Dancer (19)

I’ve always been curious. As a child, I loved anything that made me feel like a spy. My father, a pathologist, took my brother and me to his lab and let us look at slides through a microscope. I watched the world of things unseen appear, like universes to be interpreted and understood. My mother, an artist, had taught me how to take photographs. The act of capturing something on film cut through the noise and showed me something that I’d only been partially able to see.

It reminded me of sculpture, which my mother had also taught me about. The thing you could only see in a photograph was just like the figure hidden in stone before it was chipped away, the thing that was there the whole time, even if only the artist knew it. I realized then that I could use art to better make sense of the world around me. Photographs could capture the clues I needed to create change.

Guide (70s)

Embellished (50s)

This body of work is my call to action. A response to the spoken and unspoken

messages women receive around their bodies, their self-worth, and the responsibility to be beautiful. I saw that our moods, activities, and relationships with others and ourselves were being impacted by this phenomenon. This was a response to questions I’d been ruminating on for some time.…

What is my body even supposed to look like? Why do women feel the responsibility to try to be beautiful in the first place? Why can’t we shift the conversation away from being beautiful toward what is meaningful and purposeful about our bodies?

Guide (70s)

Believer (30s)

By the time I was in my 20s, I knew this was something I wanted to explore further. To document. I saw that women of all ages and shapes were often alarmingly critical of their bodies. My relationship with my own body was complicated. At the time, I was getting a BFA in acting from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and was auditioning for plays and commercials. I began to feel alienated and hyper-focused on the emphasis on physical perfection in the acting world, and at times I felt like I was part of the problem, buying into the idea that there was one ideal body type.

I wanted to know what I was supposed to look like by exploring reality, not only from the lens of the beauty and health industries or from the media. I wanted to know what women looked like naked as they aged. I wanted to photograph as many women as I could, but it felt daunting. I wasn’t sure I was ready for what I would discover.

Squish

Honeybee (30s)

A decade later, three kids had transformed my body, turning it into something unfamiliar. I had known that my body would change and that it had the right to change, and yet I was also deeply aware of an expectation that I was supposed to leave the hospital fitting into my old clothes. It seemed that my body wasn’t valued in this state, even though I had just created a life. I was changed.

At this time, I was ready for my project emotionally, but I was busy enjoying my young children and my work: photographing portraits of actors, musicians, and families. The timing was off. It wasn’t until age 40 that I would finally pick up my camera and begin the task of finding out what the rest of us look like if we are lucky enough to live into our 90s, after our mastectomies, the day before we give birth and the years after, when we are senior citizen–age athletes, when we have had surgeries, when we fight for our lives, and when we are at the end of life.

Hope and Despair

New Yorker (40s)

In New York and Miami I photographed waitresses, famous actresses, physicians, politicians, journalists, activists, mothers, cancer survivors, incest survivors, rape survivors, women without jobs, cashiers, lawyers, researchers, writers, trans women, queer women, heterosexuals, lesbians, women from an array of religious beliefs and devoutness, agnostics, and atheists, as well as people of different races and nationalities. By no means was it a comprehensive representation of us all, but it was a start.

Some women undressed while they were signing the contract and seemed to be completely at ease. Others spent 45 minutes in the bathroom and only came out reluctantly. One let her sarong fall and began to sob. I’d already learned to be quiet and not rush in to fix the situation. When she was done she told me that she was 75 years old and that she had never felt so in her body—so comfortable and empowered— as she did in that moment.

Poet

Volunteer (80s)

The skills I learned at NYU while acquiring my Master of Social Work came into play in new ways, leading to a comfortable dynamic with the women I photographed and an easy exploration of very complex and private questions. Most women shared their stories and feelings about their bodies as I was photographing them.

I heard about work, love, sexuality, self-hatred, illness, family, addiction, gender identity, transgender journeys, love affairs, self-abuse, childbirth, infertility treatments, diets, exercise regimens, failures, successes. The majority of women shared their “Me Too” stories. Ultimately the project allowed me to be a spy on humanity in a way I could never have imagined.

I heard about work, love, sexuality, self-hatred, illness, family, addiction, gender identity, transgender journeys, love affairs, self-abuse, childbirth, infertility treatments, diets, exercise regimens, failures, successes. The majority of women shared their “Me Too” stories. Ultimately the project allowed me to be a spy on humanity in a way I could never have imagined.

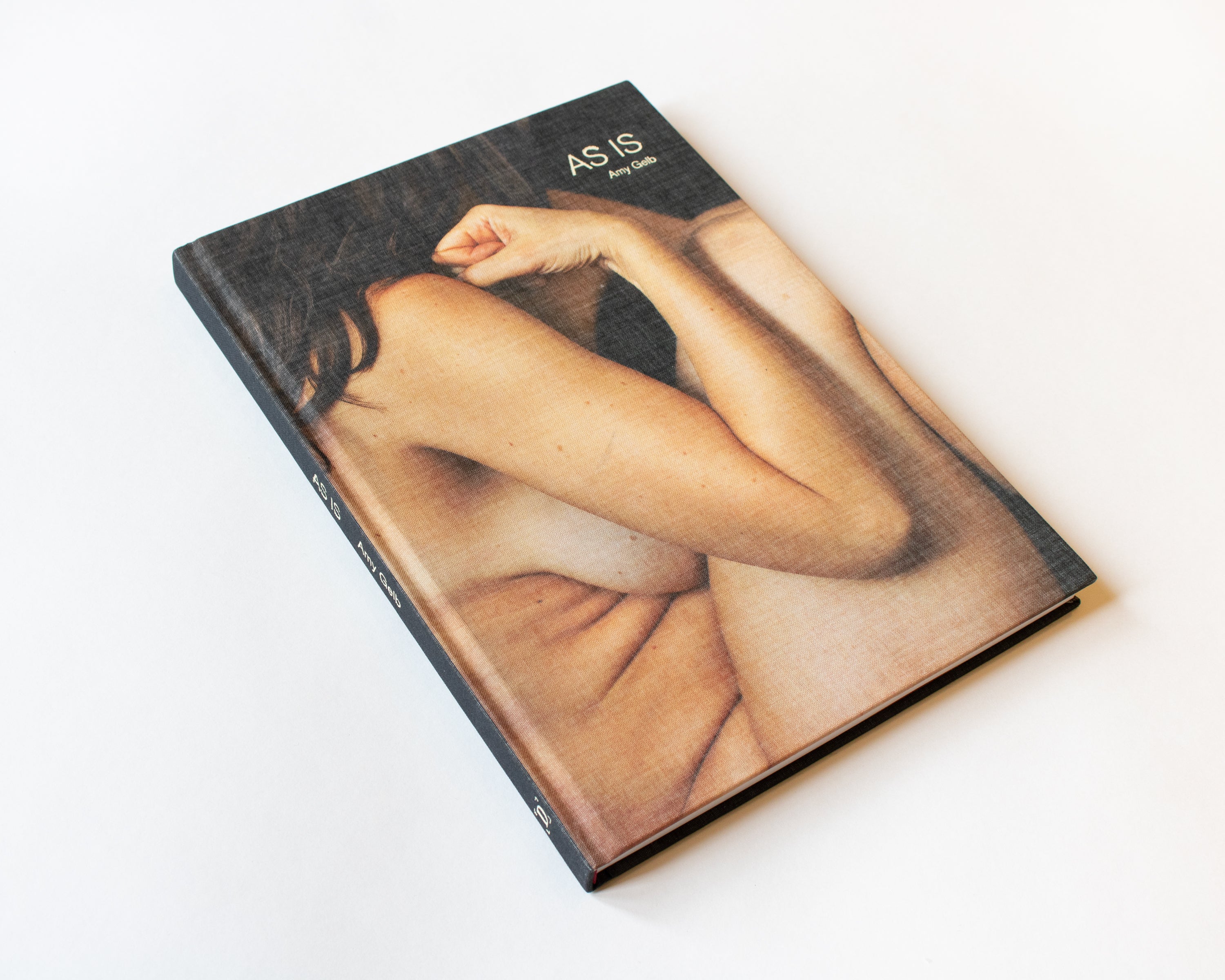

Read the full essay in Amy Gelb’s new book, As Is: Women Exposed.

Read the full essay in Amy Gelb’s new book, As Is: Women Exposed.