When Barney Kulok was in the sixth grade, he built a Rube Goldberg machine for his science fair project; a curving cardboard track the width of a golf ball that he tethered to a 35mm point-and-shoot camera. He would drop a golf ball in at the top, and at the bottom of the track the ball fell through a hole onto the camera, triggering the shutter. His intention was to capture the onlookers’ bewilderment, but because of the camera’s off kilter positioning, he ended up with a roll of photos of the onlookers’ crotches. “I think this was the beginning of my interest in elaborate picture-making devices,” Kulok says. While he didn’t pursue another project again until late in high school, Kulok’s pursuit of photography’s controlled mechanical possibilities and its ability to record the unexpected and reinterpret common visual assumptions would imprint themselves into his practice years later. For the past ten years his work, which ranges from quiet urban landscapes and video installations to meditations on architecture and digital interference, is linked by a tendency to see the world outside as a terrain that breaks from our commonly held visual assumptions - an open studio with limitless possibilities.

© Barney Kulok from Building

Kulok first approached photography in a dedicated capacity when he was a senior in high school, after his mother gave him Irving Penn’s 1960 book Moments Preserved: Eight Essays in Photographs and Words. “I had never seen anything like it,” he says, “when I put that book down I decided to be a photographer.” A few weeks later, with limited technical experience and fresh drive to make pictures, he began working intermittently as an assistant for Timothy Greenfield Sanders, who taught him the basics of studio lighting and gave him a Rollieflex camera to encourage his new obsession. Kulok immediately set up a makeshift portrait studio in his parent’s living room in Manhattan, photographing “anyone who would sit for me,” and by the end of the year he had his first exhibition in the school lobby of portraits of all his classmates and teachers.

Once graduating, Kulok enrolled in the photography program at Bard College, studying with Stephen Shore, Larry Fink and Vik Muniz, and immersed himself in learning and absorbing the complexities of studio lighting and portraiture. “I had never taken a real photography class before I went to college, and Vik taught my first class my freshman year at Bard.” He says. “Over the course of that semester he made me rethink everything I thought I understood about photography.” Kulok’s initial projects at Bard were wrought with trial and error as he grappled with the technical complexities of making pictures in the studio. Perhaps channeling Paul Strand, during his sophomore year he worked on a short-lived series of portraits of people with Macular Degeneration, a condition of near-blindness that makes the world look as if it were severely fogged on all edges, as well as numerous other intermediary projects aimed at resolving the challenges of the studio. While this early work was nearly all portrait-based, it was a building block towards his next decade of work focusing on the poetic and psychological possibilities of a largely inanimate landscape.

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

While Kulok’s images seem discordant on the surface, they volley off each other to illustrate a precise, controlled way of looking, devoid of the pre-conceptions of their geography.

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

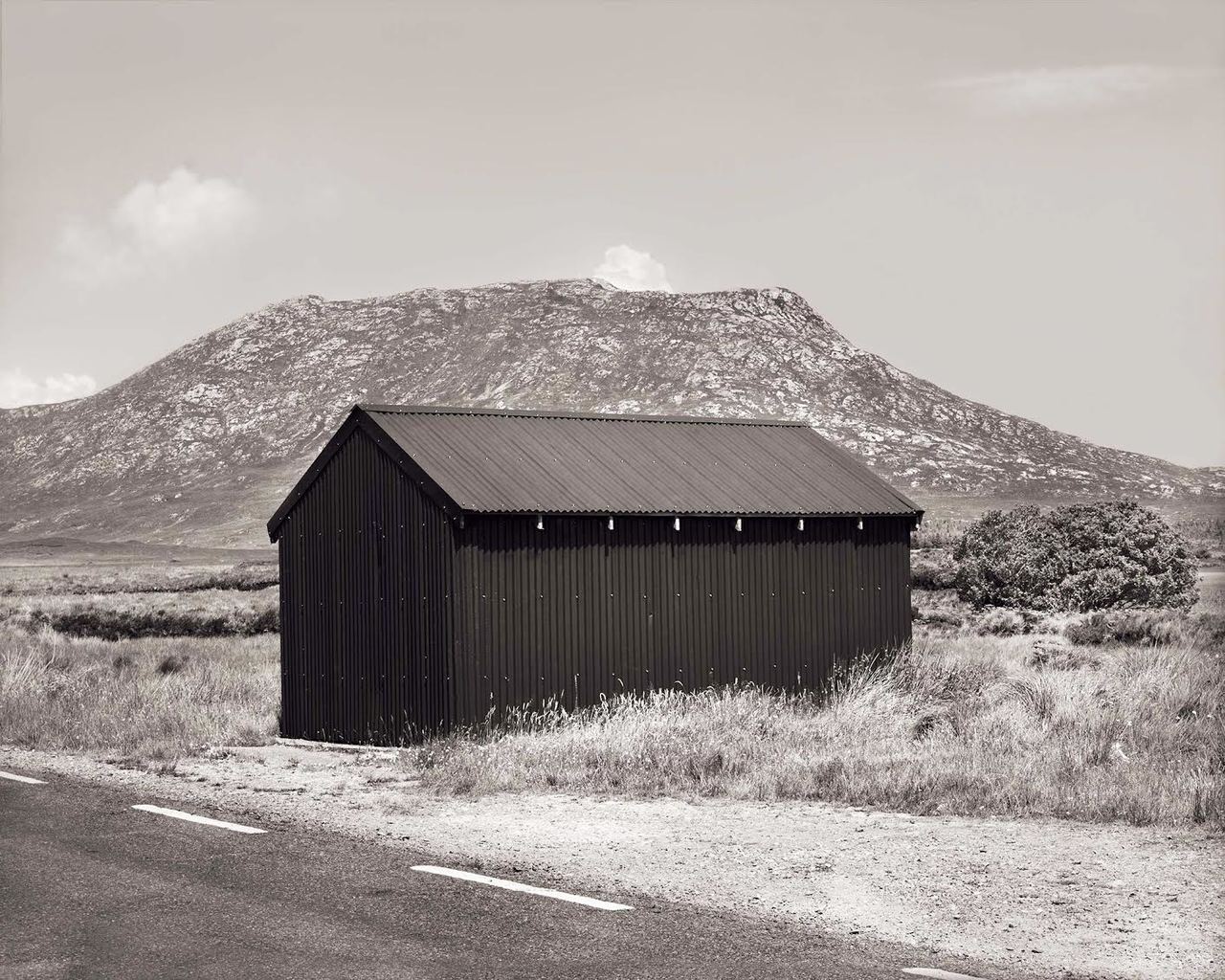

Near the end of his time at Bard, Kulok’s process developed from one based in the studio to one that in many ways used the studio as a metaphor for seeing and interpreting the world around him and would shape much of his artistic trajectory onward. In much of this work, including his 2005-2007 series Simple Facts, Kulok used what he learned at Bard to give new and uncharted vision to New York City’s often overly photographed landscape. A seemingly random mix of black + white and color images turn a potentially hackneyed tapestry of visual tourism into decontextualized visual notes. In one image, for example, a stained car seat headrest, lit by a soft, yet glowing ambient light consumes the frame. It has an unexpected pulse, a sense of breath despite its banality. When exhibited at Nicole Klagsbrun gallery in 2005, Kulok paired it with color images of inner city billboards, nightscapes which were printed as transparencies and exhibited on light boxes, a non-portrait closeup of Kulok’s father pulling a camera shutter - its flash exploding into precise geometrical streaks, a platinum print of a barn shot far from the city. While Kulok’s images seem discordant on the surface, they volley off each other to illustrate a precise, controlled way of looking, devoid of the pre-conceptions of their geography. Simple Facts was a study on vision and process of seeing, much like his undergraduate studio experiments.

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

© Barney Kulok from Simple Facts

Around the same time, Kulok worked with long time friend and filmmaker Sebastian Bear McClard to produce River of Shadows, a suite of twelve continuously looping videos. The videos used ambient light to transform commonplace exteriors of a neighborhood into a magically hued psychedelic palate. Gathering light emitted from a large LED billboard screen in the industrial part of Long Island City, they depict the illuminated walls, streets, cars, and other surfaces in the neighborhood below. While their compositions are static, they pulse with the animated, constantly changing color of the advertisements. “At the time we were making the videos I was also making photographs at night in and around Long Island City, using available artificial light.” Says Kulok. “The video installation came out of the conversations Sebastian and I were having - they were an attempt to try to carve out a space between the film and photography.” The title of the installation was borrowed from the book of the same name about Eadweard Muybridge and his importance as the bridge between photography and cinema.

© Barney Kulok and Sebastian Bear McClard from River of Shadows

BIG WINDOW from River of Shadows on Vimeo.

As Kulok continued to consider photography’s expanded ability to transcend landscapes and objects beyond their commonly held associations, he began experimenting with paint and other traditionally “non-photographic” materials. This surfaced in a series of four large-scale spray-painted, stenciled panels and one photograph. The series In Visible Cities, was exhibited at NYC’s Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in 2009. To make these pictures, Kulok selected two points in Manhattan, which would serve as the panels’ frame, choosing the locations for places that once existed at these coordinates but had since disappeared (Minton’s Playhouse, Max’s Kansas City, the gunshop made famous by photographers Weegee and Berenice Abbott). He walked between these sites and collected the names of all the WiFi networks that appeared on the screen of his phone along the way, arranging the found text from each walk into grids from which he produced large stencils. Phrases like “PrettyBoy olive in the city GEORGE flywithme sugarbush The Swamp mrsmoustache” overwhelm and fade into each four by eight foot panel recording and preserving them like the disappearing places they temporarily represent.

“I’ve often thought about what a photographer would do if the thing that they wanted to photograph was invisible. How could I apply the principles of photography to depict an invisible landscape?”

For Kulok, despite being made without a camera, these recordings are still conceptually photographic in their rendering of place and the passage of time in the city. “I’ve often thought about what a photographer would do if the thing that they wanted to photograph was invisible.” He says. “How could I apply the principles of photography to depict an invisible landscape?” Like his earlier representations of the city, these images are poetic abstractions that highlight the invisible and overlooked structures behind his experience of living there. Invisible Cities concludes with one actual photograph, an image of the paintings detritus left on the Kulok’s studio wall behind the last panel he created. For Kulok, the process of making these images, resulted in something he could photograph. “It was as if I had to do the whole project just to get to that image.” He says. “This image was a bridge back to photography.”

© Barney Kulok from Invisible Cities

Kulok’s unconventional eye, hovering between abstraction, documentation and representation continued in Building, his 2011-2012 series of black and white photographs of architect Louis Kahn’s FDR Memorial on Roosevelt Island. After viewing his son Nathaniel Kahn’s film My Architect in 2003, and traveling to see many of Kahn’s works throughout the United States in the following decade, Kulok learned of plans to build Four Freedoms Park on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, in NY, and wrote the builders asking to photograph its construction. While other photographers might straightforwardly document its architecture, Kulok’s work is a deeper meditation on light, form, and the psychology of space. “What moved me most, and what distinguishes Kahn from other architects,” says Kulok, “was the light. As a photographer it was easy to fall in love with Kahn’s buildings because the light is so active; he wanted the light to have a value equivalent to other building materials like stone, concrete or wood.”

“What moved me most, and what distinguishes Kahn from other architects was the light. As a photographer it was easy to fall in love with Kahn’s buildings because the light is so active; he wanted the light to have a value equivalent to other building materials like stone, concrete or wood.”

The photographs that transpired had little to do with the building, or even Kahn’s architectural philosophy, instead, like Simple Facts, they focused on the psychological implications of form and light. Brick, shadows, and multivariable gray tones elevate Kahn’s materials into something ethereal, much like his earlier headrest photograph from Simple Facts. “I wasn’t interested in making illustrative photographs of the design,” he says, “or making a narrative documentary project about the construction.” Despite the potential loaded possibilities of the space, Kulok’s unique eye turns a construction site into a temporary, metaphoric outdoor studio.

In Kulok’s most recent work, The Dusty Sensor, he extends his exploration into the photographic essence of landscape and object into the digital realm. The title of this ongoing series of pictures was spawned from his irritation towards the presence of dust on the sensor of his digital SLR camera. “When dust appears on the sensor of my camera I get very frustrated,” he says. “I don’t know how the hell it gets there, and it is very annoying to try to get it off. But I am interested in how those specks of dust behave as a kind of analog photographic interference, like little traces of the world forcing their way into the photograph.”

Since much of Kulok’s earlier work was made with a large format film camera, his recent transition to digital furthered his curiosity toward how the technology, and the presence of Photoshop, manifests itself in the non-digital world. In one image, Erased Door, for example, a door shaped patch of fading paint and stucco appears on the side of the building and occupies the center of the image; next to it, at the edge of the frame, a similarly sized red door mimics the shape of the missing door. Whether or not this existed in reality, its imprint references digital erasure and post-production techniques that viewers have come to expect in our everyday process of looking at the world and its photographic representations. Many of these images reference digital techniques, tropes, and failures, as they intrude into the ‘real’ world. Like Kulok’s earlier work, The Dusty Sensor drills into the essence of the material he photographs, exploring the signals of their forms pulled back from their cultural associations.

“I am interested in how those specks of dust behave as a form of analog photographic interference, like little traces of the world forcing their way into the photograph.”

When Joel Sternfeld, in his introduction to Barney Kulok’s 2005 lecture at Sarah Lawrence College, referred to him as a “Young Mozart,” he wasn’t being facetious. His trajectory over the past ten-plus years has been remarkably prolific, and his process of “seeing” and processing the world around him are some of the most aesthetically varied, yet conceptually consistent of his generation. For more than a decade, he’s made multiple elegant bodies of work, transforming quotidian and often overlooked details of his environment into quiet tone poems, using the world around him as a play-space with open unlimited possibility.

© Barney Kulok from The Dusty Sensor