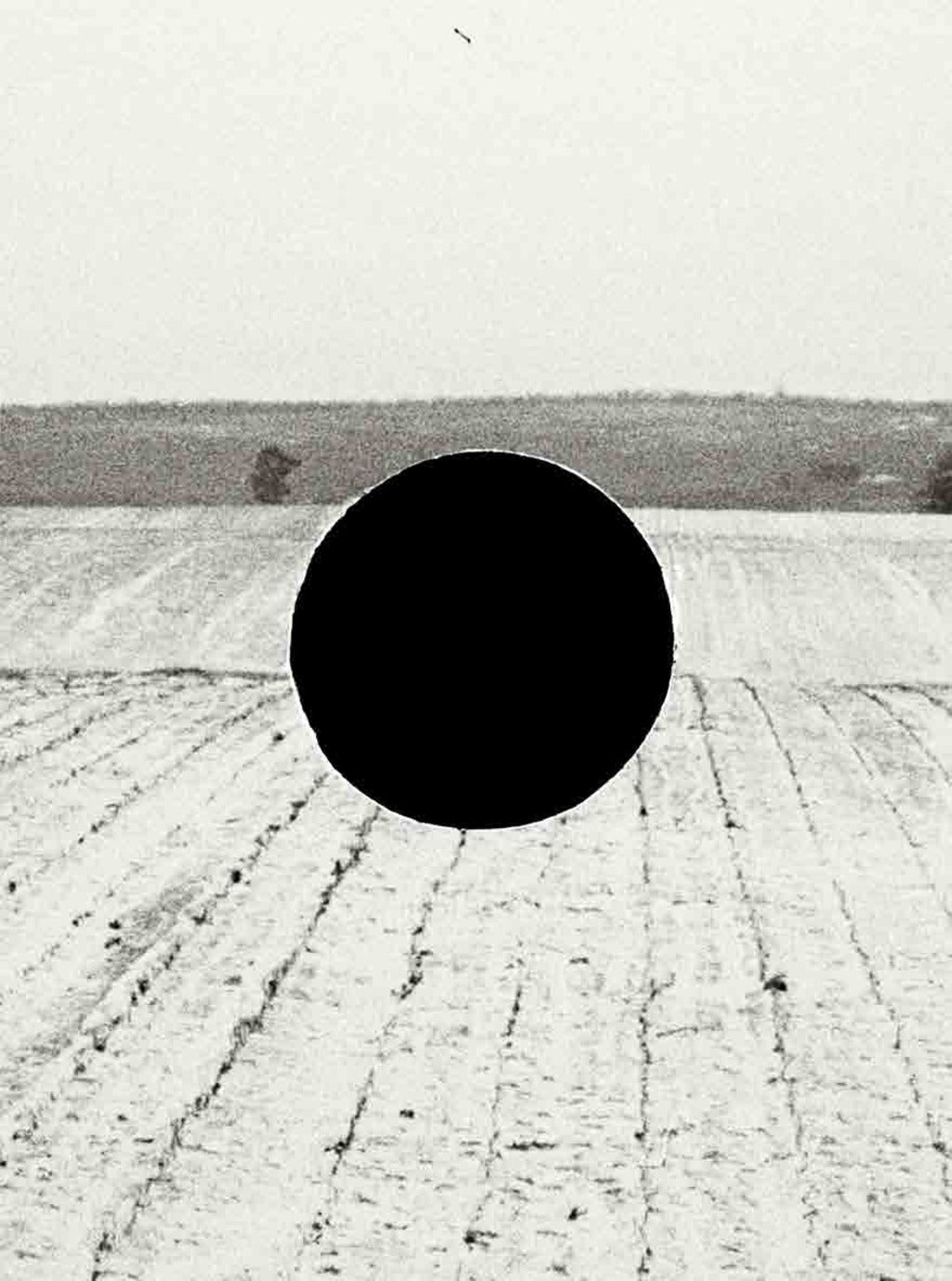

"Stryker unwittingly created a new picture, one that belonged neither to the mission of the photographer [nor to that of] the FSA.”

DJ Hellerman: How did you first discover the killed negatives?

Bill McDowell: I had a very powerful, almost visceral reaction the first time I saw a killed negative printed. It was in a magazine that accompanied a short article on the publication of Michael Lesy’s book Long Time Coming, published in 2002. I recall the image in the magazine was of a street scene, and it had a perfect black hole deleting part of the photograph. My reaction was something like, “Damn, I wish I had made that.” Looking back, it’s a little odd, because Lesy’s book, while about FSA photography, doesn’t include any killed negative images, although he briefly mentions them.

Untitled. Maryland. 1935. Theodor Jung.

Jewish poultry cooperative. Liberty, New York. 1936. Paul Carter.

BM: That’s correct - there is a dual meaning to the title. But I’m not sure that the reference to the various figure/ground shifts that occur in these photographs relates to my interest in formalism. Rather, I’m often drawn to photographs (or photographic situations) that have a certain pictorial intensity to them, and I use that as an entry point. And then it becomes a matter of how to work with and against that entry point to engage in more complex and nuanced relationships.

Getting fields ready for spring planting, North Carolina. 1936. Carl Mydans.

Untitled. Tennessee. 1936. Carl Mydans.

Bad road, Garrett County, Maryland. 1935. Theodor Jung.

“The simple presence of the hole joined the images together.”

BM: Yes. And one that relates pretty closely in its sensibility to other projects in which I was the artist making the photographs. In all of my photographic work I spend inordinate amounts of time in the editing process, testing relationships between images and layering meaning. What made Ground different for me was that because I didn’t make the original images, I had a built-in emotional distance to them that aided somewhat in building a structure where they would interact.

Blackjack oak, Withlacoochee land use project, Florida. 1937. Arthur Ruthstein.