UNMASKING YELLOW PERIL: THE PANDEMIC

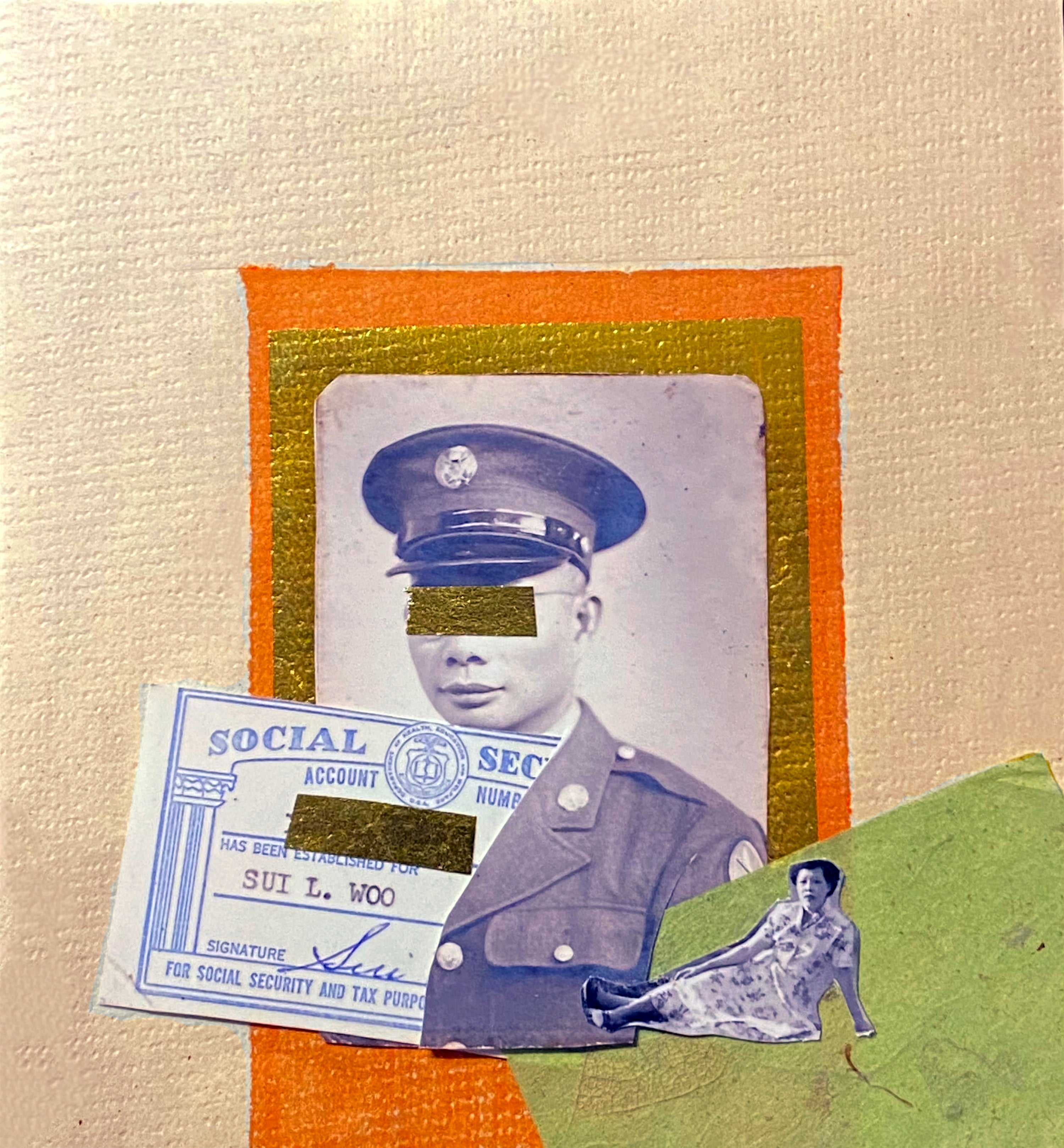

The wave of racial justice uprisings in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by police and in the face of anti-Asian violence sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic were a pivotal turning point for many. The pandemic revealed how racist attitudes towards Asians haven’t changed much. Today’s pandemic-related anti-Asian racism is deeply rooted in the “yellow peril” trope from 150 years ago— language that cast Asians as “perpetual foreigners.” Today, we are tokenized as the “model minority.” This structural racism is rooted in anti-Blackness. As a longtime activist and avid student of history, I know that we have to actively resist the white- washing of our narratives and challenge divisive “ascension to whiteness” and “model minority” frameworks.

How do these shared histories of living under white supremacy and oppression shape our present and future? As we imagine our liberated futures, how do we create a shared narrative that reveals parallel experiences, common threads of xenophobia, and stories of resilience that are inextricably tied to this country’s history of institutionalized racism, nativism, and colonialism?

My cultural collective, the Chinatown Art Brigade, has been joining forces with others in the community to fight the construction of the tallest jail in the world, in the heart of Chinatown. As cultural organizers who identify as abolitionists, we know we have to start with political education. How do we both acknowledge people’s lived experiences while challenging the roots of anti-Black- ness and structural racism? We begin by asking questions. How do we explain abolition and transformative justice to our elders, our parents, our children, and the working-class immigrants who live and work in our neighborhoods? How do we understand the economic forces that are threatening to displace our neighbors? How can we imagine a safer and more just world? How can we do this while joining abolitionist struggles that oppose increased policing and the construction of new jails?

In Asian communities, the term “abolition” can feel distant and even scary to some. Some are misguided by the Chinatown elite’s calls for more police to tackle anti-Asian violence and not-in- my-backyard (NIMBY) ideology. Layers of internalized racism and anti-Blackness must be unpacked. Our popular education and cultural-organizing approaches must meet people where they are, with care and concern, while putting forward a vision of collective liberation that rejects the carceral state.

Excerpt from a conversation that took place as a teach-in entitled “Envisioning Abolition in Our Local Asian American Communities,” organized by the Chinatown Art Brigade in partnership with Creative Time as part of Rashid Johnson’s Red Stage on June 9, 2021

Betty Yu: We are an intergenerational collective driven by the fundamental belief that our cultural, material, and aesthetic modes of production have the power to advance social change, racial justice, and economic justice. We are Asian American and Asian-diasporic-identifying artists, video makers, writers, educators, scholars, and activists who have deep roots in Manhattan’s Chinatown and the Chinatowns throughout New York City. Together we make work that centers art and culture as a way to support community-led organizing against gentrification, displacement, and racialized capitalism. Gentrification and mass displacement are inextricably tied and part of the same system of the prison-industrial complex that incarcerates and criminalizes and perpetuates state-sanctioned violence against our communities of color.

Linda Lu: This event was inspired by the protests of this past summer in response to the most recent spate of police murders of Black people and the more public dialogue around abolition and defunding the police that followed; the rise in violent public attacks on Asian Americans; the shooting and targeting of massage parlors and vulnerable Asian migrant women workers in Georgia; and, here in the city, the carceral response to these events in the form of the NYPD Asian Hate Crimes Task Force. That the first national conversations on race and racist violence that took place after the events and uprisings of the summer were centered on “Stop Asian Hate Crimes,” which is a criminal-justice framework that’s centered on the individual perpetrator, and which sets up the expansion of the prison-industrial complex, is consistent with how Asian Americans have historically been used as a wedge between white hegemonic power and racialized groups, particularly Black and brown folks. And it’s also not an accurate depiction or understanding of how racist violence actually shows up in our own communities, stratified by class, gender, immigration status, language, and the histories of the places and how people come here. We’re holding this event in order to center histories of Asian American organizing and racial-justice work that have been made possible by and which contribute to the rich histories of abolitionist organizing against the racist capitalist settler state that is the US.

LL: Our understanding of abolition is informed by the Black radical tradition and generations of Black freedom fighters who have articulated abolition as a political vision and a practice that demands the abolition of all forms of policing and police because it understands that policing itself is the problem. So, abolition means the fundamental redefinition of ideas of safety and of justice away from the police, the law, and the courts as a way of dealing with our social, economic, political, and interpersonal problems. Meaning that the entire foundation of our political order, which is built on anti-Blackness, settler colonialism, and racial capitalism, must be fundamentally rethought and dismantled.

Betty Yu: I wanted to say a little bit more about why abolition and why are we talking about this within the context of Asian American communities. A lot of Asian groups have been calling for more police presence, which we’re absolutely opposed to because it criminalizes folks of color and it pits us against each other. But also, as a working-class kid who grew up in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, with garment-worker parents, I often think about how I talk to folks like my parents, folks of their generation who are in their 70s and 80s. How do we actually see folks where they’re at and not use these sorts of words like, you know, abolition or white supremacy? Like, what does that actually mean? How do we talk to people about that? Folks in our communities, monolingual immigrants, Chinese-speaking or Korean-speaking, South Asian–speaking, monolingual immigrants? How do we actually have these conversations with them? And I think that’s also where the impetus for this teach-in comes from, and that the carceral state is part of the same system of labor exploitation, gentrification, you know, the system of incarceration, all these things are really tied together.

Frameworks oriented around “futurisms,” “reimagining,” and “re-envisioning” can feel removed from people’s everyday lived material conditions. Many of us are ready for a different system, ready to reimagine a different kind of society that is more just—that upholds racial, economic justice, immigration, health care, housing, and environmental justice. Radical imagination is critical at this historic juncture, because when we give ourselves permission to dream, to reimagine and unleash our visions of emancipatory futures, we make strides toward realizing it.

Read the entierty of Betty Yu's Essay in Familily Amnesia

Betty Yu

Betty Yu is an award-winning filmmaker, socially engaged multimedia artist, photographer and activist born and raised in NYC. Yu integrates documentary film, installation, new media platforms, and community-infused approaches into her practice. Betty’s films and multimedia work has focused on labor, immigration, gentrification, abolition, racism, militarism, transgender equality among other issues.