Giving is Living

Essay by Richard Harris

It’s been nearly thirty years, and for me, it’s a moment frozen in time. Thumbing through my hometown newspaper, the Boston Globe, in the Washington bureau of ABC News, a headline in the Living section jumped off the page: “A Professor’s Final Course: His Own Death.” What I couldn’t have known at that time is that the virtually unknown man being profiled would soon become increasingly famous in this country and then globally—almost a household name—especially in the years after he left us.

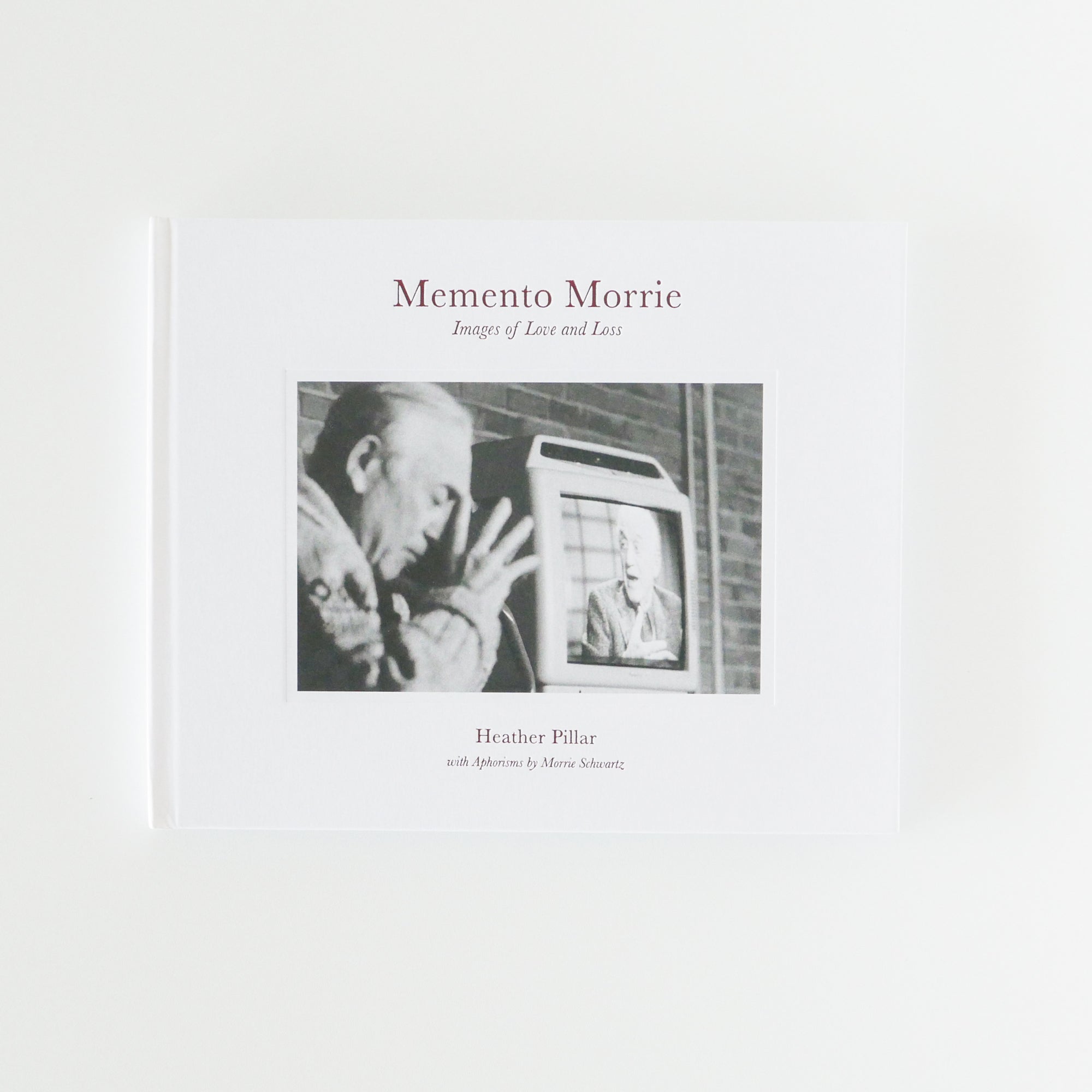

It was March 1995 when the secret of this elfin man was first revealed to the outside world. Brandeis colleague and friend Maury Stein had sent the Globe some of Morrie’s aphorisms about how to live your life in a world where no one gets out alive. The Globe feature appeared seven months after Morrie was diagnosed with ALS, and eight months before he died, but it was clear that Morrie didn’t fit the stereotype of someone facing a fatal diagnosis. Stein described his friend by remarking, “unlike most people terminally ill who retire into the woodwork, he [Morrie] has blossomed,” something Heather captured beautifully during Morrie’s final months. Heather’s images of a steady stream of well-wishers visiting their ailing friend underscored Morrie’s belief that you can still find meaning in life while terminally ill.

In a culture where death remains largely in the shadows, talked about in whispers, Morrie Schwartz, ever the teacher, didn’t withdraw but turned his impending death into an ongoing class to anyone who’d listen. He’d invite friends, colleagues, students—young and old alike—to his home to “learn what they can about the grand mystery—death,” as the late Globe writer Jack Thomas put it. Even if you don’t subscribe to the “things happen for a reason” view of life, the cascade of events touched off by that March 1995 Globe story may change your mind. As senior producer of Nightline at the time, and after reading about Morrie in the Globe, I recalled a conversation I had with anchor Ted Koppel not long before. He mentioned that when he was growing up in England, the topic of death was hardly hidden; that people didn’t fear it the way they seemed to in the United States. Ted wanted to devote a Nightline episode to how different cultures ponder death, but he couldn’t find a way into the story.

So I shared the Morrie story with Ted, suggesting we devote a Nightline episode to that rare, dying man who was eager to bring death out of the shadows into the light. Ted quickly asked me to reach out to Morrie and see if he’d be interested in talking with him. When I got Morrie on the phone, it was clear he was not much of a television watcher. He barely knew of Nightline or Ted Koppel, but was willing to do the show on one condition: that he could interview Ted first.

Not television savvy, Morrie didn’t see Ted so much as a television celebrity but as another person to help spread his message to a national audience. They bonded quickly and had a good chemistry. Morrie told Ted he seemed like a “narcissist” and Ted’s retort was “I’m too ugly to be a narcissist.” They laughed and began a close friendship, where Ted interviewed Morrie three times over the next eight months. As ALS ravaged his body, Morrie wanted to demystify the one universal experience that awaits us after we’re born: death. But there was something more. As Morrie told Ted, “When I’m dying, I don’t only have to be taking, I can be giving ... and that’s unusual for a dying person.”

So Morrie took his lessons on living, which he discussed with various groups at his home, to a national TV audience. And when the first of three Nightline interviews with Morrie aired one Friday night in March, one of Morrie’s favorite students, Mitch Albom, stumbled on it while channel surfing in Detroit and was shocked to discover that his mentor was dying. Just sixteen years earlier at his graduation from Brandeis, Albom had promised Morrie, his favorite professor, that he’d stay in touch. Instead, Albom would become a workaholic sportswriter and put Morrie in the rearview mirror.

But after the upsetting news about his old professor, Albom made it up to Morrie in ways that can’t be fully calculated, visiting him for fourteen Tuesdays, interviewing him to write a slim volume to help pay for his medical expenses. Publisher after publisher rejected the manuscript, but just before Morrie died Mitch was able to give him the good news that the book had a publisher. Morrie would never read the book. But over nearly three decades, many, many have. Tuesdays with Morrie would become one of the highest-selling memoirs in the history of publishing and assure that Morrie Schwartz would continue to get his life lessons out to the world.

Read the entierty of Richard Harris' essay in Heather Pillar's Momento Morrie: Images of Love and Loss

Heather Pillar

Heather Pillar, photographer and teacher, has lived, taught and photographed in seven countries over four continents during the past 25 years. Her personal and collaborative photographic projects reveal her ongoing interest in women, girls, education and aging.

Richard Harris

Richard Harris is an award-winning television, radio, print, digital, and film journalist Harris is a consultant to the nonprofit iCivics, former producer of NPR’s All Things Considered, and former senior producer of ABC News’s Nightline with Ted Koppel.